Vincent Desiderio, whose work is on view at Marlborough Gallery through February 8th, is a painter and critic whose works balance a cerebral, theoretical sensibility with powerful emotional cues. In particular, Desiderio's recent paintings incorporate notions of reification, a theory that refers to making something real or concrete despite an absence of evidence. The rich, heavily worked surface of the artist's paintings -- and his interest in sculptural forms -- demonstrate an engagement with materiality and process that vivify his ideas.

I recently spoke to Desiderio and was able to ask him about the sources and meanings of a few recent works and also about some of his key theories.

John Seed Interviews Vincent Desiderio

![2014-01-27-desiderio.jpg]()

Vincent Desiderio teaching at the New York Academy of Art

One thing you talk about in relation to your work is reification. I'm starting to understand it - it's a process making something abstract concrete - but perhaps you can tell me more about it.

There is an ironic edge to the use of the word reification in terms of making paintings because for me a successful painting remains in constant motion; evoking a sense of the perpetual present tense of being. It remains open ended, thus facilitating the flow of artistic thought that is always and everywhere streaming through the history of painting.

However, painting's greatest strength lies in its stasis, its capacity to produce the coup d'oeil, the momentary freezing of this motion. Recently my work has taken on a density that underscores the materiality of the image, a move diametrically opposed to the screen image or the photograph. I see this as related to the radical materiality of Courbet and his Socialist concerns. My pictures now have a technical weight, and so, a palpable presence that I feel more comfortable with. I tend to dwell on the staging of the technical procedures so that visual information is emitted at varying degrees of intelligibility and speed.

From the start, I recognize that the real idea of the picture resides in the way materials are coaxed into meaning.

![2014-01-27-desiderio_trans.jpg]()

Vincent Desiderio, Transubstantiation, 2013

Oil and mixed media on canvas mounted on board, 68 x 111 inches

Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, New York

![2014-01-27-detail_trans001.jpg]()

Surface detail of Transubstantiation: Photo - Thomas Wharton

The subject of sculpture comes up in your recent work: it is a subject that seems to lend itself to reification.

Yes, certainly. As subjects they lend themselves well to the way in which I want to paint. But all of the subjects that I paint are inextricably bound to the evolution of material manipulations; their organization constitutes a narrative in its own right. One might call it the technical narrative. This may or may not be at odds with its dramatic narrative ( the recognizable elements in my work that seem to be engaged in one activity or another). The sculptures in my paintings are frozen forms but are imbued with motion by the way they are contextualized by the paint itself.

![2014-01-27-desiderio_hitchcock001.jpg]()

Vincent Desiderio, Hitchcock's Hands, 2012

Oil and mixed media on canvas, 64 x 66 inches

Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, New York

What can you tell me about the painting Hitchcock's Hands?

To tell you the truth, that image is the most appropriated of any of the images in the show. It's taken from one of the opening sequences of the old Alfred Hitchcock Presents television show.

I wish I could tell you I own this image completely, but by painting it the way I painted it I wanted to own it; changing its scale, context and scumbling the hands until they seemed sculptural. I don't often do that kind of thing -- appropriate images directly -- but I simply couldn't resist. The eye in a box looks so much like an old box camera. Enucleated, it becomes a mere artifact.

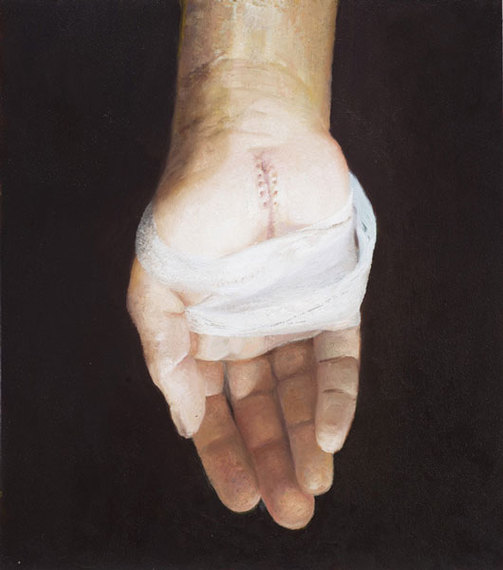

![2014-01-27-desiderio_hands.jpg]()

Vincent Desiderio, Study for Hand, 2012

Oil on board, 23 1/4 x 20 3/4 inches

Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, New York

Another image in your Marlborough show that intrigues me shows of a single hand with stitches and a dressing. How did that image come about?

