A popular show business axiom insists that "Dying is easy, comedy is hard." While any performer who has bombed onstage will quickly acknowledge this bitter truth, the bottom line is that comedy depends on good ideas and solid execution. Mary Elizabeth Williams makes this point brilliantly in her article for Salon.com entitled

Stephen Colbert is Dead, Long Live Stephen Colbert!

During one recent week I attended performances of three very different comedies.

- One was a world premiere, the other two were Bay area premieres.

- All three shows were solidly cast with tightly-knit ensembles that employed strongly talented performers.

- Two productions sizzled, challenging their audiences with issues critical to their lives while causing them to repeatedly laugh out loud (proving beyond any doubt that just a spoonful of sarcasm helps the medicine go down). Curiously, these two plays delivered a wealth of information to their audiences which reflected each creative team's personal passions.

- The third, quite surprisingly, fizzled out. Audience response was polite, but noticeably tepid.

- What could have caused such a difference in response? Was it just a sober audience on a weekday night? Or were other, more subtle factors at play?

* * * * * * * * * *

Suppose you want to write a play that tackles a difficult and extremely newsworthy issue. How can you position it dramatically in an easily understandable setting for a contemporary audience? In the following video, Tony Taccone explains how he and Dan Hoyle teamed up to write

Game On for the San Jose Repertory Theatre.

Written for a cast of five (who perform on a unit set), the protagonists of

Game On are two impassioned losers whose fanatic devotion to fantasy baseball helps to distract them from the sadder and more distressing realities of their lives.

- Vinnie (Marco Barricelli) is a middle-aged, Brooklyn-born Italian-American facing some steep medical expenses. When he is not driving a cab in and around San Francisco, the frequently depressed Vinnie is glued to his television, watching documentaries about endangered species on the Discovery Channel. A sensitive soul whose emotions are easily manipulated by mass media, the sentimental, anthropomorphically-vulnerable lug has taken to giving individual polar bears names like "Petie" because he feels so deeply about the perils they face as a result of climate change.

- Alvin (Craig Marker) is a cold and clinical numbers man. In contrast to Vinnie (who always goes with his gut), Alvin has been using sabermetrics as a tool for building his fantasy baseball team (as well as building statistical arguments for the entrepreneurial dream he and Vinnie share to make insects a new and extremely profitable source of animal protein for the American diet). If all goes well, a culinary trend embracing entomophagy could make them incredibly wealthy.

![2014-05-09-GameOn1.jpg]()

Craig Marker and Marco Barricelli in Game On

(Photo by: Kevin Berne)

In a way, Vinnie and Alvin are not that different from Max Bialystock and Leopold Bloom in

The Producers . Both are small-time idealists who are completely out of their league trying to raise money to support their dreams. If only someone with megabucks to spare would taste some of Vinnie's fresh, worm-laden spring rolls or fried crickets, Vinnie is sure that the dipping sauce alone could convince that person to write a check!

As the play opens, Alvin and Vinnie are in the television room of an upscale home in Los Altos, which is close to Silicon Valley's deep pool of venture capital. As they eagerly await some precious face time with a Godot-like mogul (who has an expressed interest in "green" projects), they argue about baseball players and fundraising strategies. It soon becomes obvious that, while Vinnie is a man of deep passions, Alvin is a rabid control freak.

![2014-05-09-GameOn2.jpg]()

Craig Marker and Marco Barricelli in Game On

(Photo by: Kevin Berne)

The hard truth is that neither Alvin nor Vinnie is equipped to go swimming with the venture capital sharks of Silicon Valley. Alvin, in particular, is so wrapped up in numbers and the "rules of the game" that he misses important body language cues and important "tells" dropped by those who step into the game room. They include:

- Bob (Mike Ryan), a Silicon Valley entrepreneur whose company has just been bought by the Godot-like mogul and who is now scouting potential business acquisitions for his new boss.

- Glen (Cassidy Brown), Alvin's former fraternity brother who, following his recent divorce has quietly "married up." A bit of a doofus, Glen plans to don a cape and ski mask and use a bullhorn to intimidate the guests at his wife's party into making larger donations to green causes. His attempt to create and perform a politically confrontational rap song (most probably written by Dan Hoyle) is hilariously misguided.

- Beth (Nisi Sturgis) is Glen's new wife, a diehard sports fan as well as a wealthy Silicon Valley player who is hosting the party and knows the revered billionaire on a first-name basis. She's much better at getting people to write checks than Glen could ever hope to be.

