THE LONELINESS OF THE LONG DISTANCE RUNNER ** out of ****

MACHINAL *** out of ****

THE LONELINESS OF THE LONG DISTANCE RUNNER ** out of ****

ATLANTIC THEATER COMPANY

This play is just 80 minutes in length but it's a long 80 minutes because we learn everything we're ever going to know about our hero in the first five minutes. The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner is based on the classic Angry Young Man British film that launched the career of actor Tom Courtenay. He's a teen sentenced to a boys reformatory (essentially, prison) for a petty robbery. But his skill as a runner earns him privileges and the movie shows this young man Colin running while reflecting on his life and what brought him to this moment -- wondering if winning the race will just make him a pawn to the Man, the System.

The play follows the same trajectory, but it's been updated to take place just after recent riots in London and our hero is now black. He's also noticeably less angry. In the film, Courtenay is literally bristling with unfocused anger at everything and everyone. Life, the government, his dying father, the mother who was cheating on his dying father and whom -- wrongly -- Colin believes killed him by withholding pain medication. Colin is furious over her new boyfriend and the spectacle of his mother wasting insurance money on a flurry of clothes and the like. In other words, Colin is very, very angry and in many ways has every confused reason to be so.

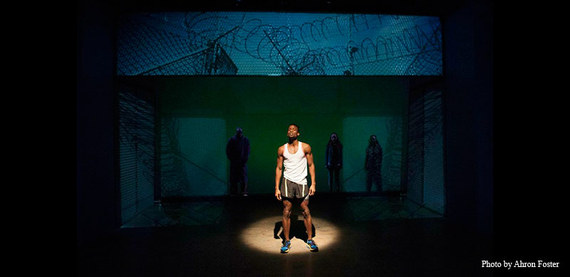

But this stage adaptation by Roy Williams confuses things. Perhaps because Colin is now black they were afraid to show him as furiously angry with the world, fearing cliche or that Colin might be dismissed as a thug. The very appealing Sheldon Best plays Colin and wins us over immediately with his rather reasonable, sensible approach to an aimless life.

![2014-01-22-ldr_web_08.jpg]()

(photo by Ahron Foster)

He didn't take part in the rioting and looting and seems to have a good head on his shoulder, at least for a kid with very few prospects. His mom didn't cheat on his dying dad or add to the man's pain. All of this makes Colin appealing but far less volatile. When he actually instigates a petty theft of a bakery, it makes no sense based on what we know of him.

Indeed, the play removes almost everything about Colin that made sense, especially his injured fury. The movie was part of the British New Wave, which is literally known as the Angry Young Man movement. Colin has plenty of reasons to be angry at a bankrupt economy and dim prospects for work (which, to be fair, doesn't really appeal to him). But the very real and personal reasons for his anger have been tamped down or removed and all we have is a young man we get to know who does a foolish act we don't understand.

The entire piece should lead up to his rebellion, the possibility that Colin will finally stand up to the System and refuse to play their game. He'll literally throw away the possibility of winning. In the 1950s, this had a certain symbolic appeal. In the context of today, however, it comes across as a sadly self-destructive act, not the first step to claiming piece of mind the way it was in the film. Truly, anyone who has never seen the movie will simply be puzzled by the action taking place.

![2014-01-22-ldr_web_19.jpg]()

(photo by Ahron Foster)

Though the script is lacking and various theatrical touches (like having cast members appear at times to the side or the back of the stage like a Greek chorus) simply fall flat, the show succeeds very well at its central conceit: showing Colin running a long distance race. Best is as mentioned a very likable presence, all the more remarkable since he delivers his dialogue often while running in place. The projection design by Pauline Lu & Paul Piekarz are top notch at evoking movement and various settings like some woods near the detention center Colin is held at. The tech elements overall are solid throughout. But kudos especially to Best's acting chops and fitness.

He has very good chemistry with Jasmine Cephas Jones as the potential romantic interest Kenisha. Indeed, the entire cast is solid, with Zainab Jah turning the contradictory role of Colin's Mum into a sensible, believable character and Raviv Ullman a handsome presence in dual roles as a scowling guard and later a friendly competitor in the race named Gunthorpe. Unfortunately, the key role of the would-be mentor Stevens is handled poorly by Todd Weeks. He never hints at the possible complexity of the character. Is Stevens using Colin for his own career, genuinely trying to help the lad or some complicated mix of the two? Instead, all we see is someone awkwardly emphasizing his dialogue and never letting us forget for a moment that he's an actor playing a role.