That was a study for a picture that never materialized. I didn't spend much time on it before I realized it was going nowhere: a sutured stigmata.

In another interview you did, there was a mention of a quote that inspired you: Everything should be painted as if on a grey day...

It's from Delacroix. On May 5th, 1852, he made a curious journal entry describing color's relationships in terms of the optics of illumination, which anticipated the eventual subversion of form by color in avant-garde painting. Its substance is absolutely central to the artist's conception of color: both optically and as an allegorization of the exotic.

You see, for Delacroix half-light of a grey day represented an exotic realm where color was free to demonstrate its highly reflective propensity, undisturbed by incidents of direct light and shadow. In describing shadows as mirrors, Delacroix inferred that the reflective potential of objects untouched by direct light is obliterated by direct illumination. I think it is remarkable that Delacroix not only accords half-light privilege over classical light mass, but endows it with both optical truth and symbolic meaning. This was later fully played out in the divergent interests of the Impressionists and Post Impressionists.

One of your former students - Timoty Stotz - suggested I ask you this question: What is the difference between and symbol and an emblem?

A symbol is a representational tool, meaningful either through convention or association as a condensation of a more complex idea. An emblem -- as I have coined it -- is something that precipitates out of a soup of continuity, disrupting the viewer's suspension of disbelief.

When I have used the terms emblem or emblematic I am generally speaking of types of pictorial discourse. I distinguish between two types of technical narrativity: sequential and emblematic.

Sequential narrativity is a form of pictorial construction that privileges a continuity of effect linking the viewer, through the painting to the artist and his intention. It creates a seamless fictive whole characterized by a rapture or trance of viewing. The optical field opens before the spectator, inviting a kind of surrender to the picture's illusion (here used in a broad sense, inclusive of all sensually transmitted visual ideas). As such, he/she enters in to a kind of optical complicity with the work and through this complicity participates in a picture's narrativity. A visual experience of this nature suggests an orchestrated disclosure of intention -- on the part of the painter -- and an uncanny capacity to follow/participate in its unfolding (on the part of the viewer).

Conversely, the optical field can be made to shut down before the spectator, discouraging direct sensual participation. A visual event of this kind is interrupted by the presence of an element (emblem) removed from the sequence of normal comprehension or cultural utility and inserted within the visual field: like throwing a wrench in the works. This forces a more detached reading, emphasizing a critical model of experience over an undisturbed complicity. The expected meaning of an object and that meaning's continuity with experience are at odds with one another: essentially a re-contexutalization inviting redefinition. This de-familiarization signals a rupture in the stream of sequential disclosure. I call narratives of this type emblematic.

Can you give me an example of emblemization in a painting?

The development of emblemization is brilliantly demonstrated in Manet's three versions of The Execution of Maximillian, all date around 1867.

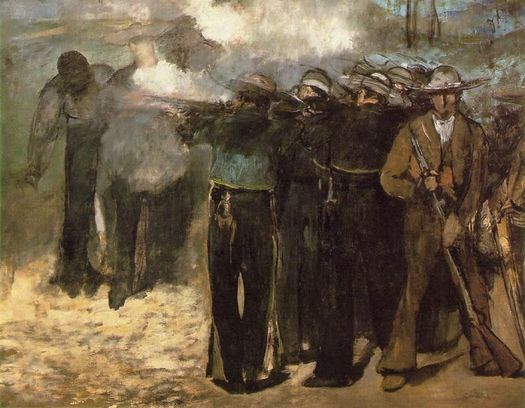

![2014-01-27-Manet_Boston.jpg]()

Édouard Manet, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867)

Oil on canvas, 195.9 x 259.7 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In the first (in Boston) a full-blown Romanticism is evident in the dense, smokey haze and swift and brutal brush strokes that speak directly to the violent death of the Emperor and his aides. Borne on a whirlwind of empathic disclosure, its reality contrasts sharply with the second version (in London) which is oddly dispassionate. Our spectatorial view removes us from the brutality of the action. The technical narratives of either picture offer no real surprises in terms of their sequential expectation: both are firmly rooted in pictorial practices that would have been instantly recognizable to their viewing publics.

