My first visit was too frightening to bring a camera bag. A murky river of uncertain depth left the doorstep of my destination, the African Artists' Foundation (AAF), nine feet out of reach. After pacing up and down the dusty Lagos road, a single plywood plank strewn across the moat seemed precarious at best. Already late due to a "go slow," a local term for the incessant traffic, I left my gear with my driver, swallowed my fear of heights and baby-stepped my way across wobbling wood.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Entrance to Nigeria's African Artists' Foundation. Also home to LagosPhoto, images from around the globe adorn interior and exterior walls. All images © Ruthie Abel 2014

AAF was a first stop in a ten-day foray into Nigerian contemporary art. The trip focused on Lagos, Africa's most populous city (estimated 21 million people, outpacing Cairo) and the center of contemporary creativity in Nigeria. A sprawling port on the Atlantic, Lagos is hundreds of miles south of the regions where over 200 schoolgirls remain kidnapped and the sites of the most recent Boko Haram bombings. While somewhat distanced from the country's worst violence, with daily power cuts and nearly half of the population living below the national poverty line, Lagos is by no means a simple place to make or experience art.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Laundry and satellite dishes spill onto the Lagos international airport runway. Burgeoning population density and paltry infrastructure makes searching for art venues a needle-in-haystack expedition. © Ruthie Abel 2014

There are no art museums in Nigeria. A handful of overstocked gallerias and arts organizations are the only publicly accessible venues dedicated to viewing art. Typically adjacent to a hotel or restaurant or tucked into a residential complex, arts spaces are challenging to locate, climate-controlled environments are non-existent and works are tormented in turns by dust storms and excessive humidity.

Yet there are gems to be found. Treacherous construction on AAF's doorstep conceals exhibition and workshop space as well as guest rooms and a lounge frequented by local and visiting artists, curators and writers. A mix of 20 and 30-something ex-pats and repatriated Nigerians (educated abroad, back with start-up vigor) occupy a handful of guest rooms. AAF hosts Nigeria's annual National Art Competition but the space is also home to the international Lagos Photo Festival.

Similarly hidden on a couple of floors of an unmarked building, the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) includes exhibition space and a library.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

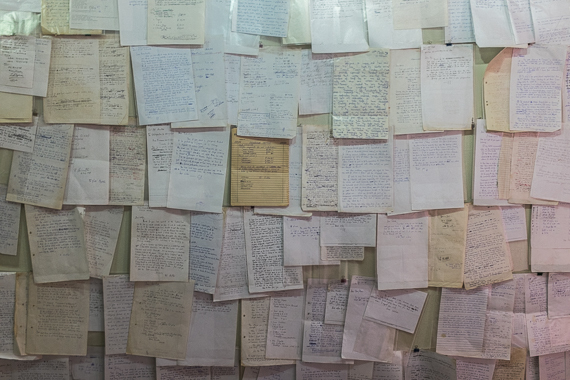

Detail of "El Anatsui: Playing with Chance," a CAA installation that includes the Nigeria-based Ghanaian artist's correspondence with curators, collectors and assistants. Perhaps most renowned for massive liquor bottle top sculptural hangings, Anatsui is a patriarch of West African contemporary art and has been working with discarded objects for half a century.

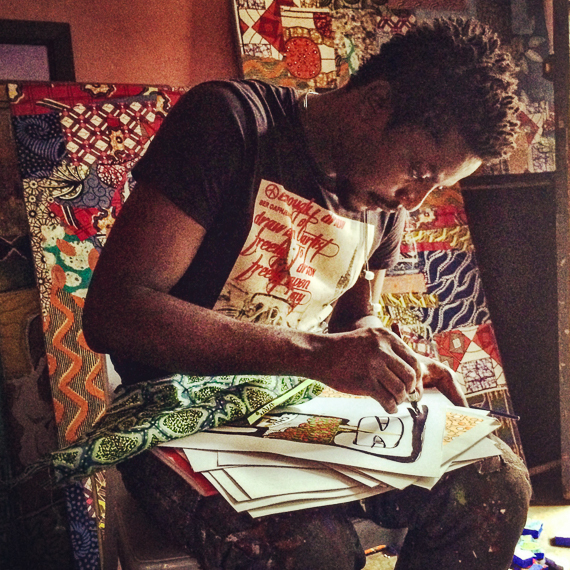

Shows at CAA and AAF led to studio visits, windows into how local creatives rise above environmental challenges. Below are images and excerpts from time with four artists, beginning with Obinna Makata, an alum of Anatsui's seminar at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka and a recent artist in residence at CAA.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. My parents are civil servants, but they supported me becoming an artist. They didn't have money to give me to set up a studio but their advice and encouragement was worth more -- I am lucky. - Obinna Makata © Ruthie Abel 2014

My parents are civil servants, but they supported me becoming an artist. They didn't have money to give me to set up a studio but their advice and encouragement was worth more -- I am lucky. - Obinna Makata © Ruthie Abel 2014

With Obinna Makata in his Lagos studio:

RA: Let's talk about the fabrics in your work.

