Wagner 201

On the Future of Wagnerism

![2014-02-06-RichardWagner95212021402.jpg]()

Do New Revelations of Hitler's Taste in Art Cast New Light on Wagner Appreciation?

![2014-02-06-AdolfHitler93401441402.jpg]()

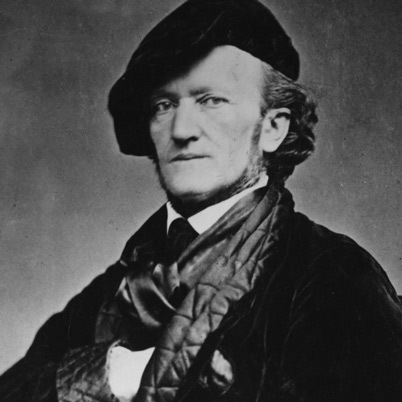

Widely regarded as one of history's greatest composers and artists, Richard Wagner is also widely known as one of history's most virulent anti-Semites. Like most opera lovers, I fell in love with Wagner. Yet my memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: Being Gay and Jewish in America, with an introduction by Gottfried Wagner, great-grandson of the composer, is the story of my own personal journey away from that love, and away from identifying myself as a Wagnerite.

As the AIDS epidemic began to unfold in 1981, I began to confront mortality as never before -- as a physican, as a writer, as a gay man, and as a Jew. At that time I had 5 pictures of Wagner on my living room wall, one of them a drawing by me. Not so coincidentally I began to come to grips with the extent of my own internalization of anti-Semitism, an odyssey of self-discovery that paralleled the great theme of my life up to that point, of coming out and into my own as a gay man. Slowly and painfully, I came to grips with the depth and seriousness of Wagner's anti-Semitism and its entanglements with what became Nazism. Past all the rationalizations commonly expounded by Wagnerites, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, I finally began to see that being a "Wagnerite," and especially a Jewish Wagnerite, was psychologically and morally troubled.

What's to be done about someone whose art is or seems to be so great, but whose prejudices were unquestionably contributory to great evil? How do you continue to appreciate art once aware of the enormity it was accessory to? This is the ring of fire that continues to surround composer Richard Wagner.

To judge from the way the still scorching controversies regarding Wagner and Wagner appreciation are playing out in our own time, there are several key strategies. First and foremost is to further extol the composer's art by finding ever new approaches and contexts of interpretation, the way we do with such other great artists as Sophocles and Shakespeare. Within this strategy of exhaustive reinterpretation is that of exploiting the passage of time and the receding of history. Still another, apposing strategy is to come clean about the seriousness and reach of the anti-Semitism, a process that has gained momentum in recent research and publications. Finally, there is the effort to humanize the composer by noting exceptions and contradictions in his biases, complexity in his rendering of villains and heroes alike, and examples of diversity in his circles, including a number of Jews and other non-Aryans. Between the lines of all these approaches is invariably a discernible longing if not impatience to get past...well, the past.

All of these strategies have been working together to further place the composer in perspective, a much larger process that, like all history, will continue to reconfigure over time. Today we can appreciate Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, even the Roman Coliseum or a southern plantation, without having that appreciation entirely vitiated by our knowledge of the atrocities of slavery and oppression that produced them and which they produced. Something comparable is happening with Wagner appreciation. It's anticipated that the controversies will eventually weaken and die, leaving just the art in their wake. The bathwater will finally get thrown out, the baby saved. This is the view that is almost universally shared by our arbiters of culture, whatever the intellectual acrobatics, re the present and future of Richard Wagner.

As we look to the future of Wagner and Wagnerism, the ill-defined cult of the composer that has no counterpart in all of music (there is no Beethovenism, Verdiism, Mozartism), we might consider the commentary of New Yorker music critic Alex Ross, an ardent Wagnerite who feels that pondering the Hitler connection with Wagner has gone too far. As he observed of his experience of the 2013 Wagner bicentennial Bayreuth Festival, "discussion of Wagner is stuck in a Nazi rut. His multifarious influence on artistic, intellectual, and political life has been largely forgotten; in the media, it is practically obligatory to identify him as 'Hitler's favorite composer.'" Ross looks forward to the time when can we get past the Wagner/Hitler detour and back onto the greater journey of Wagner appreciation.

