"If I had my way, I wouldn't put in dogs, but wolves," New York mayor Ed Koch suggested famously as a facetious proposal for releasing ferocious animals on graffiti writers in the train yards in the early 1980s. For Koch and his two predecessors the graffiti on trains was a searingly hot focal point, a visual affront to citizens, an aesthetic plague upon the populous. It created a discomforting atmosphere described by The New York Times editorial board as evidence of "criminality and contempt for the public."* The fight against this particular blight began in earnest, and by decade's end all 5,000 or so subway cars had become clean and the famed era of graffiti on trains was terminated.

Twenty-five years later, whole-car graffiti trains are back in New York. Visually bombed with color and stylized typography top to bottom, inside and outside, and the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) is pocketing some handsome fees for it. It is not aerosol anymore, rather the eye-popping subway skin is made from enormous adhesive printed sheets that are laser cut to perfectly fit every single surface of a train car. Naturally, you won't have to pay the newly hiked subway fare to see these whole-car creations -- you can see them on elevated tracks all over the city.

![2015-02-12-brooklynstreetartsubwaygraffiitijaimerojo0215web1.jpg]()

Photo © Jaime Rojo

The irony doesn't stop there: Right now the MTA is running a full-car advertisement for a "Street Art" series that appears on cable, featuring images of fleet-footed youth with art supplies in hand running down a Brooklyn sidewalk as if escaping from the police. "Run. Paint."

"Of course I chuckle every time I see those ad-covered cars," says Martha Cooper, the ethnographer and photographer perhaps best known for shooting images of artists like Lee Quinones and Dondi as they painted huge pieces in the train yards in the 1970s and 80s. Together with Henry Chalfant, Cooper published what became a photographic holy book for generations of graff writers and street artists worldwide, a compendium of full-car aerosol painted pieces from New York's graffiti train era entitled Subway Art. When it comes to using trains for advertising, Cooper doesn't appear offended, but rather gives credit for the idea to the youth who pioneered the technique of using trains as a self-promotional method, and she's only puzzled about why this didn't happen earlier.

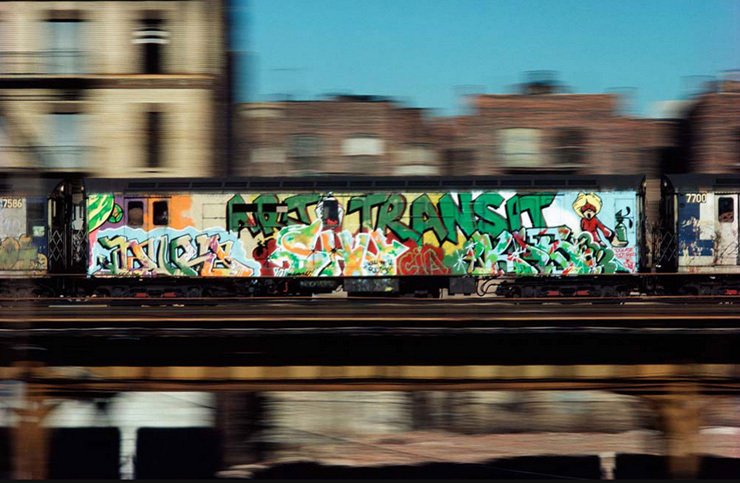

![2015-02-12-BrooklynStreetArt740copyrightMarthaCooperArtvstransit1982.jpg]()

Art vs. Transit (the "vs." already scrubbed off the window), by Duro, Shy and Kos 207. 1982. © Martha Cooper

"Graffiti writers instinctively understood how advertising could reach the most people in NYC," she says, "It's taken 45 years for the MTA and ad agencies to realize what a good idea top-to-bottom rolling ads are, on trucks as well as on the subway. They are finally catching on and catching up but they would probably be the last to admit it. The rest of us can just stand back and shake our heads in amusement."