OM: My first breakthrough as an artist was when I was so down. In 2011 I could hardly feed myself. I couldn't afford to buy materials, only pen and ink. I was just trying to keep myself busy. I had a neighbor who was a tailor and I saw scraps of fabric and thought "let me just attach it," and that's how my style began. The director of AAF saw my work in a small craft shop. I tried to explain, it wasn't even work, it was just my frustration. He made me stay with it. Five of the works at Art Twenty One sold before (a recent show) opened.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-12-26-20140404_MakatainstudioRuthieAbel_5510_001__.jpg]()

If I want to lift my spirits, I play Bob Marley. For something more subtle or romantic, Gregory Isaacs or Eric Donaldson. But Marley is just the best. - Obinna Makata © Ruthie Abel 2014

RA: What are you working on now?

OM: I have been working on issues of identity and the loss of culture of African society. Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart is a classic book on how Europeans invaded Africa and imposed their way of life. Thirty years later, things keep falling apart. When I came here for my residency I met artists from other parts of the world and I realized that loss of culture is not particular only to Africa. So I shifted my research to an issue that the cause and effect is African: excessive acquisition of material things and the implications of consuming without producing or investing money in the proper way.

There are a lot of crimes -- kidnapping and prostitution and things that make money fast. There's a trend in Nigeria now that almost all of the governors have private jets. This is money that is supposed to build infrastructure. Everything boils down to materialism and consumerism. I am using the Lagos fashion industry as a case study. Everyone is so fashion-conscious.

RA: And fabric is a metaphor for fashion?

OM: Most of these fabrics, the color and motif are African. But 80% are printed in Holland. Nigeria is one of the world's highest producers of crude oil. But we have no refineries, we rely on the west to refine it and sell it back to us.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-12-26-20140327_UcheRuthieAbel_5610_001__.jpg]()

A lot of artists preach about social issues and corruption, but Uche (Uzorka) actually lives what he preaches and his life is his work. - Makata on Uzorka (pictured) © Ruthie Abel 2014

With Uche Uzorka in his Lagos studio:

RA: How does your day begin?

UU: I wake and first thing, I hit the canvas and start cutting paper. I get consumed in the process, because for me that's joy.

RA: Those truck horns are deafening -- does the noise outside affect you?

UU: There's a lot of traffic on this road, always chaos. When I first came (to Lagos), I couldn't contain the noise. It was too loud, people talking too fast, too aggressive. But I began to imbibe all of that noise and transmit it to my canvas... I am wondering where to find a balance. I am standing between the canvas and the street and they are both noisy.

RA: What do you like to do outside of the studio?

UU: Around 5 or 6 o'clock I may go out and watch football. I find myself supporting Chelsea Football Club. You get hypnotized. Every game statistic is given to you and it is difficult to get your brain away.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-12-26-20140328_PejugardenRuthieAbel_5793_001__.jpg]()

I studied architecture because my dad didn't understand what art was about and he thought, 'There's no money to be made, it's a life of frustration, you're female, you should have a job that will make men want to marry you.' - Peju Alatise © Ruthie Abel 2014

With Peju Alatise, in her Lagos home studio:

RA: When did you transition your practice from architecture to art?

PA: For a while, I was torn between my architecture practice, design work, painting, sculpting and telling stories. It was like cooking with all of the condiments at the same time. My paintings look like sculptures and my sculptures look like paintings and they all have this long story about them and sometimes I design pieces that come with usable furniture pieces. I lacked editing in my work because I wanted to show everything in it. I wanted it to be a mini-me.

RA: What are you working on now?

PA: I took March off from the studio to write my third book. I went to South Africa and thought I would continue (in Lagos) but there's no electricity and the heat is driving me mad. I will go anywhere there's electricity! There has been a total blackout here for three months. Once in a while there's electricity for 15-30 minutes.

The queue (for generator fuel) probably takes 4 hours, you get back home with a headache that radiates down to your shoulders and armpits. You want to type but you can't think straight. You don't get anything here without a fight.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-12-26-20140328_PejuAlatisedoorwayRuthieAbel_5822_001__.jpg]()

There are certain people who make sure we don't have electricity, they are the .0001%. These are people who own the government. They just sit there and rape the country of all of its resources. - Peju Alatise © Ruthie Abel 2014

RA: How was your residency in Essaouira?

