Twenty-five years ago today, the first Day Without Art began as the US art world's national day of action and mourning in response to the AIDS crisis. To make the public aware that HIV-AIDS can touch everyone, and inspire positive action, some 800 U.S. art and HIV-AIDS groups participated in the first Day Without Art, shutting down museums, sending staff to volunteer at AIDS services, or sponsoring special exhibitions of work about AIDS. Since then, Day Without Art has grown into a collaborative project in which an estimated 8,000 national and international museums, galleries, art centers, AIDS service organizations, libraries, high schools and colleges take part.

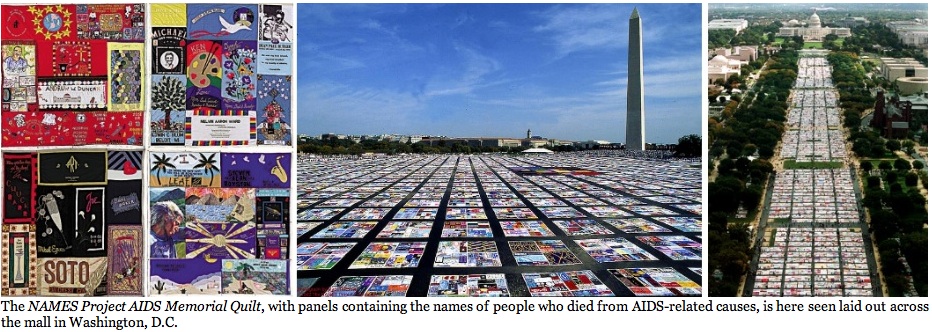

There were of course art and AIDS milestones to come before it. Most notable among them, in 1987, was the first public showing of the NAMES Project Memorial Quilt, often called the AIDS Memorial Quilt, occurs in 1987, two years after it was conceived and organized by AIDS activist Cleve Jones. The quilt was literally unrolled across the lawn of the National Mall in Washington, DC, whereby It rapidly became known as a memorial to, and celebration of, the lives of all the people who have died of AIDS-related causes. Weighing an estimated 54 tons, as of 2010, it is the largest piece of community folk art in the world. As social historian Gary Laderman notes, the NAMES Project Memorial Quilt filled a void in the lives of survivors at a time funeral homes and cemeteries refused to handle the AIDS-deceased's remains due to both the social stigma of AIDS and fear of its spread during a period before the disease came to be medically understood. During this period, the Quilt was often the only opportunity survivors had to remember and celebrate their loved ones' lives.