Meanwhile, scholarship keeps casting new light on the composer. With the opening of previously inaccessible Bayreuth and other archives, there are ever-accumulating revelations of the already heavily documented relationships among Nazism, the Wagners and Bayreuth, and new insights on Hitler's reverence for Wagner. Alex Ross has been researching this material in preparation for a book, Wagner: Art in the Shadow of Music, that can be expected to try to distance the composer from Hitler. Why should one arch-criminal's appreciation of Wagner, which was--at least as Ross tries so hard to see it -- delimited and superficial, ruin everybody else's appreciation forever?

In July of 2013, Ross published an essay called "Othello's Daughter" in the New Yorker about a mixed race singer who studied with Wagner's widow, fiercely anti-Semitic Cosima Wagner, and who had been slated to be one of the Valkyries in Bayreuth's first fully staged Ring cycle. Ross understands the seriousness of Wagner's racism and anti-Semitism. In an earlier New Yorker piece, "Wagner in Israel," he wrote what seemed a sensitive and insightful analysis, reminding us, among other twists and turns in the Wagner-and-the-Jews saga, that Theodore Herzl, founding father of the state of Israel, loved Wagner. Yet even as Ross notes the naivete of not exculpating so great a prejudice as racism and Wagner's role in it on the basis of a few exceptions, he appears to be a lot more seduced by "Othello's Daughter" and other such exceptions than he realizes. Much the way I myself, alongside virtually every Jewish and for that matter non-Jewish Wagnerite of my knowledge and acquaintance, have seized on comparable tidbits to redeem Wagner from the curse of Hitler and Nazism.

One of which, luring me presently like the Blumenmadchen in Parsifal from my Wagnerism apostasy, is the degree to which the composer seemed to foretell of his own fate. In the face of what appears at least for now to be an eternal curse with no way out, Wagner himself can be evermore clearly seen in such Wandering Jew-ish figures as The Flying Dutchman, The Wanderer and Kundry.

"The endless Nazi fixation is unsettling," Ross writes. "Hitler has won a posthumous victory in seeing his idea of Wagner become the defining one." Ross is so impatient with all this that he neglects to mention the special exhibit mounted at Bayreuth in 2012 and during the 2013 bicentennial festival called "Silenced Voices" (covered by Zachary Woolfe in the New York Times), commemorating the Wagner-and Bayreuth-associated Jewish musicians and singers, most of whom were murdered as a result of Bayreuth's collaborations with Hitler. Apparently more in keeping with the idea of celebrating the composer's bicentennial, Ross explored Wagner's writings on America, where the composer once considered moving, and Wagner landmarks in New York City and environs.

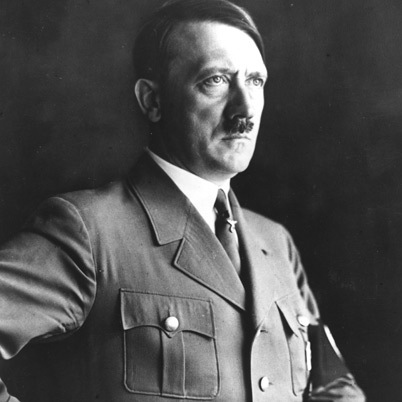

So henceforth we should be thinking of Wagner, like the Jews, as a victim of Hitler? What I came to see is that while there are some-of-his-close-associates-were-Jews puzzle pieces that don't fit neatly, the bigger picture is still strong and clear. Hitler really did understand Wagner and that understanding became the philosophical and spiritual basis of what became, under Hitler, Nazism. If Hitler happened to be an aesthetic peasant and vulgarian, his love of Wagner was certainly not regarded as such by most Wagner family members or many other notable Germans as being superficial, naive, delimited, even if that's what some really thought and a few brave artists and others gave voice to. On the contrary, as the Wagners -- especially Winifred (who married into the Wagner family) and with the notable exception of Friedelind (who fled Germany) -- and Bayreuth came to see it, Hitler was the culmination, the realization, of Wagner's Weltanshauung.

