Co-authored by Catherine Tedford who directs the Richard F. Brush Art Gallery at St. Lawrence University and writes about street art stickers on her research blog Stickerkitty. On behalf of the NY6 Think Tank.

You might not have observed what is called "street art stickers" before, but once you do, you'll start seeing them everywhere. Measuring around 2x2 to 3x5 inches, and drawn or printed on paper or vinyl, stickers are usually made individually by hand or in small batches through cheap online printing services.

In bigger cities, stickers can be found "hidden in plain sight," slapped up on signposts, light fixtures, and every other imaginable surface of the built environment. On college campuses, stickers cover bulletin boards and bathroom stalls. At home, stickers decorate laptops and skate decks.

In the United States and around the world, stickers are used to advertise the latest streetwear, hip-hop bands, or social media sites. Some artists make stickers to "tag" a space and claim it, at least temporarily, as one's own, though nowadays many American cities have pretty active anti-graffiti laws in place. Stickers also carry socio-political messages that ebb and flow over time and space, depending on who is in office or what issues are playing out in the government or on Wall Street.

But wait. Street art stickers? In a college classroom on Spanish literature and culture?

On a cold autumn afternoon at St. Lawrence University's art gallery in Canton, New York, fourteen undergraduate students sit in a semi-circle on a rug, visiting as part of Professor Marina Llorente's class on Literature, Film and Popular Culture in Contemporary Spain. Some are leaning up against walls, a few others splayed out on beanbag chairs strewn across the floor. They're not here to talk about the current exhibition on display. Rather, everyone is poring over street art stickers from Madrid, Catalonia, Asturias, Galicia, and elsewhere in Spain. Some are new, sent from artists, political organizations, and colleagues who knew about the course project. Other stickers are old, torn, gritty. The students touch them. Smell them. Look at them, realizing they once inhabited a difference space. Everyone is curious to know, to understand, to make sense of messages still infused with the polluted air of a city, the dirt on the walls, the honking of car horns, and the eyes that once glanced at and ingested these messages on the streets of Spain's cities.

![2015-03-01-16448675287_09a3433e9b_q.jpg]()

Photo by Tara Freeman: Adilson Gonzalez Morales, SLU '16,

with street art stickers from Catalonia.

Why are the students so stuck on the sight of these stickers? Because flashing before their eyes are artistic sound bites of something much larger: political agendas, cultural idiosyncrasies, or economic realities that speak about the Catalonian separatist movement, worker's rights, the environment, gender or sexuality, and other issues. Some stickers shout; others whisper. One from 2003 calls for a General Strike and No a la Guerra or "No to war" in Iraq. In the background, a picture of Picasso's Guernica reminds Spaniards of their country's violent past under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

![2015-03-01-14939849533_f5ba266800_z.jpg]()

Reproduced with permission from the St. Lawrence University Art Gallery.

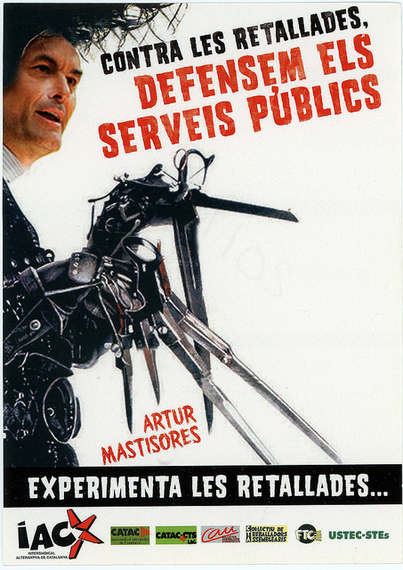

A more recent sticker shows the contemporary Catalan politician Arthur Mas dressed as a dark Gothic Edward Scissorhands with Contra les retallades, Defensem els serveis públics, or "Against the Cuts, Defend Public Services." A third small sticker presents a simple drawing of a crown covered by a red circle with a line through it, the universal No symbol, referencing opposition to the Spanish monarchy.

Students excitedly begin to investigate and synthesize the clues, using their linguistic skills, their visual and textual analytical skills, their background knowledge in the history and politics of the Basque Country or of Catalonia, and their cultural understanding and ability to put messages and ideas into context.

Students unstick these stickers from the walls, cars, and containers to which they previously adhered, and in a different time and place, here in northern New York at this small Liberal Arts college, they begin to listen and learn as the streets begin to talk.

You might not have observed what is called "street art stickers" before, but once you do, you'll start seeing them everywhere. Measuring around 2x2 to 3x5 inches, and drawn or printed on paper or vinyl, stickers are usually made individually by hand or in small batches through cheap online printing services.

In bigger cities, stickers can be found "hidden in plain sight," slapped up on signposts, light fixtures, and every other imaginable surface of the built environment. On college campuses, stickers cover bulletin boards and bathroom stalls. At home, stickers decorate laptops and skate decks.

In the United States and around the world, stickers are used to advertise the latest streetwear, hip-hop bands, or social media sites. Some artists make stickers to "tag" a space and claim it, at least temporarily, as one's own, though nowadays many American cities have pretty active anti-graffiti laws in place. Stickers also carry socio-political messages that ebb and flow over time and space, depending on who is in office or what issues are playing out in the government or on Wall Street.

But wait. Street art stickers? In a college classroom on Spanish literature and culture?

On a cold autumn afternoon at St. Lawrence University's art gallery in Canton, New York, fourteen undergraduate students sit in a semi-circle on a rug, visiting as part of Professor Marina Llorente's class on Literature, Film and Popular Culture in Contemporary Spain. Some are leaning up against walls, a few others splayed out on beanbag chairs strewn across the floor. They're not here to talk about the current exhibition on display. Rather, everyone is poring over street art stickers from Madrid, Catalonia, Asturias, Galicia, and elsewhere in Spain. Some are new, sent from artists, political organizations, and colleagues who knew about the course project. Other stickers are old, torn, gritty. The students touch them. Smell them. Look at them, realizing they once inhabited a difference space. Everyone is curious to know, to understand, to make sense of messages still infused with the polluted air of a city, the dirt on the walls, the honking of car horns, and the eyes that once glanced at and ingested these messages on the streets of Spain's cities.

Photo by Tara Freeman: Adilson Gonzalez Morales, SLU '16,

with street art stickers from Catalonia.

Why are the students so stuck on the sight of these stickers? Because flashing before their eyes are artistic sound bites of something much larger: political agendas, cultural idiosyncrasies, or economic realities that speak about the Catalonian separatist movement, worker's rights, the environment, gender or sexuality, and other issues. Some stickers shout; others whisper. One from 2003 calls for a General Strike and No a la Guerra or "No to war" in Iraq. In the background, a picture of Picasso's Guernica reminds Spaniards of their country's violent past under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

Reproduced with permission from the St. Lawrence University Art Gallery.

A more recent sticker shows the contemporary Catalan politician Arthur Mas dressed as a dark Gothic Edward Scissorhands with Contra les retallades, Defensem els serveis públics, or "Against the Cuts, Defend Public Services." A third small sticker presents a simple drawing of a crown covered by a red circle with a line through it, the universal No symbol, referencing opposition to the Spanish monarchy.

Students excitedly begin to investigate and synthesize the clues, using their linguistic skills, their visual and textual analytical skills, their background knowledge in the history and politics of the Basque Country or of Catalonia, and their cultural understanding and ability to put messages and ideas into context.

Students unstick these stickers from the walls, cars, and containers to which they previously adhered, and in a different time and place, here in northern New York at this small Liberal Arts college, they begin to listen and learn as the streets begin to talk.