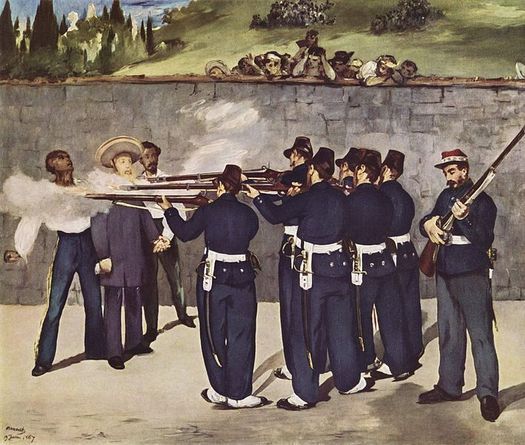

![2014-01-27-Manet_Mannheim.jpg]()

Édouard Manet, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868-69)

Oil on canvas, 252 x 305 cm., Kunsthalle Mannheim

The third version (in Mannheim) is a different story entirely. The detachment already discernible in the London version attains a level verging on visual agnosia. The figures are pure synthetic creations -- almost like decoupage -- lifted from one context and reinserted into another. One might interpret the abbreviated brushwork as lively reductions of form into the service of optical illusions, the way that works by Velasquez or Hals dissolve into vigorous masses of color at close range, while space is solidly established from a few meter's distance. The forms in the Mannheim Execution, however, un-resolvable at any distance, are marks isolated from their utility in the accomplishment of illusion. One is tempted to see them as signifiers detached from the onus of the signified: misquotations from the index of recognition.

Current Exhibition:

Vincent Desiderio

January 8th - February 8th

Marlborough Gallery, New York

40 W. 57th St.

Upcoming Exhibition:

THE BIG PICTURE

Desiderio, Fischl, Rauch, Saville, Tansey

January 28 - March 2, 2014

Opening Reception:

Tuesday, January 28, 6-8 PM

The New York Academy of Art

Wilkinson Gallery

Residency:

Vincent Desiderio will be resident Guest of Honor at the JSS in Civita Summer Art School & Residency 2014

I recently spoke to Desiderio and was able to ask him about the sources and meanings of a few recent works and also about some of his key theories.

John Seed Interviews Vincent Desiderio

One thing you talk about in relation to your work is reification. I'm starting to understand it - it's a process making something abstract concrete - but perhaps you can tell me more about it.

There is an ironic edge to the use of the word reification in terms of making paintings because for me a successful painting remains in constant motion; evoking a sense of the perpetual present tense of being. It remains open ended, thus facilitating the flow of artistic thought that is always and everywhere streaming through the history of painting.

However, painting's greatest strength lies in its stasis, its capacity to produce the coup d'oeil, the momentary freezing of this motion. Recently my work has taken on a density that underscores the materiality of the image, a move diametrically opposed to the screen image or the photograph. I see this as related to the radical materiality of Courbet and his Socialist concerns. My pictures now have a technical weight, and so, a palpable presence that I feel more comfortable with. I tend to dwell on the staging of the technical procedures so that visual information is emitted at varying degrees of intelligibility and speed.

From the start, I recognize that the real idea of the picture resides in the way materials are coaxed into meaning.

The subject of sculpture comes up in your recent work: it is a subject that seems to lend itself to reification.

Yes, certainly. As subjects they lend themselves well to the way in which I want to paint. But all of the subjects that I paint are inextricably bound to the evolution of material manipulations; their organization constitutes a narrative in its own right. One might call it the technical narrative. This may or may not be at odds with its dramatic narrative ( the recognizable elements in my work that seem to be engaged in one activity or another). The sculptures in my paintings are frozen forms but are imbued with motion by the way they are contextualized by the paint itself.

What can you tell me about the painting Hitchcock's Hands?

To tell you the truth, that image is the most appropriated of any of the images in the show. It's taken from one of the opening sequences of the old Alfred Hitchcock Presents television show.

I wish I could tell you I own this image completely, but by painting it the way I painted it I wanted to own it; changing its scale, context and scumbling the hands until they seemed sculptural. I don't often do that kind of thing -- appropriate images directly -- but I simply couldn't resist. The eye in a box looks so much like an old box camera. Enucleated, it becomes a mere artifact.

Another image in your Marlborough show that intrigues me shows of a single hand with stitches and a dressing. How did that image come about?

That was a study for a picture that never materialized. I didn't spend much time on it before I realized it was going nowhere: a sutured stigmata.