But some others are less ready to accept the irony of a street art program being promoted on train cars, including guys who were those same vilified/celebrated teens painting trains at a time when penalties were harsh and the dogs were real.

![2015-02-12-brooklynstreetartsubwaygraffiitijaimerojo0215web31.jpg]()

Photo © Jaime Rojo

"What a complete bite and contradiction on the MTA's part," says artist Lee Quiñones, perhaps best known for having painted as many as 125 entire cars by hand in the 1970s, as well as a more formal art career that followed. His fully painted cars as canvasses included characters, scenes, and narratives addressing topical subjects like the crime rate, the cold war, poverty, and environmentalism -- as well as more existential teen poetry about love and family. For Quiñones, who once called the #5 subway line the "Rolling MoMA," and who today is a fine artist with a successful studio practice, the paradox is obvious. "It exposes how certain things under the guidance of capital can be blatantly suggested and ingested within the same context."

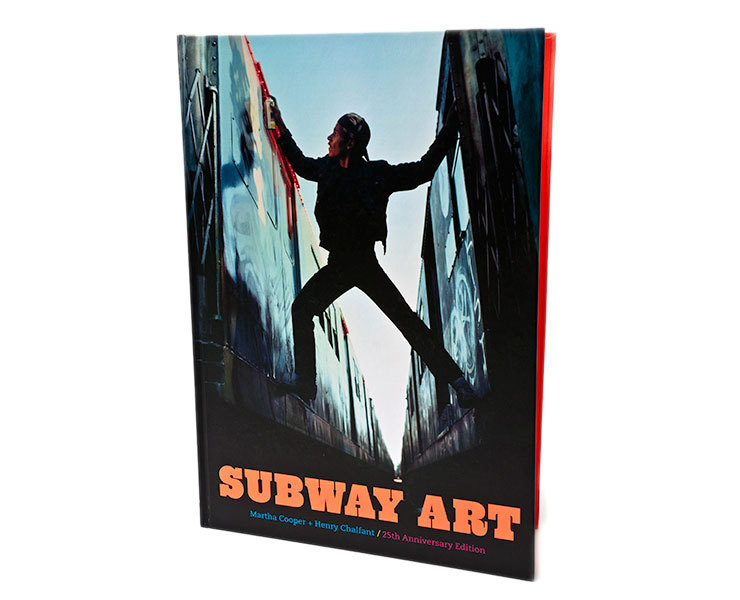

Jayson Edlin, author of Graffiti 365, is considered by many as a go-to source for New York graffiti and its history, and was himself a train writer under the names J.Son and Terror 161. "The advertising versus art argument regarding graffiti and street art speaks to money, power and control. Societal hypocrisy is nothing new. As a former subway painter, I am not surprised by seeing an ad for a street art TV show plastered across a NYC subway car," he says. Then he pitches us a vision that would undoubtedly make many people's brain hurt. "I'm certain that the MTA would sanction an ad for Subway Art with the Marty Cooper photo of Dondi painting a train for the right sum." Imagine what that might look like.

![2015-02-12-BrooklynStreetArt740SubwayArtCoverCooperChalfant.jpg]()

Now, the MTA would not wish you to think they are endorsing illegal graffiti or street art, according to an MTA spokesperson recently interviewed by Bucky Turco for the website Animal. The MTA walked a thin line when determining whether they should accept advertising for a show celebrating street art, however contrived, and decided that it was okay to take the money this time. "On the one hand," says the spokesman, "our ad standards prohibit anything that could be construed as actual graffiti, and we also prohibit promoting illegal activity. On the other hand, the typeface of the ad itself was not graffiti-style, and our research concluded that everything the show depicts is done legally with permission." So we'll take the MTA at its word, the show doesn't explicitly violate standards for advertising, so the campaign was approved.

