When I recently visited the impressive Marc Chagall exhibit at the Jewish Museum in New York City, I was surprised that more than half of the 31 paintings include a crucifixion theme. More surprising, the dying Jesus is clearly a Jew, frequently shown wearing a Jewish prayer shawl rather than a plain loin cloth. For Chagall, the crucifixion represented the common ground of suffering of Christians and Jews. In reminding us of Jesus' Jewish identity Chagall departed from the massive numbers of artworks that have falsely pictured Jesus as strictly Christian, thus fueling the historic rift between Christians and Jews.

"Do you know that Jesus was Jewish?" I posed this question to both Christians and Jews when I was doing research for my book Jesus Uncensored: Restoring the Authentic Jew. Many people acknowledged that Jesus was indeed Jewish. But I discovered that what they really meant was that he used to be Jewish -- before he became Christian.

"Of course, he was Jewish," said Jane, a young woman educated in Catholic schools. "And did he remain Jewish throughout his life?" I asked her. "Oh, no, he became a Christian." "When did that happen?" I asked. "When he was baptized by John the Baptist," she said. "It says so in the Gospels."

Scores of other people I talked to gave similar responses. Some even contended that Jesus was born Christian or that he launched the new religion of Christianity. The Gospels make it clear that Jesus and his family were dedicated Jews throughout their lives. Bible scholars do not dispute this. For example, in his book Rabbi Jesus, Episcopal priest Bruce Chilton says: "It became clear to me that everything Jesus did was as a Jew, for Jews, and about Jews." In fact, the well-documented but often ignored truth is that there was no such thing as Christianity during the life of Jesus. The term "Christian" never appears in the Gospels, while the term "Jew" has 82 mentions. Nor is there any evidence that Jesus envisioned or started a new religion.

But these realities seem to have eluded the artists of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Consider Bartolomé Esteban Murillo's 17th century painting of John the Baptist baptizing Jesus (The Baptism of Christ). The baptism here is clearly a Christian conversion. But according to the Gospels, John only baptized Jews, and he did so to purify them for the expected coming of the prophesized Jewish Messiah. Yet Murillo's painting shows John holding a crucifix staff -- a Christian symbol that wouldn't come into being until three centuries later. In fact, the cross was a hated symbol in the time of Jesus.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Baptism of Christ by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Murillo's painting is not alone. In my walking tour of the Renaissance galleries of New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art, I encountered painting after painting that omitted Jesus' true identity. In the bulk of Medieval and Renaissance artworks, Jesus, his family, and close followers are converted into latter-day Christians. They are typically depicted as blond, fair-skinned northern European Christians. Reinforcing that misrepresentation, many of the paintings include anachronistic Christian saints and artifacts. Other paintings in art books about the Medieval and Renaissance periods, such as Gospel Figures in Art, show the same falsifications.

In defense of artists, art was a tough competitive business in Renaissance Italy. One art critic characterized it as "no picnic." If you wanted to stay in business you had to give your wealthy patrons what they wanted -- and that meant totally Christianized artworks. Whether deliberate, inadvertent, or both, the omissions still add up to pernicious falsifications of biblical history with divisive consequences that still reverberate today.

But tell art historians and even lay people who are interested in art that artworks depicting Jesus (and his family and close followers) falsify biblical history, and you can expect a dismissive response, or even a condescending smirk, suggesting you are ignorant or naïve. I've experienced that many times. These experts maintain that contemporizing -- depicting figures in Renaissance settings, attire, and appearance -- is typical of the "Renaissance style." For these experts, the "style" mantra has become an unexamined response that closes the book on the story.

But contemporizing biblical figures is not the end of the story. It's the starting point of a gross misunderstanding. Contemporizing -- and fashioning in your own image -- is one thing, but erasing identities is another matter, a serious matter with serious consequences. In the case of these art misrepresentations, falsification is an overlooked but powerful underpinning of historic anti-Semitism. In presenting Jesus as a Renaissance Christian with no Jewish connection or identity, these works created the illusion that Jesus and Jews were not only of different ethnicities and religions but that they were in opposition or conflict. Punctuating this point, paintings like Albrecht Durer's 16th century Jesus among the Doctors (based on an episode in the Gospel of Luke 2:41-52), picture the Jews, not as blond northern Europeans, but as menacing and ugly figures. The reddish-blond delicate and ethereal Jesus stands in stark contrast.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-01-12-ALbrechtDurerChristamongthedoctors2.jpg]()