![2014-05-09-GameOn3.jpg]()

Craig Marker, Cassidy Brown, and Marco Barricelli in Game On

(Photo by: Kevin Berne)

Hoyle and Taccone have fashioned a script which covers a lot of topical issues while delivering a steady supply of laughs to the audience. Their play is nicely structured, with plenty of unexpected twists and turns. Working on John Iacovelli's stylish unit set, Rick Lombardo has directed with a sure hand (San Jose Rep's impressive study guide for students attending performances of

Game On includes a wealth of material on such topics as global warming, food and sustainability, entomophagy, fantasy baseball, sabermetrics, how to fund a startup, and whether or not to seek venture capital).

While Craig Marker has developed a reputation for delivering solidly-crafted characterizations, Alvin's spectacular emotional meltdown allows him to show audiences what an impressively layered artist he can be with the right material.

Game On gives Marco Barricelli a much stronger opportunity to show his strengths than he received from A.C.T.'s recent production of Eduardo De Filippo's

Napoli.

In supporting roles, Mike Ryan offered an appropriately bland Bob while Cassidy Brown enjoyed some deliriously comic flame-outs as Glen. In her limited time onstage, Nisi Sturgis had no trouble communicating to the audience that Beth was much more shrewd and savvy than any of the men in

Game On.

* * * * * * * * * *

As in

Game On, the dialogue in

Wittenberg (which recently received its Bay area premiere at the Aurora Theatre Company in Berkeley) fairly crackles. That may well be because playwright David Davalos is also an actor. Davalos first got the idea for his play in 1991, while appearing as Rosenkrantz in a Utah Shakespeare Festival production of

Hamlet. As the playwright notes:

"The theatre I enjoy best as an audience member (Shakespeare, Shaw, Stoppard) also challenges and provokes me, be it emotionally or intellectually. To an Elizabethan audience, a reference to Wittenberg both identified a person there as Protestant and as someone immersed in an academic environment of intellectual foment and questioning -- as if an American Hamlet in the 1960s were identified as coming home from Berkeley or Kent State. In many respects, I reverse-engineered Hamlet's psychology from the moment in Hamlet when he's just about to stab a praying Claudius but second-guesses himself. I wanted to suggest that Hamlet's internal moral conflict pre-dated Hamlet."

![2014-05-09-wittenberg1.jpg]()

Jeremy Kahn as Hamlet in Wittenberg (Photo by: David Allen)

It's an interesting dramatic trick, made all the more accessible by Tom Stoppard's breakthrough success with 1966's

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. Billed as "A Tragical-Comical-Historical in Two Acts," Davalos's play (which premiered at the Arden Theatre Company in Philadelphia in 2008) takes place in October 1517 as Hamlet (Jeremy Kahn) is still struggling to decide whether to major in philosophy or theology (like some of his classmates, he's also been hanging out at the Bunghole Tavern).

Two of the university's most noteworthy professors, Dr. Faustus (Michael Stevenson) and Martin Luther (Dan Hiatt) are vying for the attention of the Danish prince who, as a senior, is due to graduate as part of Wittenberg's class of 1518. However, Hamlet recently spent a summer in Poland, where he was exposed to the dangerous astronomical theories of Nicolaus Kopernik claiming that the sun (rather than the earth) is the center of the universe.

![2014-05-09-wittenberg2.jpg]()

Dr. Faustus (Michael Stevenson) and Martin Luther (Dan Hiatt)

try to influence Prince Hamlet (Jeremy Kahn) in Wittenberg

(Photo by: David Allen)

Hamlet is under no great pressure to make up his mind. His ability to win at sports (due in large part to the referee's deference) allows him to enjoy his royal status on the tennis court as well as in the classroom. Ironically, Hamlet is not the only one facing some difficult decisions.

- Prone to scatological complaints, Martin Luther is battling a severe case of mental, physical and spiritual constipation that is miraculously eased by his colleague's insistence on the ingestion of coffee. The play begins several days prior to October 31, 1517 when, outraged by the Dominican friar Johann Tetzel's continued sales of indulgences as a fundraising tool, Luther launched the Protestant Reformation by nailing his revolutionary Ninety-Five Theses to the door of Wittenberg's All Saints' Church.