Meanwhile, new revelations about Hitler's art collections coincidentally invite a revisiting of Hitler's infatuation with Wagner. As it turns out, Hitler, whose favorite composer and sole acknowledged spiritual mentor was Wagner, was an even bigger fan of kitsch, of sentimentality and vulgarity in art, than anything we had already surmised. (See "Reading The Pictures: Fact is, We Can't Get Enough of Hitler," by Michael Shaw, HuffPost, Politics, 11/8/2013).

All of which suggests a different direction of inquiry than that being pursued by Ross and virtually all other Wagnerites. What if Hitler's appreciation of art and taste in art, including Wagner, is more clue than aberration? In other words, when all is said and done, as the long-silenced criticisms of Wagner's music dramas for being coarse, ponderous, pompous and bombastic begin to be reconsidered, is it possible that Wagner's art is really something closer to grandiloquent kitsch than classical Greek antiquity or Shakespeare? That Wagner might eventually be perceived as less rather than more of an artist seems to be an outcome that pretty much no one since Eduard Hanslick, the Jewish critic of Wagner so retaliatorily caricatured by Wagner in Die Meistersinger, has thought much about, much less dared to propose, certainly not in the current era of Wagner and Wagnerism.

As is clear from the example of Alex Ross, Wagner appreciation and with it Wagnerism will almost certainly continue its march forward. Eventually, Wagner's art will seem less and less tainted by anti-Semitism, its greatness unfettered by temporal and topical political considerations, distractions, detours, ruts. When appreciating Greek tragedy, how much do we now care about the wars and politics that cradled it? The same fate will almost certainly await Wagner, right? The only remaining question, certainly for Wagnerites, would seem to be how quickly can we get there.

Or is another outcome also possible? As time and Wagnerism solider onward, can it be that Wagner's art might seem less like that of the great Greek tragedians or Shakespeare and more like the pictures and statues of Schwarzwald moose that are emblematic centerpieces of Hitler's art collections and taste in art?

![2014-02-06-image272325galleryV9haps.jpg]()

And if so, can such a dethroning of Wagner be key to understanding Bayreuth's bicentennial Ring cycle production directed by iconoclast and "cultural terrorist" Frank Castorf, whose zeal in confounding preconceptions and expectations, in thwarting meaning and interpretation, seemed to have reached new heights of irreverence? "If the composer's great-granddaughters cannot guard Wagner's physical or artistic legacy, why are they in charge of the festival?" asked Neil Fisher in the London Times. Could no less than the heart and soul of Wagner appreciation, Bayreuth itself and the Wagner family, be setting the stage and direction for a more anarchic anti-future of Wagner appreciation?

And if so, finally, is such a "das Ende" not what Wagner himself foresaw and in the deepest sense accepted and even longed for?

______________

Lawrence D. Mass is the author of Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: Being Gay and Jewish in America.

biographical note: Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., is a cofounder of Gay Men's Health Crisis and was the first to write about AIDS in any press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another Or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He specializes in addiction medicine and lives in New York City

On the Future of Wagnerism

Do New Revelations of Hitler's Taste in Art Cast New Light on Wagner Appreciation?

Widely regarded as one of history's greatest composers and artists, Richard Wagner is also widely known as one of history's most virulent anti-Semites. Like most opera lovers, I fell in love with Wagner. Yet my memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: Being Gay and Jewish in America, with an introduction by Gottfried Wagner, great-grandson of the composer, is the story of my own personal journey away from that love, and away from identifying myself as a Wagnerite.

As the AIDS epidemic began to unfold in 1981, I began to confront mortality as never before -- as a physican, as a writer, as a gay man, and as a Jew. At that time I had 5 pictures of Wagner on my living room wall, one of them a drawing by me. Not so coincidentally I began to come to grips with the extent of my own internalization of anti-Semitism, an odyssey of self-discovery that paralleled the great theme of my life up to that point, of coming out and into my own as a gay man. Slowly and painfully, I came to grips with the depth and seriousness of Wagner's anti-Semitism and its entanglements with what became Nazism. Past all the rationalizations commonly expounded by Wagnerites, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, I finally began to see that being a "Wagnerite," and especially a Jewish Wagnerite, was psychologically and morally troubled.

What's to be done about someone whose art is or seems to be so great, but whose prejudices were unquestionably contributory to great evil? How do you continue to appreciate art once aware of the enormity it was accessory to? This is the ring of fire that continues to surround composer Richard Wagner.

