*Co-authored by Karina Eileraas

It's not that Martin Scorsese's most recent opus, The Wolf of Wall Street needs yet another review; it's the attempt by the film's star, perennial Scorsese muse Leonardo DiCaprio, to qualify it and Scorsese as "punk rock" that drew our ire and forced our pen.

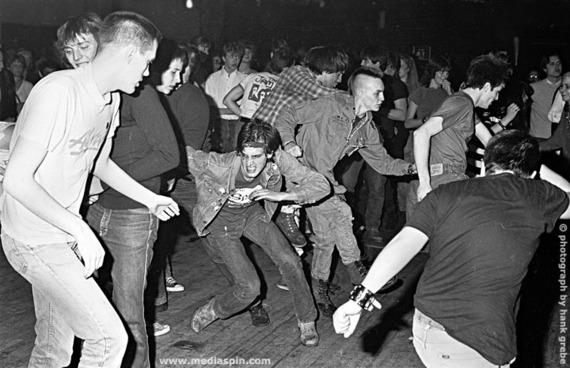

"Punk rock" (or "punk"), as we 40 and fifty-somethings grew up with it, originally designated the purposeful, near-tactically ugly outsider in culture and society. It connoted a rage against the machine, and the riposte of the caste-less, voiceless and marginalized to the self-appointed Brahmins of music, fashion, literature and other dominant calibrators of the wider Western consumerist-driven Zeitgeist. Punk attitude arguably began with rock n' roll in the 1950s, enjoyed a definitive political period in the mid-1970s as a volatile instrument of class warfare, continually reinvented itself throughout the 1980s as a suburban rite of passage against a Reagan-rechristened corporate America, and returned in the 1990s as grrl bands like Hole, Bikini Kill, Babes in Toyland and Lunachicks fused strategic performances of ugliness with a trenchant send-up of conventional codes of "pretty" femininity and domesticity.

Punk songs were written by refreshingly hideous-looking garage bands with broken instruments and, quite often, at least an initial inability to play music. Punk was egalitarian in spirit, featuring a do-it-yourself aesthetic as a means of exorcising one's externally conditioned demons.

By contrast, WOWS carried a $100 million budget, featured The Most Attractive Actor In Hollywood, had an aggressive marketing effort backing it, and was produced by former investment bankers and a vertically integrated studio that deferred sheepishly to Martin Scorsese as Hutts yielded to Jabba.

Punk songs of the 1970s were purposefully raw and concise as an answer to the hyper-produced seven-plus minute indulgences of such corpulent corporate bands as The Eagles, Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, Rush and Emerson, Lake & Palmer (E,L&P). The three-hour redundant profligacy of WOWS is more akin cinematically to excesses of the pre-punk period including "Tarkus" by E, L & P, "Inferno" by Metamorfosi and "Starship Trooper" by Yes.

Not only did punk value brevity, it outright rejected the sociopolitical and economic status quo. Openly critical of bourgeois morality and amorality, punk sought to upend dominant cultural values and unsettle the mainstream. Conversely, WOWS proffers a trite, masculinist narrative of rags-to-riches "success" in America. Despite the filmmakers' expression of intent to position the film as "warning," and their defense of its exhausting, relentless imagery as simply a mirror for the soullessness of the characters portrayed, WOWS aims to capture a wide audience precisely by articulating an ejaculatory fantasy of the male moneyed elite.

Plus, the filmmakers themselves are, to an extent, the victims of what they're supposedly warning us about. Scorsese lost all sense of nuance by reliving, via some sort of narrative regression therapy, his own lifestyle in the 1970s, as he attested to French press.1 DiCaprio retains a penchant for playing Jordan Belfort-type deviants, what with his prior work in Gangs of New York, Catch Me If You Can, The Departed, Django Unchained and Gatsby.2 Astonishingly, the actor even endorsed his character, the real WOWS, in a viral video sponsored by Belfort's speaking agent.

WOWS is "punk rock" to the extent that shopping at the mall chain store Hot Topic can be imagined as subversive. Indeed, if WOWS qualifies as a "punk rock film," then we have reached a cultural moment at which punk is devoid of meaning, reduced to crass commercial form in which the very possibility of rebellion signifies absolutely nothing. For WOWS does nothing to reject contemporary morality. Instead, merely by grandstanding, it endorses values of fear-driven greed, exploitation, hyper-consumption, hubris, misogyny and sociopathy. DiCaprio's characterization of the film as punk suggests that we have reached the very limits of our cultural ability to imagine the genuinely seditious in commercial art. To accept his assessment is to be reduced to what Michel Foucault described as "speaker's benefit", or false liberation, in which one believes that one is being subversive simply by speaking about subjects like sex that are endlessly narrated and perceived as "taboo."3

You want a true punk rock movie? Watch Steve McQueen's Shame, which tackles uncomfortable subjects -- online pornography and sex addiction -- in a manner that no one else would touch, let alone be able to produce. Shame made audiences necessarily distraught, but not because it lacked irony while presenting a punishing overabundance of debaucherous imagery. Shame isolates the viewer's subconscious compulsions on a vital issue people knee-jerkedly avoid while not running the risk of motivating its viewers towards its subject of deviance.