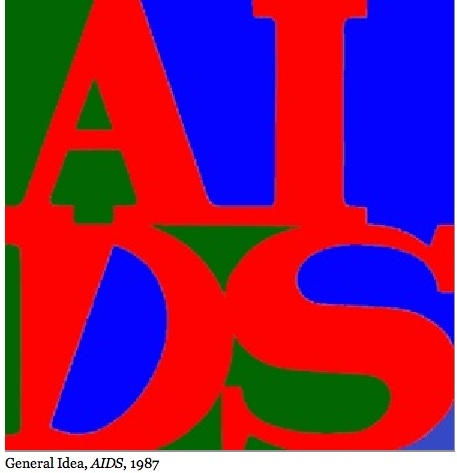

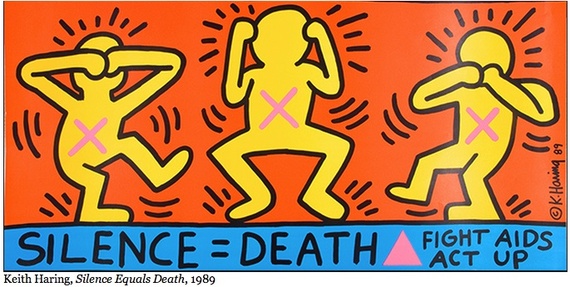

1987 is also the year that the veteran Canadian trio known as General Idea produce the AIDS era's premiere artistic icon. AIDS, a riff off Robert Indiana's 1960s LOVE icon (pictured with the above introduction to this feature), proves itself to be as existentially potent as it is visually bold and conceptually audacious in its appropriation of the 1960's logo of free love. It is fitting that Indiana's LOVE, which was so often interpreted as response to the Vietnam War, should factor into the General Idea's war against the invocation of AIDS as a weapon of sexual discrimination. The relevance of the logo, combined with the tragedy of AIDS being born in relationships of love, immediately ensures that it is taken up around the world as a banner for the campaign to end the contagion, just as the Gran Fury slogan Silence = Death internationally implicates the truly reprehensible, if not potentially criminal, behavior keeping the contagion alive.

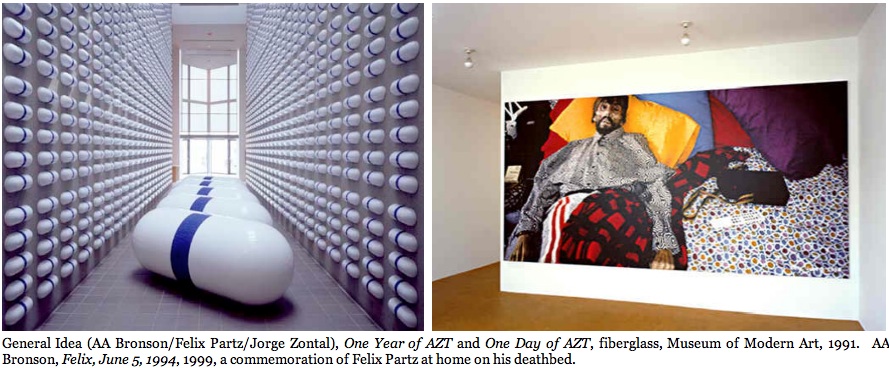

General Idea, whose queer art has been internationally exhibited since the early 1970s, would become decimated by the AIDS crisis, with two of its members, Jorge Zontel and Felix Partz, dying only months apart from each other in 1995. Surving member, A.A. Bronson, has since gone on to make an art of post-science shamanism geared for a generation seeking a healing that science has so far shown itself incapable of supplying. (See more on General Idea below.)

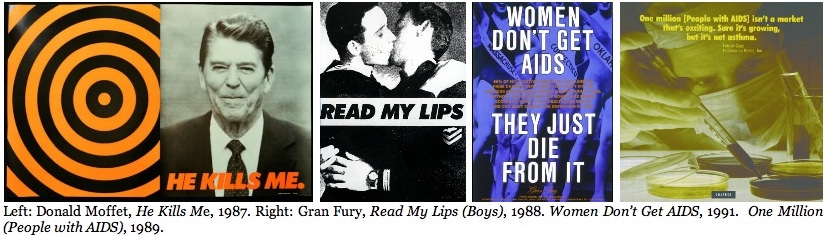

1987 is also the year that concerned LGBT individuals in New York City, outraged over the government's mismanagement of the AIDS crisis, concerned LGBT individuals in New York City unite to form the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT-UP. Centering their premiering demonstration on Wall Street to protest the profiteering of pharmaceutical companies in the production of AZT, seventeen members are arrested. With more protests planned, the coalition grows rapidly, and the accumulating voices grow into a roar that officials learned they couldn't ignore. When New Museum senior curator Bill Olander invited ACT-UP to stage a political action in the New Museum's Broadway window, he didn't know that he had less than nineteen months to live. He DID have a sense that he had put into motion a catalyst for radical change, even though he only saw its wheels turning in test runs.