To judge from the way the still scorching controversies regarding Wagner and Wagner appreciation are playing out in our own time, there are several key strategies. First and foremost is to further extol the composer's art by finding ever new approaches and contexts of interpretation, the way we do with such other great artists as Sophocles and Shakespeare. Within this strategy of exhaustive reinterpretation is that of exploiting the passage of time and the receding of history. Still another, apposing strategy is to come clean about the seriousness and reach of the anti-Semitism, a process that has gained momentum in recent research and publications. Finally, there is the effort to humanize the composer by noting exceptions and contradictions in his biases, complexity in his rendering of villains and heroes alike, and examples of diversity in his circles, including a number of Jews and other non-Aryans. Between the lines of all these approaches is invariably a discernible longing if not impatience to get past...well, the past.

All of these strategies have been working together to further place the composer in perspective, a much larger process that, like all history, will continue to reconfigure over time. Today we can appreciate Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, even the Roman Coliseum or a southern plantation, without having that appreciation entirely vitiated by our knowledge of the atrocities of slavery and oppression that produced them and which they produced. Something comparable is happening with Wagner appreciation. It's anticipated that the controversies will eventually weaken and die, leaving just the art in their wake. The bathwater will finally get thrown out, the baby saved. This is the view that is almost universally shared by our arbiters of culture, whatever the intellectual acrobatics, re the present and future of Richard Wagner.

As we look to the future of Wagner and Wagnerism, the ill-defined cult of the composer that has no counterpart in all of music (there is no Beethovenism, Verdiism, Mozartism), we might consider the commentary of New Yorker music critic Alex Ross, an ardent Wagnerite who feels that pondering the Hitler connection with Wagner has gone too far. As he observed of his experience of the 2013 Wagner bicentennial Bayreuth Festival, "discussion of Wagner is stuck in a Nazi rut. His multifarious influence on artistic, intellectual, and political life has been largely forgotten; in the media, it is practically obligatory to identify him as 'Hitler's favorite composer.'" Ross looks forward to the time when can we get past the Wagner/Hitler detour and back onto the greater journey of Wagner appreciation.

Meanwhile, scholarship keeps casting new light on the composer. With the opening of previously inaccessible Bayreuth and other archives, there are ever-accumulating revelations of the already heavily documented relationships among Nazism, the Wagners and Bayreuth, and new insights on Hitler's reverence for Wagner. Alex Ross has been researching this material in preparation for a book, Wagner: Art in the Shadow of Music, that can be expected to try to distance the composer from Hitler. Why should one arch-criminal's appreciation of Wagner, which was--at least as Ross tries so hard to see it -- delimited and superficial, ruin everybody else's appreciation forever?

In July of 2013, Ross published an essay called "Othello's Daughter" in the New Yorker about a mixed race singer who studied with Wagner's widow, fiercely anti-Semitic Cosima Wagner, and who had been slated to be one of the Valkyries in Bayreuth's first fully staged Ring cycle. Ross understands the seriousness of Wagner's racism and anti-Semitism. In an earlier New Yorker piece, "Wagner in Israel," he wrote what seemed a sensitive and insightful analysis, reminding us, among other twists and turns in the Wagner-and-the-Jews saga, that Theodore Herzl, founding father of the state of Israel, loved Wagner. Yet even as Ross notes the naivete of not exculpating so great a prejudice as racism and Wagner's role in it on the basis of a few exceptions, he appears to be a lot more seduced by "Othello's Daughter" and other such exceptions than he realizes. Much the way I myself, alongside virtually every Jewish and for that matter non-Jewish Wagnerite of my knowledge and acquaintance, have seized on comparable tidbits to redeem Wagner from the curse of Hitler and Nazism.

One of which, luring me presently like the Blumenmadchen in Parsifal from my Wagnerism apostasy, is the degree to which the composer seemed to foretell of his own fate. In the face of what appears at least for now to be an eternal curse with no way out, Wagner himself can be evermore clearly seen in such Wandering Jew-ish figures as The Flying Dutchman, The Wanderer and Kundry.