Director Leah C. Gardiner handles the many technical demands and the strong cast with assurance. It's a pity they didn't realize that updating and weakening the impetus for our hero's distress was cutting the legs out from under him.

Here's the trailer to the original British film.

MACHINAL *** out of ****

ROUNDABOUT THEATRE COMPANY

Machinal means of or pertaining to machines. And life can certainly seem a grinding machine to one whose spirit is snuffed out -- one imagines -- even before it can begin. Coincidentally, "the Machine" was the nickname for the mammoth set design that dominated the recent production of Wagner's The Ring at the Metropolitan Opera. It was huge, it was noisy, and it sometimes seemed a lot of bother for just a few brief moments of epic beauty.

The Roundabout has revived writer Sophie Treadwell's 1928 play Machinal and it too has a flashy set design, a rotating box that is flashy and sometimes noisy and dominates the proceedings. But the Met might just sneak down to the Roundabout to see how perfectly this particular set design complements the play it was created for, how every turning of the set demonstrates how our heroine seems trapped on a treadmill leading right towards her fate: the electric chair. Sometimes it creaks and sometimes it groans but this is just right for a life that too rarely gives voice to its despair until a brutal and sad act of violence.

I've never seen Machinal before. It was apparently brought back to life by a revival at the Public in 1990, just before I arrived in New York and has become more of a fixture in the repertory ever since. My first impression is that the Roundabout has squeezed out about everything it can from a story that is sometimes avant-garde and often bloodless as it shows a woman who can barely breathe, much less control her own destiny. (The real-life murder that inspired it was much more Double Indemnity than the dehumanizing Metropolis on display here.)

Luckily, this high-minded work that might feel a bit dated has the wonderful, intelligent Rebecca Hall as the lead, a young woman who is so worn down by life she is referred to in the Playbill as simply Young Woman, which is to say Every Woman. She is late to work because the subway feels stifling and the Young Woman has a panic attack. Her dull as dishwater boss (Michael Cumpsty, excellent as always) asks her to marry him and this too sends her into a nervous tailspin. Her Mother (an effective Suzanne Bertish) is indifferent to her plight and confused when the Young Woman wonders if perhaps maybe she should actually love her potential husband, rather than shrink from his touch?

But the Machine is indifferent and life trudges on and she is married and on her honeymoon and crying and listening to her husband insist the blinds be drawn so no one can see in (and she can't see out) and a child is born but she can't bring herself to nurse it and the machine rotates and her life trudges on until out of nowhere she has a Lover (Morgan Spector, very good in a role first tackled by Clark Gable). For a moment, the Machine seems to pause and she is smiling and emotion is pouring through in a show that has heretofore seemed a bit dry, a bit didactic. It helps that Hall is in a slip and smiling and the strap of her clothing falls off her shoulder. Is happiness possible? We'll never know.

As mentioned, the play is based on a famous murder trial of the time but the inevitability it held in 1928 seems a bit hard to swallow. Why did her Lover go away? Was he uninterested in a long-term affair? (That's certainly hinted at.) But why didn't the Young Woman just divorce her husband? Are her frantic inner monologues simply a stream of consciousness that reflects her inner turmoil a la Virginia Woolf? Or is the Young Woman perhaps mentally ill, struggling as she does to handle day to day life?

This Machinal does not provide the satisfying answers or even emotional complexity that might make a lack of answers feel more like real life than just a play that simply has a predetermined finish line. But director Lyndsey Turner makes one happy to go along for the ride. The set design by Es Devlin is a tour de force but needless to say it wouldn't work without all the other technical elements being right in sync, from the costumes and lighting to the excellent sound design of Matt Tierney and the choreography of Sam Pinkleton.

Hall breathes life into what on paper seems more like a conceit and Cumpsty manages a wonderful balancing act. His role as the stultifying Husband might be played for buffoonish laughs or turned into a controlling monster. Cumpsty manages to get the laughs and some chilling moments ("Wait! WAIT!" he barks in one key scene) but he creates interesting tension and humor while letting the husband be exactly and essentially no more than what he is: dull. That is no easy task. Ashley Bell is vivid as a good-time Telephone Girl. And Ryan Dinning offers up every possible spin on "Hot dog!" known to man while using his body language to tell the story of a young man become rather willingly seduced in a bar.