By 1988, the activist vehicle that broke from that window into the streets came to be known as Gran Fury, after the brand of cars that make up the NYPD cruise and emergency fleet. Comprised of a loose-knit band of ACT-UP visualists--Donald Moffet, Marlene McCarty, Tom Kalin, Mark Simpson, John Lindell, Loring McAlpin and Avram Finklestein -- the team became affectionately known as the propaganda arm of ACT-UP. Finklestein had also earlier organized the Silence=Death Project, which created the iconically scathingly yet enduring and world-renown indictment and admonishment, Silence = Death (pictured with the above introduction to this feature). In real cognitive terms, Fury's propaganda was something called facts, something that the Reagan and Bush administrations eschewed for real propaganda, a.k.a. misinformation. Facts that the media wished under the carpet, Gran Fury retrieved to visibly and textually solidify in the collective consciousness.

Fury's visualizations employed in-your-face tactics every bit as aggressive and effective as any one of The United Colors of Benetton's shock campaigns of the same era. And for at least six years the collective showed all the direct marketing acumen of Madison Avenue's David Ogilvy combined with the art-savvy vision of Golden Square's Charles Saatchi thrown in. In just a short sampling of their combined aesthetic-pragmatic power, Fury left no corner of homophobia left unturned, pulling up and dispensing with the entire carpet of anti-queer bigotry, along with the hidden racisms, sexisms, and gender prejudice of the time along with it. The achieved effect was a cultivation of collective AIDS awareness that heightened the responsiveness levels of HIV positives and their families and friends, medical professionals, government officials and charitable donors. The difference between awareness and activism in the 1980s and the 1990s appear as if night were changed into day, and largely because the ACT-UP demonstrations and the Gran Fury/Silence=Death Project ad campaigns were ubiquitous, at least on the two American coasts.

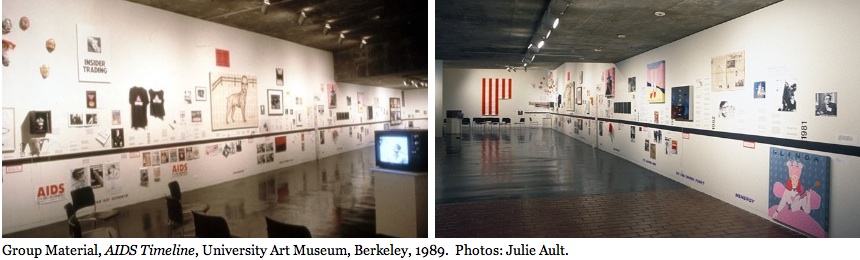

1989 is also the year that Group Material was formed, an artists collective comprised of many artists and art administrators, the most well known including Tim Rollins, Julie Ault, Doug Ashford and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. After completing a series of year-long presentations centered on the theme of Democracy at The Dia Foundation for Art in New York, Group Material went to Berlin, where they presented AIDS & Democracy at the Neue Gesellschaft fur Bildende Kunst. That same year they installed the project for which they remain most widely recognized, The AIDS Timeline, at the University Art Museum, Berkeley.

Group Material installations stood out for not being known for their visual aura as much as for their textual density. This aspect of compiling images, objects, and readings as if all coalesced into one text was most successful when employed in their timelines installed in galleries. It also served the collective well in achieving their mission, which they've stated to be the movement of "the idea of art from isolated models of refinement to a self-consciously political and cultural approach to communication. As the interface between subject matter and society, presentation space was adopted as a significant artistic medium, removing the distinction between artists and curators. Moreover, the status of presentation space itself as a standard of access to information was opened beyond the museum and gallery to engage the public through storefronts, talks, town meetings, newspaper ads, magazines, bus posters, etc."