- After many years of debauchery, Dr. Faustus is actually thinking of proposing to his steady paramour.

- Helen (Elizabeth Carter) may have started off as a nun but, as one of Europe's most valued courtesans, has no intention of giving up her independence to accommodate her lover's neediness.

![2014-05-09-wittenberg3.jpg]()

Dr. Faustus (Michael Stevenson) and Helen (Elizabeth Carter)

congratulate Hamlet (Jeremy Kahn) on winning a tennis match

in Wittenberg (Photo by: David Allen)

There was so much to admire in the Aurora Theatre Company's production of

Wittenberg. From Eric Sinkkonen's intriguing unit set to Maggi Yule's handsome period costumes; from Josh Costello's clever stage direction to the work of his finely-tuned four-actor ensemble, this play glows with the kind of intelligence, wit, precognition, and mischievous cross-referencing that could give a puzzle fanatic like Stephen Sondheim an erection.

It's rare to leave a theatre thinking how much you'd like to get your hands on a copy of the script so that you could slowly savor all the puns, comedic setups, and insider jokes that Davalos has so intricately woven into

Wittenberg. While one doesn't need a thorough knowledge of

Hamlet, Dr. Faustus, or Martin Luther's life to enjoy this play, the stronger one's sense of history and literature, the more fun a person will have at any performance of

Wittenberg.

![2014-05-09-wittenberg44.jpg]()

Martin Luther (Dan Hiatt), Dr. Faustus (Michael Stevenson), and

Hamlet (Jeremy Kahn) are all severely conflicted in Wittenberg

(Photo by: David Allen)

* * * * * * * * * *

In 1981, Joe Sears and Jaston Williams introduced audiences in Austin, Texas to the citizens of Greater Tuna. The

Greater Tuna franchise grew over the years because of the small-town charm of its characters and the dexterity with which Sears and Williams handled quick costume changes as they jumped from one character to another. Unfortunately, the last time I saw them perform one of their plays the thrill was gone, the script was weak, and the performers seemed to be navigating on autopilot.

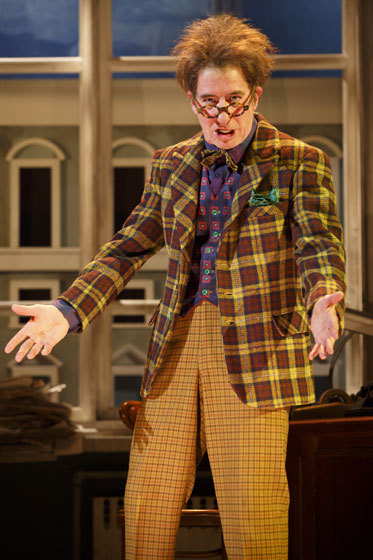

![2014-05-09-GreaterTuna1n.jpg]()

Jaston Williams and Joe Sears in Greater Tuna

In 1982, Michael Frayn's backstage farce about everything that could possibly go wrong in a stage production (

Noises Off) premiered in London and became a popular hit. Although the show has enjoyed numerous revivals, it failed to make a successful transition to the silver screen in 1992 when Peter Bogdonavich directed a cast that included Carol Burnett, Michael Caine, Christopher Reeve, John Ritter, and Marilu Henner. The verdict was that

Noises Off was too much of a live theatre experience to work as a film.

In September 1984, the Ridiculous Theatrical Company presented the world premiere of Charles Ludlam's deliciously zany spoof,

The Mystery of Irma Vep, with Ludlam and his partner (Everett Quinton) entertaining their audience with wacky costume/character changes and a surprise ending. According to Wikipedia, in 1991

Irma Vep was the most produced play in the United States.

![2014-05-09-Charleludlam.jpg]()

Everett Quinton and Charles Ludlam in

1984's The Mystery of Irma Vep

In June of 2005, Patrick Barlow's hilarious adaptation of a popular 1935 film premiered at the West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds. Its director, Fiona Buffini, had four actors recreating Alfred Hitchcock's screen adventure,

The 39 Steps, as they jumped through lighting-fast costume changes and a dizzying array of characters in a highly-stylized and monstrously inventive stage production.

Some comedic tricks hit their mark and never fail to please. Others lose their sting after their first time up at bat. The urge to cherry pick the best qualities of past comedic successes and merge them into a new (yet old-fashioned) mashup can be irresistible. But there are times when resistance is definitely called for.