Christ Among the Doctors (scholars-rabbis) by Albrecht Durer

Although African and other artists have depicted a black Jesus -- representations probably closer to Jesus' actual appearance than the Northern Renaissance blond renditions -- they still omit the Jewish connection, thereby also contributing to falsification.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-01-12-BlackMadonnaandJesusofEinsiedeln3.jpg]()

Black Madonna and Child of Einsiedeln

In inventing a rift between Jesus and Jews these artworks widened the divide between Christianity and Judaism -- a divide that has only recently begun to close. This past year, in the spirit of reconciliation, Pope Francis said: "It's a contradiction for a Christian to be anti-Semitic: His roots are Jewish."

The art exhibit that I'm organizing, "Putting Judaism Back in the Picture: Toward Healing the Christian/Jewish Divide," will correct the art distortions with redrawn and other original works that tell the two sides of the Jesus story: Jesus the faithful Jew and Jesus whose life and teachings inspired a new religion. For example, Rod Borghese's version of Murillo's The Baptism of Christ shows Jesus and John as Jews.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-01-12-RodBorgheseTheBaptismofChristwater2.jpg]()

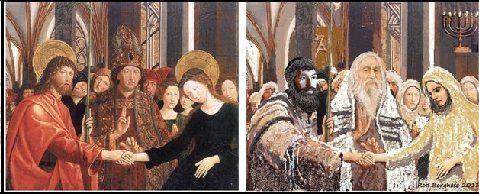

And his rendition of Michael Pacher's 15th century painting, The Betrothal of the Virgin, pictures Mary and Joseph as the rural village Jews that they were, not as regal figures in a palatial setting with a high Christian church official performing the ceremony.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-01-12-RodBorgheseBetrothaloftheVirgin3.jpg]()

It's time for scholars to acknowledge how the historical distortions in biblical depictions have contributed to anti-Semitism and to the false divide between Jews and Christians. It's time for art historians to start telling the truth about the falsification of biblical history. The truth will take nothing away from the magnificence of the artworks, but it will contribute substantially to authenticity and the healing of long-standing wrongs and wounds.

Note: Rod Borghese, an architect and painter in Ottawa, Canada, who has joined the art exhibit, along with other talented artists, is a distant descendant of the Italian Renaissance banking family that commissioned many paintings and collected a large body of others. Today, the famed Borghese Gallery in Rome houses one of the world's great art collections.

Bernard Starr is a college professor, psychologist and journalist. He is author of Jesus Uncensored: Restoring the Authentic Jew. For more information about the Art Exhibit visit www.JewishJesusartexhibit.com

"Do you know that Jesus was Jewish?" I posed this question to both Christians and Jews when I was doing research for my book Jesus Uncensored: Restoring the Authentic Jew. Many people acknowledged that Jesus was indeed Jewish. But I discovered that what they really meant was that he used to be Jewish -- before he became Christian.

"Of course, he was Jewish," said Jane, a young woman educated in Catholic schools. "And did he remain Jewish throughout his life?" I asked her. "Oh, no, he became a Christian." "When did that happen?" I asked. "When he was baptized by John the Baptist," she said. "It says so in the Gospels."

Scores of other people I talked to gave similar responses. Some even contended that Jesus was born Christian or that he launched the new religion of Christianity. The Gospels make it clear that Jesus and his family were dedicated Jews throughout their lives. Bible scholars do not dispute this. For example, in his book Rabbi Jesus, Episcopal priest Bruce Chilton says: "It became clear to me that everything Jesus did was as a Jew, for Jews, and about Jews." In fact, the well-documented but often ignored truth is that there was no such thing as Christianity during the life of Jesus. The term "Christian" never appears in the Gospels, while the term "Jew" has 82 mentions. Nor is there any evidence that Jesus envisioned or started a new religion.

But these realities seem to have eluded the artists of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Consider Bartolomé Esteban Murillo's 17th century painting of John the Baptist baptizing Jesus (The Baptism of Christ). The baptism here is clearly a Christian conversion. But according to the Gospels, John only baptized Jews, and he did so to purify them for the expected coming of the prophesized Jewish Messiah. Yet Murillo's painting shows John holding a crucifix staff -- a Christian symbol that wouldn't come into being until three centuries later. In fact, the cross was a hated symbol in the time of Jesus.