PA: Funny enough, the way I feel about Nigeria is exactly how Moroccans talked about their government. They are hard on their government but they stay because Africa is this gem of a place.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-12-26-20140402_NikeofficeRuthieAbel_6787_001__.jpg]()

Back in the day, in rural areas, you couldn't practice as an artist if you were a woman. It was unheard of. The male artists used to get Nike arrested. She broke glass ceilings for women like myself, who were born, raised, schooled and practicing in Nigeria. She was someone that gave me courage, that as a woman, the sky's the limit. She gave us permission to aim high. - Peju Alatise on Nike Davies Okundaye (pictured) © Ruthie Abel 2014

With Chief Nike Davies Okundaye, in Lagos and via telephone:

RA: You lost your mom at age 6, fled an arranged marriage at 13, survived 16 years with an abusive polygamist husband, mastered and preserved adire (traditional indigo dying). Your work is in the Smithsonian Museum and you operate Nigeria's largest art gallery as well as craft workshops in Osogbo and Lagos that double as safe havens for women and girls. Does anything hold you back?

NDO: I was never afraid of anything except politics. I never used to vote.

Politics in Nigeria is a dirty game. People are short-minded, always jealous of what women do. They will say, "Look at that woman, go and burn her house.' And then all you have worked for is gone.

RA: What made you decide to vote in elections?

NDO: I went to South Africa seven years ago. It was (a conference) organized by Clinton's wife, "Vital Voices", so women all over the world will have a voice. If they cheat me, all the other women will fight (for me). After the conference, we went to Fashola, the governor of Lagos state, and told him to put women in the cabinet. Now there are women in key positions, and the same in Ashun state. This conference made me want to vote, I voted for the first time.

RA: I understand you begin work before dawn. Will you take a break for the holidays?

NDO: All my artists come to eat Christmas dinner with me in Lagos. And I am going to Igidi for New Year's. I will make candied yam -- it makes everyone happy. In the village, people like python and monkey and bush meat for holidays. Because of Ebola now they said no more bush meat, but some people still eat it. I won't have it -- we are so scared. I will cook catfish and 'cow with a feather'. That's what people call chicken!

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![2014-12-26-20140326_NikeLagosRuthieAbel_5357_001__.jpg]()

We don't have snow but we wear white for purity, and indigo for love... Odun titun! Happy New Year! - Nike Davies Okundaye © Ruthie Abel 2014

Clik here to view.

AAF was a first stop in a ten-day foray into Nigerian contemporary art. The trip focused on Lagos, Africa's most populous city (estimated 21 million people, outpacing Cairo) and the center of contemporary creativity in Nigeria. A sprawling port on the Atlantic, Lagos is hundreds of miles south of the regions where over 200 schoolgirls remain kidnapped and the sites of the most recent Boko Haram bombings. While somewhat distanced from the country's worst violence, with daily power cuts and nearly half of the population living below the national poverty line, Lagos is by no means a simple place to make or experience art.

Clik here to view.

There are no art museums in Nigeria. A handful of overstocked gallerias and arts organizations are the only publicly accessible venues dedicated to viewing art. Typically adjacent to a hotel or restaurant or tucked into a residential complex, arts spaces are challenging to locate, climate-controlled environments are non-existent and works are tormented in turns by dust storms and excessive humidity.

Yet there are gems to be found. Treacherous construction on AAF's doorstep conceals exhibition and workshop space as well as guest rooms and a lounge frequented by local and visiting artists, curators and writers. A mix of 20 and 30-something ex-pats and repatriated Nigerians (educated abroad, back with start-up vigor) occupy a handful of guest rooms. AAF hosts Nigeria's annual National Art Competition but the space is also home to the international Lagos Photo Festival.

Similarly hidden on a couple of floors of an unmarked building, the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) includes exhibition space and a library.

Clik here to view.

Shows at CAA and AAF led to studio visits, windows into how local creatives rise above environmental challenges. Below are images and excerpts from time with four artists, beginning with Obinna Makata, an alum of Anatsui's seminar at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka and a recent artist in residence at CAA.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

My parents are civil servants, but they supported me becoming an artist. They didn't have money to give me to set up a studio but their advice and encouragement was worth more -- I am lucky. - Obinna Makata © Ruthie Abel 2014

My parents are civil servants, but they supported me becoming an artist. They didn't have money to give me to set up a studio but their advice and encouragement was worth more -- I am lucky. - Obinna Makata © Ruthie Abel 2014With Obinna Makata in his Lagos studio:

RA: Let's talk about the fabrics in your work.