Indeed, it's a faultless cast doing its best with a work far more unconventional than is usual for the Roundabout. Here's hoping their subscribers appreciate this nervy stretching of the definition of what a Roundabout production can be.

THEATER OF 2014

Beautiful: The Carole King Musical ***

Rodney King ***

Hard Times ** 1/2

Rosencrantz And Guildenstern Are Dead **

I Could Say More *

The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner **

Machinal ***

MACHINAL *** out of ****

THE LONELINESS OF THE LONG DISTANCE RUNNER ** out of ****

ATLANTIC THEATER COMPANY

This play is just 80 minutes in length but it's a long 80 minutes because we learn everything we're ever going to know about our hero in the first five minutes. The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner is based on the classic Angry Young Man British film that launched the career of actor Tom Courtenay. He's a teen sentenced to a boys reformatory (essentially, prison) for a petty robbery. But his skill as a runner earns him privileges and the movie shows this young man Colin running while reflecting on his life and what brought him to this moment -- wondering if winning the race will just make him a pawn to the Man, the System.

The play follows the same trajectory, but it's been updated to take place just after recent riots in London and our hero is now black. He's also noticeably less angry. In the film, Courtenay is literally bristling with unfocused anger at everything and everyone. Life, the government, his dying father, the mother who was cheating on his dying father and whom -- wrongly -- Colin believes killed him by withholding pain medication. Colin is furious over her new boyfriend and the spectacle of his mother wasting insurance money on a flurry of clothes and the like. In other words, Colin is very, very angry and in many ways has every confused reason to be so.

But this stage adaptation by Roy Williams confuses things. Perhaps because Colin is now black they were afraid to show him as furiously angry with the world, fearing cliche or that Colin might be dismissed as a thug. The very appealing Sheldon Best plays Colin and wins us over immediately with his rather reasonable, sensible approach to an aimless life.

He didn't take part in the rioting and looting and seems to have a good head on his shoulder, at least for a kid with very few prospects. His mom didn't cheat on his dying dad or add to the man's pain. All of this makes Colin appealing but far less volatile. When he actually instigates a petty theft of a bakery, it makes no sense based on what we know of him.

Indeed, the play removes almost everything about Colin that made sense, especially his injured fury. The movie was part of the British New Wave, which is literally known as the Angry Young Man movement. Colin has plenty of reasons to be angry at a bankrupt economy and dim prospects for work (which, to be fair, doesn't really appeal to him). But the very real and personal reasons for his anger have been tamped down or removed and all we have is a young man we get to know who does a foolish act we don't understand.

The entire piece should lead up to his rebellion, the possibility that Colin will finally stand up to the System and refuse to play their game. He'll literally throw away the possibility of winning. In the 1950s, this had a certain symbolic appeal. In the context of today, however, it comes across as a sadly self-destructive act, not the first step to claiming piece of mind the way it was in the film. Truly, anyone who has never seen the movie will simply be puzzled by the action taking place.

Though the script is lacking and various theatrical touches (like having cast members appear at times to the side or the back of the stage like a Greek chorus) simply fall flat, the show succeeds very well at its central conceit: showing Colin running a long distance race. Best is as mentioned a very likable presence, all the more remarkable since he delivers his dialogue often while running in place. The projection design by Pauline Lu & Paul Piekarz are top notch at evoking movement and various settings like some woods near the detention center Colin is held at. The tech elements overall are solid throughout. But kudos especially to Best's acting chops and fitness.

He has very good chemistry with Jasmine Cephas Jones as the potential romantic interest Kenisha. Indeed, the entire cast is solid, with Zainab Jah turning the contradictory role of Colin's Mum into a sensible, believable character and Raviv Ullman a handsome presence in dual roles as a scowling guard and later a friendly competitor in the race named Gunthorpe. Unfortunately, the key role of the would-be mentor Stevens is handled poorly by Todd Weeks. He never hints at the possible complexity of the character. Is Stevens using Colin for his own career, genuinely trying to help the lad or some complicated mix of the two? Instead, all we see is someone awkwardly emphasizing his dialogue and never letting us forget for a moment that he's an actor playing a role.

Director Leah C. Gardiner handles the many technical demands and the strong cast with assurance. It's a pity they didn't realize that updating and weakening the impetus for our hero's distress was cutting the legs out from under him.

Here's the trailer to the original British film.