Clik here to view.

Murillo's painting is not alone. In my walking tour of the Renaissance galleries of New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art, I encountered painting after painting that omitted Jesus' true identity. In the bulk of Medieval and Renaissance artworks, Jesus, his family, and close followers are converted into latter-day Christians. They are typically depicted as blond, fair-skinned northern European Christians. Reinforcing that misrepresentation, many of the paintings include anachronistic Christian saints and artifacts. Other paintings in art books about the Medieval and Renaissance periods, such as Gospel Figures in Art, show the same falsifications.

In defense of artists, art was a tough competitive business in Renaissance Italy. One art critic characterized it as "no picnic." If you wanted to stay in business you had to give your wealthy patrons what they wanted -- and that meant totally Christianized artworks. Whether deliberate, inadvertent, or both, the omissions still add up to pernicious falsifications of biblical history with divisive consequences that still reverberate today.

But tell art historians and even lay people who are interested in art that artworks depicting Jesus (and his family and close followers) falsify biblical history, and you can expect a dismissive response, or even a condescending smirk, suggesting you are ignorant or naïve. I've experienced that many times. These experts maintain that contemporizing -- depicting figures in Renaissance settings, attire, and appearance -- is typical of the "Renaissance style." For these experts, the "style" mantra has become an unexamined response that closes the book on the story.

But contemporizing biblical figures is not the end of the story. It's the starting point of a gross misunderstanding. Contemporizing -- and fashioning in your own image -- is one thing, but erasing identities is another matter, a serious matter with serious consequences. In the case of these art misrepresentations, falsification is an overlooked but powerful underpinning of historic anti-Semitism. In presenting Jesus as a Renaissance Christian with no Jewish connection or identity, these works created the illusion that Jesus and Jews were not only of different ethnicities and religions but that they were in opposition or conflict. Punctuating this point, paintings like Albrecht Durer's 16th century Jesus among the Doctors (based on an episode in the Gospel of Luke 2:41-52), picture the Jews, not as blond northern Europeans, but as menacing and ugly figures. The reddish-blond delicate and ethereal Jesus stands in stark contrast.

Clik here to view.

Although African and other artists have depicted a black Jesus -- representations probably closer to Jesus' actual appearance than the Northern Renaissance blond renditions -- they still omit the Jewish connection, thereby also contributing to falsification.

Clik here to view.

In inventing a rift between Jesus and Jews these artworks widened the divide between Christianity and Judaism -- a divide that has only recently begun to close. This past year, in the spirit of reconciliation, Pope Francis said: "It's a contradiction for a Christian to be anti-Semitic: His roots are Jewish."

The art exhibit that I'm organizing, "Putting Judaism Back in the Picture: Toward Healing the Christian/Jewish Divide," will correct the art distortions with redrawn and other original works that tell the two sides of the Jesus story: Jesus the faithful Jew and Jesus whose life and teachings inspired a new religion. For example, Rod Borghese's version of Murillo's The Baptism of Christ shows Jesus and John as Jews.

Clik here to view.

And his rendition of Michael Pacher's 15th century painting, The Betrothal of the Virgin, pictures Mary and Joseph as the rural village Jews that they were, not as regal figures in a palatial setting with a high Christian church official performing the ceremony.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

It's time for scholars to acknowledge how the historical distortions in biblical depictions have contributed to anti-Semitism and to the false divide between Jews and Christians. It's time for art historians to start telling the truth about the falsification of biblical history. The truth will take nothing away from the magnificence of the artworks, but it will contribute substantially to authenticity and the healing of long-standing wrongs and wounds.

Note: Rod Borghese, an architect and painter in Ottawa, Canada, who has joined the art exhibit, along with other talented artists, is a distant descendant of the Italian Renaissance banking family that commissioned many paintings and collected a large body of others. Today, the famed Borghese Gallery in Rome houses one of the world's great art collections.

Bernard Starr is a college professor, psychologist and journalist. He is author of Jesus Uncensored: Restoring the Authentic Jew. For more information about the Art Exhibit visit www.JewishJesusartexhibit.com