In another interview you did, there was a mention of a quote that inspired you: Everything should be painted as if on a grey day...

It's from Delacroix. On May 5th, 1852, he made a curious journal entry describing color's relationships in terms of the optics of illumination, which anticipated the eventual subversion of form by color in avant-garde painting. Its substance is absolutely central to the artist's conception of color: both optically and as an allegorization of the exotic.

You see, for Delacroix half-light of a grey day represented an exotic realm where color was free to demonstrate its highly reflective propensity, undisturbed by incidents of direct light and shadow. In describing shadows as mirrors, Delacroix inferred that the reflective potential of objects untouched by direct light is obliterated by direct illumination. I think it is remarkable that Delacroix not only accords half-light privilege over classical light mass, but endows it with both optical truth and symbolic meaning. This was later fully played out in the divergent interests of the Impressionists and Post Impressionists.

One of your former students - Timoty Stotz - suggested I ask you this question: What is the difference between and symbol and an emblem?

A symbol is a representational tool, meaningful either through convention or association as a condensation of a more complex idea. An emblem -- as I have coined it -- is something that precipitates out of a soup of continuity, disrupting the viewer's suspension of disbelief.

When I have used the terms emblem or emblematic I am generally speaking of types of pictorial discourse. I distinguish between two types of technical narrativity: sequential and emblematic.

Sequential narrativity is a form of pictorial construction that privileges a continuity of effect linking the viewer, through the painting to the artist and his intention. It creates a seamless fictive whole characterized by a rapture or trance of viewing. The optical field opens before the spectator, inviting a kind of surrender to the picture's illusion (here used in a broad sense, inclusive of all sensually transmitted visual ideas). As such, he/she enters in to a kind of optical complicity with the work and through this complicity participates in a picture's narrativity. A visual experience of this nature suggests an orchestrated disclosure of intention -- on the part of the painter -- and an uncanny capacity to follow/participate in its unfolding (on the part of the viewer).

Conversely, the optical field can be made to shut down before the spectator, discouraging direct sensual participation. A visual event of this kind is interrupted by the presence of an element (emblem) removed from the sequence of normal comprehension or cultural utility and inserted within the visual field: like throwing a wrench in the works. This forces a more detached reading, emphasizing a critical model of experience over an undisturbed complicity. The expected meaning of an object and that meaning's continuity with experience are at odds with one another: essentially a re-contexutalization inviting redefinition. This de-familiarization signals a rupture in the stream of sequential disclosure. I call narratives of this type emblematic.

Can you give me an example of emblemization in a painting?

The development of emblemization is brilliantly demonstrated in Manet's three versions of The Execution of Maximillian, all date around 1867.

In the first (in Boston) a full-blown Romanticism is evident in the dense, smokey haze and swift and brutal brush strokes that speak directly to the violent death of the Emperor and his aides. Borne on a whirlwind of empathic disclosure, its reality contrasts sharply with the second version (in London) which is oddly dispassionate. Our spectatorial view removes us from the brutality of the action. The technical narratives of either picture offer no real surprises in terms of their sequential expectation: both are firmly rooted in pictorial practices that would have been instantly recognizable to their viewing publics.

The third version (in Mannheim) is a different story entirely. The detachment already discernible in the London version attains a level verging on visual agnosia. The figures are pure synthetic creations -- almost like decoupage -- lifted from one context and reinserted into another. One might interpret the abbreviated brushwork as lively reductions of form into the service of optical illusions, the way that works by Velasquez or Hals dissolve into vigorous masses of color at close range, while space is solidly established from a few meter's distance. The forms in the Mannheim Execution, however, un-resolvable at any distance, are marks isolated from their utility in the accomplishment of illusion. One is tempted to see them as signifiers detached from the onus of the signified: misquotations from the index of recognition.

Current Exhibition:

Vincent Desiderio

January 8th - February 8th

Marlborough Gallery, New York

40 W. 57th St.

Upcoming Exhibition:

THE BIG PICTURE

Desiderio, Fischl, Rauch, Saville, Tansey

January 28 - March 2, 2014

Opening Reception:

Tuesday, January 28, 6-8 PM

The New York Academy of Art

Wilkinson Gallery

Residency:

Vincent Desiderio will be resident Guest of Honor at the JSS in Civita Summer Art School & Residency 2014