The paintings and drawings on view in April Gornik's current show at Danese/Corey -- roiling seas, active skies, and serenely lit forests -- come across as truthful. Gornik believes that "truth should involve complication" and the apparent beauty of her paintings is heightened by the artist's awareness of the circumstances and forces surrounding them.

Just as John Constable's paintings of the English countryside hinted that the Industrial Revolution was bringing change to the landscape, Gornik's world is permeated by her wistful recognition of environmental forces. She loves the scenery she paints and her work doesn't have the requisite ironic distance of true postmodernism: Gornik is too much in touch with the way she feels about the landscape, and in its spiritual potential, to let a cerebral approach dominate.

I recently interviewed April and asked her about her work, her methods and her personal concerns and interests.

John Seed Interviews April Gornik:

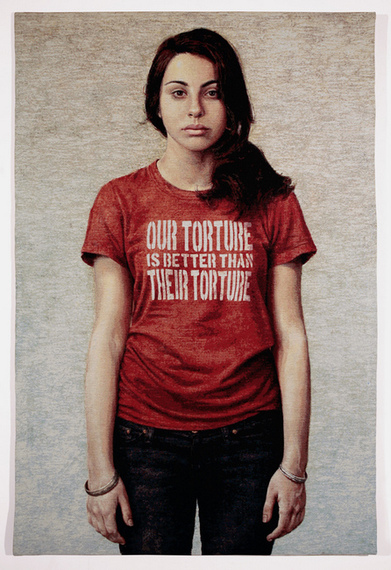

![2014-04-30-RalphGibsonphotoAprilGornik.jpg]()

April Gornik: Photo by Ralph Gibson

Tell me a bit about your early life and education. When did you know that you were an artist?

I was raised by my well-read but stay-at-home mom and my jazz trombone-playing tax accountant dad in a suburb on the east side of Cleveland. I have a younger brother who is seven years my junior. I went to parochial schools, first attended the Cleveland Institute of Art and then transferred to the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design for my BFA.

My first realization of my commitment to art was when a guidance counselor I had for my senior year of high school said she couldn't fit my art class in that year's curriculum and I insisted pretty aggressively that it was my most important class because I was going to be an artist, so she had to make room for it, which surprised me as much as it did her. I did take that art class.

![2014-04-30-LightAftertheStorm2013001.jpg]() Light After the Storm, 2012, oil on linen, 78 x 104 inches

For more than 30 years you have consistently created beautiful images of the landscape and defied a cultural tendency towards being ironic. How did you find the guts to do that?

Light After the Storm, 2012, oil on linen, 78 x 104 inches

For more than 30 years you have consistently created beautiful images of the landscape and defied a cultural tendency towards being ironic. How did you find the guts to do that?

I have to mention that I was lauded at first for making ironic paintings referencing the history of landscape painting, and I just kept my mouth shut. Eventually people's inherent need for meaning and being moved took over, I guess, and I've been generally accepted as an eccentric. I don't think it's guts, it's some kind of necessity in myself.

![2014-04-30-snowfall001.JPG]() Snowfall, 2014, oil on linen, 72 x 108 inches

Tell me about your working methods and places. Do you work outdoors, in the studio, or both?

Snowfall, 2014, oil on linen, 72 x 108 inches

Tell me about your working methods and places. Do you work outdoors, in the studio, or both?

I work only in the studio. I get completely overwhelmed when I try to work directly from nature. An image usually strikes me because it has an eerie familiarity, like something I already know or feel deeply. Then the trick is to get the scale right, so I typically order a canvas or cut paper after I've worked the image out compositionally for the scale I imagine will suit it.

Composition is where my work gets its power, and the work gets reordered all along the process of its making, from the initial sketch -- which is usually worked out in Photoshop -- to the drawing on the canvas or paper, to the actual painting or drawing, all of which have lives of their own and changes and adjustments -- sometimes radical -- that necessarily occur.

![2014-04-30-RadiantLight2013.jpg]() Radiant Light, 2013, oil on linen, 78 x 90 inches

I know from social media that you have some personal interests in environmental and social issues. Tell me about some of the causes that interest you.

Radiant Light, 2013, oil on linen, 78 x 90 inches

I know from social media that you have some personal interests in environmental and social issues. Tell me about some of the causes that interest you.

Oh man: I have a lot of causes. I'm very concerned about climate change and preserving wilderness. I was asked long ago if my work were meant to be "ecological," and I always said "no," since it comes from a more inner, psychological place and I don't feel political about it, but now frankly if it inspires people to in some way care about the world and what a mess we've made of it, I'm thrilled.

I'm a big animal rights person. I think factory farming is one of the greatest examples of mass sociopathology ever. The ocean is a mess. Need I go on? I'm proud to be a treehugger. And I am very involved in local organizations out in Sag Harbor where I've been living. It's easy to go nuts if you try to actually take on the global scope of all these problems.