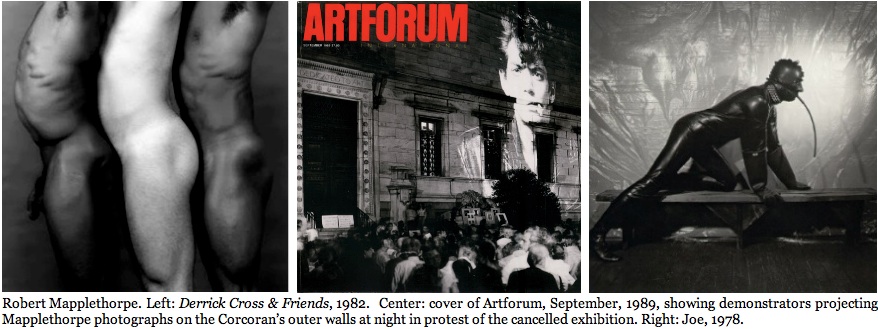

1989 is also the year that a traveling exhibition of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe scheduled to be hosted by the Corcoran Museum in Washington, DC was unceremoniously cancelled for obscenity by the museum's director, Christina Orr-Cahall, under pressure from the religious right. The public outcry made international news as protestors projected slides of Mapplethorpes's most explicit work on the sides of the museum's walls at night, which ARTFORUM emblazoned on its September cover.

The following April, police and deputies from the sheriff's office ordered the 400 visitors present to leave the opening of the Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective The Perfect Moment at the Contemporary Arts Museum in order to barricade the building and record the evidence on video for later us in the prosecution: the children's portraits of "Rosie" and Jesse McBride from the mid-seventies, on which exposed genitals were visible, plus five works from Mapplethorpe's legendary X Portfolio, which depicts homosexuals engaged in performing S/M practices. On September 28 1990, the so-called Mapplethorpe Obscenity Trial began in Cincinnati. If the district attorney, high police officials, local businessmen, and various anti-pornography groups were to have their way, Dennis Barrie, the director of the hosting museum, could have looked forward to a maximum sentence of six months for the dissemination of pornography. The trial ended with an acquittal on the defense that the photographs were "figurative studies" and "classical compositions," even though the jury was made up of men and women from the working class none of whom had previous contact with art or photography.

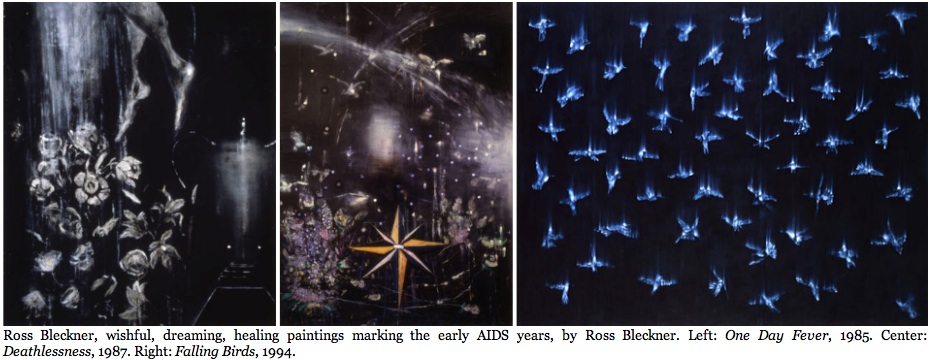

Not all AIDS-related exhibitions were impelled by fury or held politics as its main agenda. Ross Bleckner proved that political art neither has to directly and pointedly articulate its subjects and objectives, nor render them in a pictorial social realism. The time and place of his exhibitions spoke for themselves. Viewers even today can see the romanticized imagery stand as painted eulogies to lost friends, even as they evoked the collective loss of a generation of survivors asking the hows, whys and what ifs of the AIDS epidemic. Which is why walking into a Bleckner exhibition in the late 1980s, though by no means a pious affair, compelled the visitor to silence and personal commemoration on no other cue but the paintings before us.