![2015-02-12-brooklynstreetartsubwaygraffiitijaimerojo0215web2.jpg]()

Photo © Jaime Rojo

It's true, not all street art is illegal per se, but by definition most people would say that real graffiti must be. However it may take a lawyer to explain how this rationalization of advertising a show like this works, or at least to help sort the legalities from the ethics and perceptions. So, to recap, decades ago it was a crime to write graffiti on the subways. Today if you have enough money and the right hand-style with your lettering you can use your creativity to mark up as many cars as you like. If not, your art-making efforts will be swiftly eradicated. This past year photographer Jaime Rojo just happened to catch some non-commercial art on trains that pulled into stations and he said it was just as surprising to see the real stuff as it is the commercial facsimile of it. Of course the D.I.Y. never made it out of the train yards again.

![2015-02-12-brooklynstreetartdvonejaimerojo0515web3.jpg]()

Actual graffiti on a New York train from DVONE, circa 2014. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

Alison Young, Professor of Criminology at the University of Melbourne in Australia and author of Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination has studied the interaction of art, advertising, and the law specifically as it pertains to street art around the world. She points to a radical difference in how these two forms of visual communication are regarded and approached. "The full-car advertisement for the television program is certainly the most obvious demonstration of how companies (such as the MTA) respond differently to advertising than to street art/graffiti."

"In some ways," Young continues, "the MTA may not even have noticed the irony of covering a train car with an advert for an activity related to graffiti, given the time and money spent on eradicating images from train cars. Or, if I was being really cynical, it's also possible to speculate that the MTA sees that irony all too clearly and is using this as an opportunity to tell graffiti writers that unsanctioned art is never acceptable, but sanctioned art (in the form of an advert or in the form of the art featured on the show) is all that we are permitted to see. Is that too unlikely? I don't know."

![2015-02-12-brooklynstreetartdvonejaimerojo0515web4.jpg]()

DVONE. Graffiti circa 2014. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

A number of folks whom we talked to mentioned that this is not the first time a graffiti artist has completely covered subway cars with advertisements, as the artist KAWS was treated to a full campaign when he partnered with Macy's a couple of years ago. While he has had a successful commercial career with fine art, toys and a variety of products, his roots are as a graffiti writer. He has done some freight painting of his own, and his style still reflects it. Not every impressionable disaffected youth would necessarily make that association nor interpret it as an encouragement to hit up a train with your own aerosol bubble tag. Still, those KAWS cars looked a lot like graffiti trains, with logos as tags, as seen in this video from Fresh Paint NYC.

We leave the last observations to the witty and insightful Dr. Rafael Schacter, anthropologist, curator, and author of The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti, who says the obvious story is, well, obvious, but don't miss the elephant in the subway car.

"The irony and incongruity of it though? Of course. It is ridiculous. It is absurd. A graffiti-banning MTA promoting a graffiti TV show and allowing a second-rate aping of the original whole-trains of the '70s," he says derisively. But then he turns frank and even wistful in his final summary.

"But, in actual fact, I LOVE these moments. I love them as they so perfectly illustrate the public secret of our public sphere: That consumption wins. That the highest bidder is the true King. It's nothing new. It's nothing surprising but it is the revelation of the public secret that can actually come to raise awareness of that secret itself -- that the public sphere has come to be a space not for conversation but for commerce. That the public sphere has become a place not for interpersonal communication but for capital and consumption," says Schacter.

"These moments can, I hope, make us sit up and realize this revelation because it is thrown so directly in our faces. Then, hopefully, this can make us make a change. Perhaps a tiny bit of a rose-tinted position to take, but I really do hope so."

Rose-tinted views will probably overruled by the green-tinted ones in this case, but we understand the sentiment. But many New York subway riders will not likely soon get over the irony.

![2015-02-12-brooklynstreetartmarveljaimerojo0515web2.jpg]()

Marvel graffiti circa 2014. (photo © Jaime Rojo)

<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><>

*Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, Jonathan M. Soffer.