By contrast, WOWS ploughs away at a well-worn category that now rivals the banality of, well, gangster movies. The greed genre is done. Films like Wall Street I and II, Boiler Room, Margin Call, Glengarry Glen Ross, The Prime Gig, Rogue Trader, Arbitrage, The Company Men, The Social Network, et al. have already accomplished plenty over the past three decades in showing the dangers of runaway avarice alongside its enticements. If anything, said films tend to motivate latent sociopaths to pursue graft as a career. One of us worked in an actual financial "boiler room" in the financial services sector, where memorable lines from Boiler Room and Glengarry Glen Ross were quoted in the office to arouse the sales force. Lines such as "coffee's for closers," "ABC - always be closing," "attention-interest-decision-action," "motion creates emotion," "who's gonna close, you or him?!" and "anyone who says money is the root of all evil doesn't have any," were recited like Caddy Shack dialogue in a college dorm. It is painful to consider what additional scripts WOWS will add to that arsenal of corporate trench warfare lexicon, helping mold future robots to fleece the public.

True punk does battle with that which Walter Benjamin has described as the "emergency" of the status quo.4 As social movement, musical intervention and historical pause, punk stages deliberate flight from stultifying, corporatized visions of "taste," "value," and "success" as well as bourgeois incitements to conformity that permeated the collective unconscious especially in the 1970s U.S. and U.K. Punk interrupts tired, recycled narratives in favor of insurgent flights of imagination, launched with acerbic wit and tongue-in-cheek awareness that "if we keep speaking the same language, we're going to reproduce the same history."5

Punk is a challenge to the root emotion of fear. Fear of anything; abusive parents; creativity-squashing, Prussian-modeled compulsory schooling; misperceived poverty and inadequacy; conglomerated lifestyles that produce alcoholism and divided families; exhibiting compassion for fear of appearing weak; and corporate prescriptions for how to think about art. All of it.

Because WOWS fails to explore the ontological basis of all greed as being rooted in fear and self-loathing, it loses the plot and betrays its greatest potential service as art. Rather than equating "punk rock" filmmaking with the film's superficial shock value alone, DiCaprio and Scorsese might have dared to expose the raw edges of a collective cultural psyche that idolizes and exploits the most profound form of colonization imaginable: a subconscious frenzy of self-loathing molded by the mainstream media and wider advertising milieu.

WOWS thus misses a vital opportunity to engage with the core fear to which Belfort himself attests in his memoirs: the fear of not belonging. Of inadequacy versus the WASP-y lifestyles Belfort felt he'd never be allowed to access. Disappointingly, the film doesn't go there. Besides, DiCaprio is too WASP-looking to fit his character's off-screen reality. Leo was thus miscast, and the screenplay incomplete, despite Leo initiating the project and despite it being the longest film Scorsese has ever made (yet). As such, WOWS also manages to hint at the corporate culture in Hollywood of a systemic sycophancy so imbedded that no one -- from script coverage to post production -- dare question the claimed integrity of the creative endeavor at hand, lest they endanger their jobs. That too is far removed from the punk ethos.

In essence, the filmmakers' perspectives call into question the dominant interests of one of the most powerful "social networks" in contemporary culture: Hollywood itself. To the extent that Hollywood remains a boys' club, Scorsese's latest cinematic journey echoes not as "punk rock" but as symptomatic of the costs of belonging to a creative community in which certain voices, visions, and stories -- namely those that will not attract A-list talent or be perceived as sexy enough to generate box office receipts -- are excluded because they remain too "costly" to express.

Indeed, the to-date commercial success of WOWS reveals the inner workings of a corporate mythmaking machine that suppresses the very possibility of genuinely alternative storytelling. By repeating ad nauseum tales of men who cling tenaciously to psychologically bankrupt visions of success, Hollywood inspires reverence for those who have "made it," achieved belonging or gained entry in the most conventional sense conceivable. By inserting Jordan Belfort into the film's ending, in as hackneyed a cameo as one can imagine, the filmmakers genuflect toward said contingent. Most perniciously, they discourage truly punk experimentation by exerting an iron grip on the collective imagination.

It is precisely that fear of not fitting in that drives the inhumane pace of Wall Street itself, and to which punk can respond with the gnarling sound, vision and fury of the proud perpetual outsider. Quintessential outcasts, the truly "punk rock" innovate in the margins of society. Shunned as "unproductive" pariahs, many opt to linger on the fringes of the mainstream because they rightly perceive the price of said belonging as too high.

Footnotes

1 "J'avoue qu'il y a certains éléments, dans le personnage de Leonardo DiCaprio, qui sont autobiographiques. » ("I admit that there are certain elements in Leonardo DiCaprio's character that are autobiographical.")

2 Leo also wanted American Psycho in the late '90s as well, but had to be talked out of it by his manager as he was coming off of his recent success in Titanic. One of us worked at a prominent talent agency back then and distinctly recalls the phone conversations.

3 Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume I.

4 "The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the 'state of emergency' in which we live is not the exception but the rule." Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History.

5 Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which Is Not One.