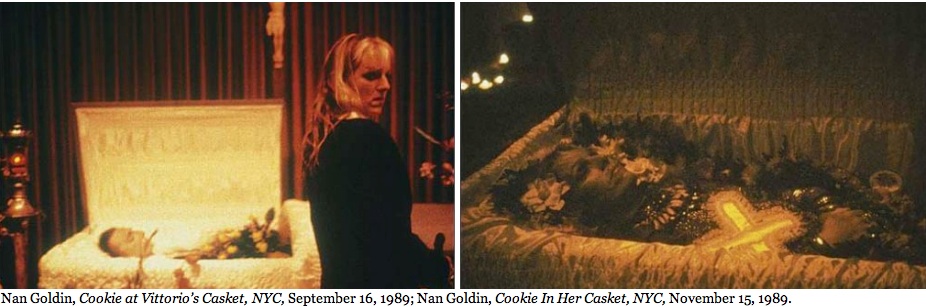

From its introduction in the art world, Nan Goldin's art became something of a chronicler of the New York underground. She filled a void that opened in art photography with the death of Diane Arbus, except that Arbus was something of a tourist in the world of the recalcitrant nonconformist, the self-stylized freak and the misfit. Goldin lived the life she photographed. Her "subjects," which strike some audiences as eccentric, self-possessed, willfully retreating into the wounds of cultural injury, are to Goldin beloved lovers and friends. In this respect Goldin was made political at least at the outset only because the friends in her life unknowingly thrust the power of art into her hands, through her camera, into her brain, where the force of it all must have been anything but chosen.

It was through her friends that Goldin became a most unwilling chronicler of the early spread of AIDS. As Goldin wrote in "20 Years: Aids & Photography" for The Digital Journalist, "AIDS changed everything in my life. There's life before AIDS, and after AIDS... We were in Fire Island that first time we'd heard about AIDS, in July of 1981. I was with Cookie Mueller, Cookie's lover, Sharon, and photographer David Armstrong, one of my oldest, best friends, and 2 or 3 other boys. Cookie used to write a monthly art critique for Details Magazine. She was the starlet of the Lower East Side: a poetess, a short-story writer, she starred in John Waters's early movies. She was sort of the queen of the whole downtown social scene."

Of the many she photographed in their last stretch of life, Cookie Mueller was the most famous. A writer with a tres hip cult following, she became a muse to Goldin, in that she crafted a portal of words onto the wild world that was New York, in her case in the 1970s. "I didn't think of them as people with AIDS," Goldin writes. "About '85, I realized that many of the people around me were positive... At that stage, we still didn't know very much. There was a lot of ignorance. We were very obsessed with what caused it: There were all kinds of rumors, everything from amyl nitrate to bacon. People were tested and being told they had something called ARC, that quickly became medically non-relevant. I was in denial that people were going to die. I thought people could beat it. And then people started dying."

Here Goldin photographed the wakes of Mueller's husband, Vittorio, whom she married only a few months before, and then the wake of Mueller, again within the space of mere weeks.

Neo-Pop and Graffiti Art icon, Keith Haring, was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988. His website states that in 1989, he established the Keith Haring Foundation to provide funding and imagery to AIDS organizations and children's programs, and to expand the audience for Haring's work through exhibitions, publications and the licensing of his images. Haring enlisted his imagery during the last years of his life to speak about his own illness and generate activism and awareness about AIDS. Haring died of AIDS related complications at the age of 31 on February 16, 1990. A memorial service was held on May 4, 1990 at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City, with over 1,000 people in attendance.