<><><><><><><><><><><><><>

This article is also posted on Brooklyn Street Art.

Read all posts by Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo on The Huffington Post HERE.

See new photos and read scintillating interviews every day on BrooklynStreetArt.com

Follow us on Instagram @bkstreetart

See our TUMBLR page

Follow us on TWITTER @bkstreetart

Twenty-five years later, whole-car graffiti trains are back in New York. Visually bombed with color and stylized typography top to bottom, inside and outside, and the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) is pocketing some handsome fees for it. It is not aerosol anymore, rather the eye-popping subway skin is made from enormous adhesive printed sheets that are laser cut to perfectly fit every single surface of a train car. Naturally, you won't have to pay the newly hiked subway fare to see these whole-car creations -- you can see them on elevated tracks all over the city.

The irony doesn't stop there: Right now the MTA is running a full-car advertisement for a "Street Art" series that appears on cable, featuring images of fleet-footed youth with art supplies in hand running down a Brooklyn sidewalk as if escaping from the police. "Run. Paint."

"Of course I chuckle every time I see those ad-covered cars," says Martha Cooper, the ethnographer and photographer perhaps best known for shooting images of artists like Lee Quinones and Dondi as they painted huge pieces in the train yards in the 1970s and 80s. Together with Henry Chalfant, Cooper published what became a photographic holy book for generations of graff writers and street artists worldwide, a compendium of full-car aerosol painted pieces from New York's graffiti train era entitled Subway Art. When it comes to using trains for advertising, Cooper doesn't appear offended, but rather gives credit for the idea to the youth who pioneered the technique of using trains as a self-promotional method, and she's only puzzled about why this didn't happen earlier.

"Graffiti writers instinctively understood how advertising could reach the most people in NYC," she says, "It's taken 45 years for the MTA and ad agencies to realize what a good idea top-to-bottom rolling ads are, on trucks as well as on the subway. They are finally catching on and catching up but they would probably be the last to admit it. The rest of us can just stand back and shake our heads in amusement."

But some others are less ready to accept the irony of a street art program being promoted on train cars, including guys who were those same vilified/celebrated teens painting trains at a time when penalties were harsh and the dogs were real.

"What a complete bite and contradiction on the MTA's part," says artist Lee Quiñones, perhaps best known for having painted as many as 125 entire cars by hand in the 1970s, as well as a more formal art career that followed. His fully painted cars as canvasses included characters, scenes, and narratives addressing topical subjects like the crime rate, the cold war, poverty, and environmentalism -- as well as more existential teen poetry about love and family. For Quiñones, who once called the #5 subway line the "Rolling MoMA," and who today is a fine artist with a successful studio practice, the paradox is obvious. "It exposes how certain things under the guidance of capital can be blatantly suggested and ingested within the same context."

Jayson Edlin, author of Graffiti 365, is considered by many as a go-to source for New York graffiti and its history, and was himself a train writer under the names J.Son and Terror 161. "The advertising versus art argument regarding graffiti and street art speaks to money, power and control. Societal hypocrisy is nothing new. As a former subway painter, I am not surprised by seeing an ad for a street art TV show plastered across a NYC subway car," he says. Then he pitches us a vision that would undoubtedly make many people's brain hurt. "I'm certain that the MTA would sanction an ad for Subway Art with the Marty Cooper photo of Dondi painting a train for the right sum." Imagine what that might look like.

Now, the MTA would not wish you to think they are endorsing illegal graffiti or street art, according to an MTA spokesperson recently interviewed by Bucky Turco for the website Animal. The MTA walked a thin line when determining whether they should accept advertising for a show celebrating street art, however contrived, and decided that it was okay to take the money this time. "On the one hand," says the spokesman, "our ad standards prohibit anything that could be construed as actual graffiti, and we also prohibit promoting illegal activity. On the other hand, the typeface of the ad itself was not graffiti-style, and our research concluded that everything the show depicts is done legally with permission." So we'll take the MTA at its word, the show doesn't explicitly violate standards for advertising, so the campaign was approved.