"The endless Nazi fixation is unsettling," Ross writes. "Hitler has won a posthumous victory in seeing his idea of Wagner become the defining one." Ross is so impatient with all this that he neglects to mention the special exhibit mounted at Bayreuth in 2012 and during the 2013 bicentennial festival called "Silenced Voices" (covered by Zachary Woolfe in the New York Times), commemorating the Wagner-and Bayreuth-associated Jewish musicians and singers, most of whom were murdered as a result of Bayreuth's collaborations with Hitler. Apparently more in keeping with the idea of celebrating the composer's bicentennial, Ross explored Wagner's writings on America, where the composer once considered moving, and Wagner landmarks in New York City and environs.

So henceforth we should be thinking of Wagner, like the Jews, as a victim of Hitler? What I came to see is that while there are some-of-his-close-associates-were-Jews puzzle pieces that don't fit neatly, the bigger picture is still strong and clear. Hitler really did understand Wagner and that understanding became the philosophical and spiritual basis of what became, under Hitler, Nazism. If Hitler happened to be an aesthetic peasant and vulgarian, his love of Wagner was certainly not regarded as such by most Wagner family members or many other notable Germans as being superficial, naive, delimited, even if that's what some really thought and a few brave artists and others gave voice to. On the contrary, as the Wagners -- especially Winifred (who married into the Wagner family) and with the notable exception of Friedelind (who fled Germany) -- and Bayreuth came to see it, Hitler was the culmination, the realization, of Wagner's Weltanshauung.

Meanwhile, new revelations about Hitler's art collections coincidentally invite a revisiting of Hitler's infatuation with Wagner. As it turns out, Hitler, whose favorite composer and sole acknowledged spiritual mentor was Wagner, was an even bigger fan of kitsch, of sentimentality and vulgarity in art, than anything we had already surmised. (See "Reading The Pictures: Fact is, We Can't Get Enough of Hitler," by Michael Shaw, HuffPost, Politics, 11/8/2013).

All of which suggests a different direction of inquiry than that being pursued by Ross and virtually all other Wagnerites. What if Hitler's appreciation of art and taste in art, including Wagner, is more clue than aberration? In other words, when all is said and done, as the long-silenced criticisms of Wagner's music dramas for being coarse, ponderous, pompous and bombastic begin to be reconsidered, is it possible that Wagner's art is really something closer to grandiloquent kitsch than classical Greek antiquity or Shakespeare? That Wagner might eventually be perceived as less rather than more of an artist seems to be an outcome that pretty much no one since Eduard Hanslick, the Jewish critic of Wagner so retaliatorily caricatured by Wagner in Die Meistersinger, has thought much about, much less dared to propose, certainly not in the current era of Wagner and Wagnerism.

As is clear from the example of Alex Ross, Wagner appreciation and with it Wagnerism will almost certainly continue its march forward. Eventually, Wagner's art will seem less and less tainted by anti-Semitism, its greatness unfettered by temporal and topical political considerations, distractions, detours, ruts. When appreciating Greek tragedy, how much do we now care about the wars and politics that cradled it? The same fate will almost certainly await Wagner, right? The only remaining question, certainly for Wagnerites, would seem to be how quickly can we get there.

Or is another outcome also possible? As time and Wagnerism solider onward, can it be that Wagner's art might seem less like that of the great Greek tragedians or Shakespeare and more like the pictures and statues of Schwarzwald moose that are emblematic centerpieces of Hitler's art collections and taste in art?

And if so, can such a dethroning of Wagner be key to understanding Bayreuth's bicentennial Ring cycle production directed by iconoclast and "cultural terrorist" Frank Castorf, whose zeal in confounding preconceptions and expectations, in thwarting meaning and interpretation, seemed to have reached new heights of irreverence? "If the composer's great-granddaughters cannot guard Wagner's physical or artistic legacy, why are they in charge of the festival?" asked Neil Fisher in the London Times. Could no less than the heart and soul of Wagner appreciation, Bayreuth itself and the Wagner family, be setting the stage and direction for a more anarchic anti-future of Wagner appreciation?

And if so, finally, is such a "das Ende" not what Wagner himself foresaw and in the deepest sense accepted and even longed for?

______________

Lawrence D. Mass is the author of Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: Being Gay and Jewish in America.

biographical note: Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., is a cofounder of Gay Men's Health Crisis and was the first to write about AIDS in any press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another Or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He specializes in addiction medicine and lives in New York City