OM: My first breakthrough as an artist was when I was so down. In 2011 I could hardly feed myself. I couldn't afford to buy materials, only pen and ink. I was just trying to keep myself busy. I had a neighbor who was a tailor and I saw scraps of fabric and thought "let me just attach it," and that's how my style began. The director of AAF saw my work in a small craft shop. I tried to explain, it wasn't even work, it was just my frustration. He made me stay with it. Five of the works at Art Twenty One sold before (a recent show) opened.

Clik here to view.

RA: What are you working on now?

OM: I have been working on issues of identity and the loss of culture of African society. Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart is a classic book on how Europeans invaded Africa and imposed their way of life. Thirty years later, things keep falling apart. When I came here for my residency I met artists from other parts of the world and I realized that loss of culture is not particular only to Africa. So I shifted my research to an issue that the cause and effect is African: excessive acquisition of material things and the implications of consuming without producing or investing money in the proper way.

There are a lot of crimes -- kidnapping and prostitution and things that make money fast. There's a trend in Nigeria now that almost all of the governors have private jets. This is money that is supposed to build infrastructure. Everything boils down to materialism and consumerism. I am using the Lagos fashion industry as a case study. Everyone is so fashion-conscious.

RA: And fabric is a metaphor for fashion?

OM: Most of these fabrics, the color and motif are African. But 80% are printed in Holland. Nigeria is one of the world's highest producers of crude oil. But we have no refineries, we rely on the west to refine it and sell it back to us.

Clik here to view.

With Uche Uzorka in his Lagos studio:

RA: How does your day begin?

UU: I wake and first thing, I hit the canvas and start cutting paper. I get consumed in the process, because for me that's joy.

RA: Those truck horns are deafening -- does the noise outside affect you?

UU: There's a lot of traffic on this road, always chaos. When I first came (to Lagos), I couldn't contain the noise. It was too loud, people talking too fast, too aggressive. But I began to imbibe all of that noise and transmit it to my canvas... I am wondering where to find a balance. I am standing between the canvas and the street and they are both noisy.

RA: What do you like to do outside of the studio?

UU: Around 5 or 6 o'clock I may go out and watch football. I find myself supporting Chelsea Football Club. You get hypnotized. Every game statistic is given to you and it is difficult to get your brain away.

Clik here to view.

With Peju Alatise, in her Lagos home studio:

RA: When did you transition your practice from architecture to art?

PA: For a while, I was torn between my architecture practice, design work, painting, sculpting and telling stories. It was like cooking with all of the condiments at the same time. My paintings look like sculptures and my sculptures look like paintings and they all have this long story about them and sometimes I design pieces that come with usable furniture pieces. I lacked editing in my work because I wanted to show everything in it. I wanted it to be a mini-me.

RA: What are you working on now?

PA: I took March off from the studio to write my third book. I went to South Africa and thought I would continue (in Lagos) but there's no electricity and the heat is driving me mad. I will go anywhere there's electricity! There has been a total blackout here for three months. Once in a while there's electricity for 15-30 minutes.

The queue (for generator fuel) probably takes 4 hours, you get back home with a headache that radiates down to your shoulders and armpits. You want to type but you can't think straight. You don't get anything here without a fight.

Clik here to view.

RA: How was your residency in Essaouira?

PA: Funny enough, the way I feel about Nigeria is exactly how Moroccans talked about their government. They are hard on their government but they stay because Africa is this gem of a place.

Clik here to view.

With Chief Nike Davies Okundaye, in Lagos and via telephone:

RA: You lost your mom at age 6, fled an arranged marriage at 13, survived 16 years with an abusive polygamist husband, mastered and preserved adire (traditional indigo dying). Your work is in the Smithsonian Museum and you operate Nigeria's largest art gallery as well as craft workshops in Osogbo and Lagos that double as safe havens for women and girls. Does anything hold you back?

NDO: I was never afraid of anything except politics. I never used to vote.

Politics in Nigeria is a dirty game. People are short-minded, always jealous of what women do. They will say, "Look at that woman, go and burn her house.' And then all you have worked for is gone.

RA: What made you decide to vote in elections?

NDO: I went to South Africa seven years ago. It was (a conference) organized by Clinton's wife, "Vital Voices", so women all over the world will have a voice. If they cheat me, all the other women will fight (for me). After the conference, we went to Fashola, the governor of Lagos state, and told him to put women in the cabinet. Now there are women in key positions, and the same in Ashun state. This conference made me want to vote, I voted for the first time.

RA: I understand you begin work before dawn. Will you take a break for the holidays?

NDO: All my artists come to eat Christmas dinner with me in Lagos. And I am going to Igidi for New Year's. I will make candied yam -- it makes everyone happy. In the village, people like python and monkey and bush meat for holidays. Because of Ebola now they said no more bush meat, but some people still eat it. I won't have it -- we are so scared. I will cook catfish and 'cow with a feather'. That's what people call chicken!

Clik here to view.