In Vie Privée et Publique des Animaux (The Private and Public Lives of Animals), first published in 1842, Animals of the world decide to do away with human oppression, and assemble a parliament on the site of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. All are delirious with joy, but, as they embrace, ". . . a duck was strangled by an overjoyed fox, a sheep by an enthusiastic wolf, and a horse by a delirious tiger." Many tales follow in which insects, reptiles and mammals make grandiloquent speeches, fight duels, and fall in love. But there is something the beasts are hiding, and only the pictures tell . . . . the animals are really humans in disguise!

J. J. Grandville, the illustrator, was not a politician or philosopher but a storyteller and even, arguably, the inventor of the graphic novel. In most of his books, the printed words do little more than summarize a story, and the pictures really tell it. They give new dimensions to what might otherwise be stereotypes. People are bestial while animals are human. Comic characters are sad, and tragic ones are funny. Nothing is ever what you expected.

Grandville generally preferred not mammals, which might have seemed a bit too "human" to him, or even birds but reptiles, amphibians, insects, arachnids, invertebrates, plants and machines as characters in his dramas. His animals dress in human clothing not to reveal their basic humanity but, rather, their (and our) essential strangeness.

Very few other artists have been able to fuse human and bestial features so completely, to a point where it is impossible to say which is prior. Animals, even plants and machines, in his work, share the human capacity for corruption, yet perhaps that is just another way of saying human beings share their innocence.

Here are a few of his illustrations, accompanied by brief notes and commentaries (Viewing this full screen is recommended, since the detail is often quite fine.):

![2014-03-13-211.jpg]()

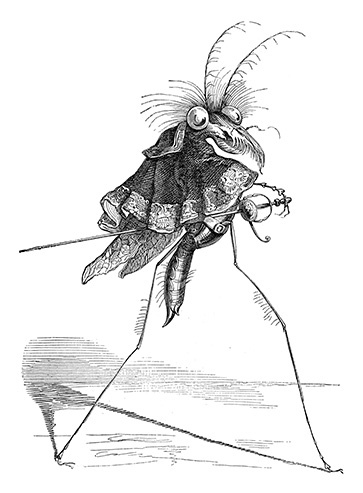

The misocamp, from Grandville's Vie Privée et Publique des Animaux

J. J. Grandville, the illustrator, was not a politician or philosopher but a storyteller and even, arguably, the inventor of the graphic novel. In most of his books, the printed words do little more than summarize a story, and the pictures really tell it. They give new dimensions to what might otherwise be stereotypes. People are bestial while animals are human. Comic characters are sad, and tragic ones are funny. Nothing is ever what you expected.

Grandville generally preferred not mammals, which might have seemed a bit too "human" to him, or even birds but reptiles, amphibians, insects, arachnids, invertebrates, plants and machines as characters in his dramas. His animals dress in human clothing not to reveal their basic humanity but, rather, their (and our) essential strangeness.

Very few other artists have been able to fuse human and bestial features so completely, to a point where it is impossible to say which is prior. Animals, even plants and machines, in his work, share the human capacity for corruption, yet perhaps that is just another way of saying human beings share their innocence.

Here are a few of his illustrations, accompanied by brief notes and commentaries (Viewing this full screen is recommended, since the detail is often quite fine.):

The misocamp, from Grandville's Vie Privée et Publique des Animaux