MACHINAL *** out of ****

ROUNDABOUT THEATRE COMPANY

Machinal means of or pertaining to machines. And life can certainly seem a grinding machine to one whose spirit is snuffed out -- one imagines -- even before it can begin. Coincidentally, "the Machine" was the nickname for the mammoth set design that dominated the recent production of Wagner's The Ring at the Metropolitan Opera. It was huge, it was noisy, and it sometimes seemed a lot of bother for just a few brief moments of epic beauty.

The Roundabout has revived writer Sophie Treadwell's 1928 play Machinal and it too has a flashy set design, a rotating box that is flashy and sometimes noisy and dominates the proceedings. But the Met might just sneak down to the Roundabout to see how perfectly this particular set design complements the play it was created for, how every turning of the set demonstrates how our heroine seems trapped on a treadmill leading right towards her fate: the electric chair. Sometimes it creaks and sometimes it groans but this is just right for a life that too rarely gives voice to its despair until a brutal and sad act of violence.

I've never seen Machinal before. It was apparently brought back to life by a revival at the Public in 1990, just before I arrived in New York and has become more of a fixture in the repertory ever since. My first impression is that the Roundabout has squeezed out about everything it can from a story that is sometimes avant-garde and often bloodless as it shows a woman who can barely breathe, much less control her own destiny. (The real-life murder that inspired it was much more Double Indemnity than the dehumanizing Metropolis on display here.)

Luckily, this high-minded work that might feel a bit dated has the wonderful, intelligent Rebecca Hall as the lead, a young woman who is so worn down by life she is referred to in the Playbill as simply Young Woman, which is to say Every Woman. She is late to work because the subway feels stifling and the Young Woman has a panic attack. Her dull as dishwater boss (Michael Cumpsty, excellent as always) asks her to marry him and this too sends her into a nervous tailspin. Her Mother (an effective Suzanne Bertish) is indifferent to her plight and confused when the Young Woman wonders if perhaps maybe she should actually love her potential husband, rather than shrink from his touch?

But the Machine is indifferent and life trudges on and she is married and on her honeymoon and crying and listening to her husband insist the blinds be drawn so no one can see in (and she can't see out) and a child is born but she can't bring herself to nurse it and the machine rotates and her life trudges on until out of nowhere she has a Lover (Morgan Spector, very good in a role first tackled by Clark Gable). For a moment, the Machine seems to pause and she is smiling and emotion is pouring through in a show that has heretofore seemed a bit dry, a bit didactic. It helps that Hall is in a slip and smiling and the strap of her clothing falls off her shoulder. Is happiness possible? We'll never know.

As mentioned, the play is based on a famous murder trial of the time but the inevitability it held in 1928 seems a bit hard to swallow. Why did her Lover go away? Was he uninterested in a long-term affair? (That's certainly hinted at.) But why didn't the Young Woman just divorce her husband? Are her frantic inner monologues simply a stream of consciousness that reflects her inner turmoil a la Virginia Woolf? Or is the Young Woman perhaps mentally ill, struggling as she does to handle day to day life?

This Machinal does not provide the satisfying answers or even emotional complexity that might make a lack of answers feel more like real life than just a play that simply has a predetermined finish line. But director Lyndsey Turner makes one happy to go along for the ride. The set design by Es Devlin is a tour de force but needless to say it wouldn't work without all the other technical elements being right in sync, from the costumes and lighting to the excellent sound design of Matt Tierney and the choreography of Sam Pinkleton.

Hall breathes life into what on paper seems more like a conceit and Cumpsty manages a wonderful balancing act. His role as the stultifying Husband might be played for buffoonish laughs or turned into a controlling monster. Cumpsty manages to get the laughs and some chilling moments ("Wait! WAIT!" he barks in one key scene) but he creates interesting tension and humor while letting the husband be exactly and essentially no more than what he is: dull. That is no easy task. Ashley Bell is vivid as a good-time Telephone Girl. And Ryan Dinning offers up every possible spin on "Hot dog!" known to man while using his body language to tell the story of a young man become rather willingly seduced in a bar.

Indeed, it's a faultless cast doing its best with a work far more unconventional than is usual for the Roundabout. Here's hoping their subscribers appreciate this nervy stretching of the definition of what a Roundabout production can be.

THEATER OF 2014

Beautiful: The Carole King Musical ***

Rodney King ***

Hard Times ** 1/2

Rosencrantz And Guildenstern Are Dead **

I Could Say More *

The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner **

Machinal ***