It's understandable that a creative team might hope to merge the best elements of shows like

Noises Off and

The 39 Steps in order to capture the kind of comic gold and commercial success that each of those stage comedies achieved on its own. But lightning doesn't always strike in the same place, in the same way, and with the same force, as Steven Suskin admirably explains in his Huffington Post review of

Bullets Over Broadway (Aisle View: Don't Speak! Don't Sing!) while meticulously describing how a structural quirk in the new musical continually sabotages the show's comedic momentum.

![2014-05-09-hound1.jpg]()

Darren Bridgett and Michael Gene Sullivan in

The Hound of the Baskervilles (Photo by: Tracy Martin)

Created in 2007 by Steve Canny and John Nicholson for a small British theatrical company named Peepolykus, a comic adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle's 1901 Sherlock Holmes novel,

The Hound of the Baskervilles, became a sizable hit in Great Britain. It has since delighted audiences in numerous cities.

What happens when the intended comedic magic fails to materialize onstage? When a fierce farce feels forced, fertile fun flees a futile fantasy. Instead of the audience feeling like they're feasting on fresh fruit, its faith flutters in fear of failure as it feeds on a fallen souffle filled with flaccid shtick.

Get it? Got it? Good!

![2014-05-09-hound2.jpg]()

Darren Bridgett and Michael Gene Sullivan as two country yokels

in The Hound of the Baskervilles (Photo by: Tracy Martin)

That pretty much sums up the energetic (but lame) performance of

The Hound of the Baskervilles that I saw down at TheatreWorks (which fully deserved to be subtitled "This Turd Won't Hunt"). Darren Bridgett, Michael Gene Sullivan, and Ron Campbell (who spent several years as one of Cirque du Soleil's leading clowns) are all accomplished performers who were working hard onstage.

What could possibly have gone wrong? Several hunches pin the blame in surprising places:

- Because I was unable to attend the production's opening night (where members of the audience are frequently welcomed with a free glass of wine), I caught up with The Hound of the Baskervilles at a midweek performance which draws a more sedate audience less driven by the thrill of attending an "event."

- As a critic, I've already sat through several performances of The 39 Steps (including a January 2011 TheatreWorks production directed by Robert Kelley). It could very well be that the novelty of this particular production style has worn thin, causing me to feel as if The Hound of the Baskervilles was a similar product that was simply late to market.

- Whereas the characters in Game On and Wittenberg were motivated by their passions and/or obsessions, none of the characters in The Hound of the Baskervilles exhibited any sense of personal need. At numerous times during the evening, it seemed as if the performers were on a treadmill, trying to keep up with the demands of their rapid costume changes. I never felt any sense of dramatic urgency that could heighten the fun.

- Because of the way the comedy has been structured, the actors occasionally step out of character to address the audience -- even bitching about written complaints (fictional) that were submitted by members of the audience at intermission. At the beginning of Act II, one actor insists on starting all over again and performing a compressed, hyperactive version of Act I to prove to those who complained just how wrong they were. Sometimes a gimmick doesn't work. This one landed with a resounding thud.

- It's quite possible that, despite the current fascination with television and film treatments of Sherlock Holmes, the TheatreWorks audience was not especially familiar with Arthur Conan Doyle's story of The Hound of the Baskervilles. As a result, some of the jokes which might titillate Sherlock Holmes fans may have completely lost their punch.

![2014-05-09-hound3.jpg]()

Darren Bridgett and Ron Campbell in a scene from

The Hound of the Baskervilles (Photo by: Mark Kitaoka)

Ironically, the experience awakened long-buried memories of a dreary Broadway musical entitled

Baker Street, which opened on Broadway in February 1965 and whose exquisite sets (designed by Oliver Smith) were far more impressive than the show's book, score, or Hal Prince's stage direction. Although the cast was headed by such theatrical stalwarts as Fritz Weaver (Sherlock Holmes), Martin Gabel (Professor Moriarty), and Inga Swenson (playing a stage actress named Irene Adler),

Baker Street is rarely, if ever performed. Consigned to oblivion, it offers a tiny footnote to the history of the Great White Way as the show that marked the Broadway debuts (in small supporting roles) of Tommy Tune and Christopher Walken.

![2014-05-09-bakerstreet.jpg]()

Martin Gabel, Fritz Weaver, and Inga Swenson in 1965's Baker Street

To read more of George Heymont go to My Cultural Landscape