It's true, not all street art is illegal per se, but by definition most people would say that real graffiti must be. However it may take a lawyer to explain how this rationalization of advertising a show like this works, or at least to help sort the legalities from the ethics and perceptions. So, to recap, decades ago it was a crime to write graffiti on the subways. Today if you have enough money and the right hand-style with your lettering you can use your creativity to mark up as many cars as you like. If not, your art-making efforts will be swiftly eradicated. This past year photographer Jaime Rojo just happened to catch some non-commercial art on trains that pulled into stations and he said it was just as surprising to see the real stuff as it is the commercial facsimile of it. Of course the D.I.Y. never made it out of the train yards again.

Alison Young, Professor of Criminology at the University of Melbourne in Australia and author of Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination has studied the interaction of art, advertising, and the law specifically as it pertains to street art around the world. She points to a radical difference in how these two forms of visual communication are regarded and approached. "The full-car advertisement for the television program is certainly the most obvious demonstration of how companies (such as the MTA) respond differently to advertising than to street art/graffiti."

"In some ways," Young continues, "the MTA may not even have noticed the irony of covering a train car with an advert for an activity related to graffiti, given the time and money spent on eradicating images from train cars. Or, if I was being really cynical, it's also possible to speculate that the MTA sees that irony all too clearly and is using this as an opportunity to tell graffiti writers that unsanctioned art is never acceptable, but sanctioned art (in the form of an advert or in the form of the art featured on the show) is all that we are permitted to see. Is that too unlikely? I don't know."

A number of folks whom we talked to mentioned that this is not the first time a graffiti artist has completely covered subway cars with advertisements, as the artist KAWS was treated to a full campaign when he partnered with Macy's a couple of years ago. While he has had a successful commercial career with fine art, toys and a variety of products, his roots are as a graffiti writer. He has done some freight painting of his own, and his style still reflects it. Not every impressionable disaffected youth would necessarily make that association nor interpret it as an encouragement to hit up a train with your own aerosol bubble tag. Still, those KAWS cars looked a lot like graffiti trains, with logos as tags, as seen in this video from Fresh Paint NYC.

We leave the last observations to the witty and insightful Dr. Rafael Schacter, anthropologist, curator, and author of The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti, who says the obvious story is, well, obvious, but don't miss the elephant in the subway car.

"The irony and incongruity of it though? Of course. It is ridiculous. It is absurd. A graffiti-banning MTA promoting a graffiti TV show and allowing a second-rate aping of the original whole-trains of the '70s," he says derisively. But then he turns frank and even wistful in his final summary.

"But, in actual fact, I LOVE these moments. I love them as they so perfectly illustrate the public secret of our public sphere: That consumption wins. That the highest bidder is the true King. It's nothing new. It's nothing surprising but it is the revelation of the public secret that can actually come to raise awareness of that secret itself -- that the public sphere has come to be a space not for conversation but for commerce. That the public sphere has become a place not for interpersonal communication but for capital and consumption," says Schacter.

"These moments can, I hope, make us sit up and realize this revelation because it is thrown so directly in our faces. Then, hopefully, this can make us make a change. Perhaps a tiny bit of a rose-tinted position to take, but I really do hope so."

Rose-tinted views will probably overruled by the green-tinted ones in this case, but we understand the sentiment. But many New York subway riders will not likely soon get over the irony.

<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><>

*Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, Jonathan M. Soffer.

<><><><><><><><><><><><><>

This article is also posted on Brooklyn Street Art.

Read all posts by Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo on The Huffington Post HERE.

See new photos and read scintillating interviews every day on BrooklynStreetArt.com

Follow us on Instagram @bkstreetart

See our TUMBLR page

Follow us on TWITTER @bkstreetart