![2014-04-30-StormRainLight2013.jpg]() Storm, Rain, Light, 2013, oil on linen, 68 x 72 inches

On your website you present some thoughts about "Visual Literacy" and lament the fact that we are "bombarded" with images. Can you say a few things about how you became interested in this predicament, and how you are pushing back against it?

Storm, Rain, Light, 2013, oil on linen, 68 x 72 inches

On your website you present some thoughts about "Visual Literacy" and lament the fact that we are "bombarded" with images. Can you say a few things about how you became interested in this predicament, and how you are pushing back against it?

I'm not against the fact that we're bombarded with images, it's just a fact. I prefer it to being starved for them, but I worry about people not being able to experience the physicality of art because of it, and that's really the way that art works. There's nothing like a painting, in its scale and physicality, to connect to another person through the hand, decisions, and imagination expressed there by the artist.

Paintings to me are machines that generate emotion, thought, and real experience through what's been embedded there by the artist. If a person is inured to that from image overkill, they'll just see a painting as an image and not go into the hand within the work. It's a loss I'm trying to push against.

I think people need to be taught how to look at art just like they need to learn to read literature. And the best way by far to ensure that is if a person has had art classes and understands the mind-hand connection that way.

Tell me a bit about one or two of the works on view at Danese...

Well let's look at two tree works.

One of the paintings is called

Green Shade, which is a reference to that great Andrew Marvell poem. It was an image I came up with by collaging, in Photoshop, various photos I had of the woods out back behind our house. I wanted to do a painting that had a kind of midsummer feeling, ripe and full but with a certain amount of stirring in the leaves & the light. I wanted dappled light, which turned out to be pretty daunting to paint, and I wanted an almost vertiginous sense of entry into the painting, so there's a kind of tipping of some of the trunks of the trees, the ground, etc.

![2014-04-30-GreenShade2012001.jpg]() Green Shade, 2012, oil on linen, 72 x 108 inches

Green Shade, 2012, oil on linen, 72 x 108 inches

I start with a sketch, then work it out compositionally, then get the canvas -- and in this case I'd done another painting that was fall-like for my last show and have the intention to eventually make four seasons with the canvases the same size: 6 x 9 feet. Then I draw out the painting from the sketch, marking particular points from the sketch which are proportionate to the canvas exactly -- like where the fattest tree meets the top -- but then drawing in most of it freehand, then underpainting with colors that will I hope give some dimensionality to the top surface colors. I need to actually have a dimensional plane on the surface to work from: you can see that pretty clearly in the other paintings as well; vestiges of the underpainting coming through in spots.

Then comes a

loooong time of just painting away, and watching the painting move in a direction I hadn't anticipated, which almost always happens, adjusting for that, adding and subtracting whole areas, etc. This is finally followed by the long dance to the end of the painting where at that point it looks like a painting should fundamentally, but isn't good enough. So that entails endless small adjustments and occasionally major changes. In the case of

Green Shade the streaky lights and shadows of the forest floor were endlessly reworked. The color of the trunks of the trees kept changing: and then there's a point at which the painting just kind of closed up and was finished, and I couldn't get back into it.

![2014-04-30-Charcoal001.JPG]() Light Falling Through Trees, 2014, charcoal on paper, 36.25 x 50 inches

Light Falling Through Trees, 2014, charcoal on paper, 36.25 x 50 inches

I approach the drawings the same way, with a sketch, and again make adjustments as I work.

Light Falling Through Trees made the most radical shift from the Photoshop sketch I started with, as I opened up that sketch enormously in the drawing, taking out trees, changing the weight of the shadows, etc. In the case of the drawings I can't underpaint of course, but I do start with a lighter, harder charcoal and then work up to a much blacker one to activate the light that's inherent in the paper.

![2014-04-30-WaterWorld2013.jpg]() Water World, 2013, oil on linen, 78 x 70 inches

What are the emotions you hope people will feel standing in front of your paintings?

Water World, 2013, oil on linen, 78 x 70 inches

What are the emotions you hope people will feel standing in front of your paintings?

I like to think of the paintings as having the potential to generate different emotions in different people. I hope I build them well enough to do that, so that someone might feel a soaring, happy feeling looking at, say,

Radiant Light and someone else might feel a kind of vertigo and uneasiness at the way it shifts in front of you. Landscape for me is a complicated attempt to locate myself in the world spiritually and emotionally and there's never one single feeling I have looking at something that feels true -- as opposed to real -- although many people just see that they're "realistic."

Truth should involve complication.

***

April Gornik Recent Paintings and Drawings

April 25 - May 31, 2014

Danese/Corey

511 West 22 Street

New York, NY 10011

Note: A new book,

April Gornik: Drawings is being released this month by FigureGround Press and distributed by D.A.P. The book includes essays by Steve Martin and Archie Rand, an interview conducted by Lawrence Weschler, and a composition for piano and cello by Bruce Wolosoff. A book signing will be held at Danese/Corey on May 29 from 5 to 7 p.m.

The catalog for

Recent Paintings and Drawings can be purchased on blurb.com (see below):