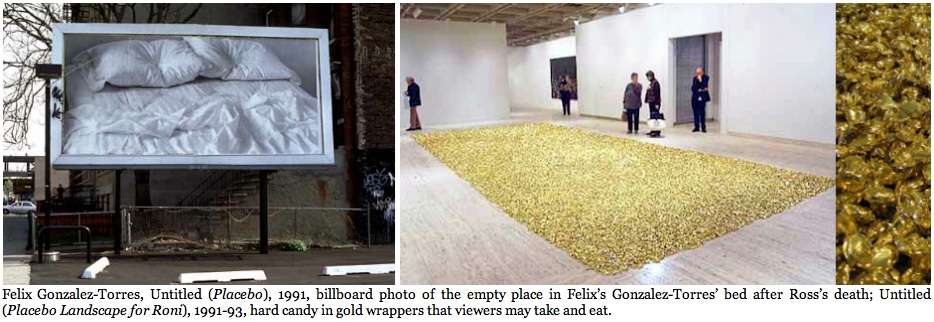

1991-1993: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the conceptual sculptor who in January 1996 died of AIDS at age 38, combined his personal experiences with public conceptual art installations. In one exhibit, he piled wrapped candy in a corner and invited viewers to take one, replenished from an "endless supply," an idyllic sentiment exemplary of a desire for heaven on earth. Yet his art is anything but sentimental. His billboard installations of the early 1990s displaying the photographic images of his empty bed are simple facts of loss as much as they are tributes to his lover lost to AIDS in a public gesture that directs his grief into the collective that receives all private life events as political motivations and ends. In some of Gonzalez-Torres' minimalist candy installations the weight of the candy is to equal his lover's weight, other's his own weight, and still others the weight of both men combined. In the above installation, the candy is to be maintained at 1200 pounds.

1991-1995: General Idea, the trio of artists whose queer art has been internationally exhibited since the early 1970s, would become decimated by the HIV virus, with two of its members, Jorge Zontel and Felix Partz, dying only months apart from each other in 1995. Surviving member, AA Bronson, has since gone on to make an art of post-science shamanism geared for a generation seeking a healing that science has so far shown itself incapable of supplying. (See more about General Idea and their iconic AIDS art in Part 4, When the Personal Is Made Political: Left Political Art Timeline, 1980-1989.)

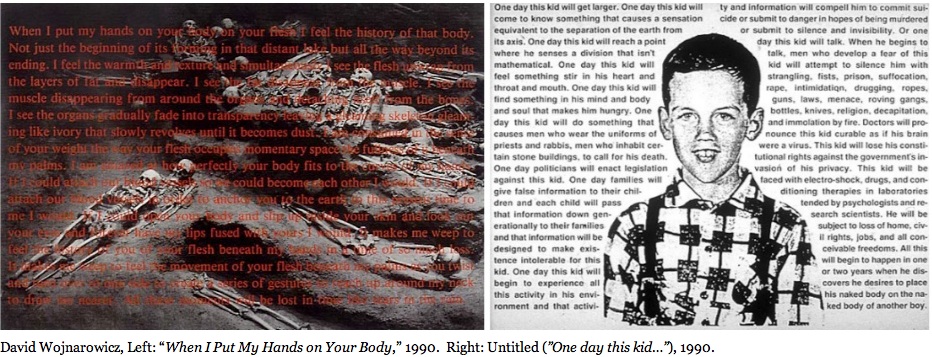

1992: Artist and writer David Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related causes. Although feminists in the 1970s had widely disseminated the notion of the person being political, as late as the mid 1980s, few male artists, gay or straight, made his personal life the center of his work as acutely and ultimately as tragically as had David Wojnarowicz. Then, too, it appears that Wojnarowicz's work from the very beginning emerged directly from his personal experience. He claimed that he didn't study art history, didn't go to college, and he was begrudged for not being an art world networker. And so he made his art about the things he knew: his boyhood; his sexuality; life on the street; and witnessing his body as it progressively fell victim to the HIV virus. A prolific and impassioned writer, the text of his art work, When I Put My Hands On Your Body, overlain the image of excavated graves, speaks as freshly these years after his death as when he wrote them.

"When I put my hands on your body on your flesh I feel the history of that body. Not just the beginning of its forming in that distant lake but all the way beyond its ending. I feel the warmth and texture and simultaneously I see the flesh unwrap from the layers of fat and disappear. I see the fat disappear from the muscle. I see the muscle disappearing from around the organs and detaching itself from the bones. I see the organs gradually fade into transparency leaving a gloaming skeleton gleaming like ivory that slowly revolves until it becomes dust. I am consumed in the sense of your weight the way your flesh occupies momentary space the fullness of it beneath my palms. I am amazed at how perfectly your body fits to the curves of my hands. If I could attach our blood vessels so we could become each other I would. If I could attach our blood vessels in order to anchor you to the earth to this present time to me I would. If I could open up your body and slip inside your skin and look out your eyes and forever have my lips fused with yours I would. It makes me weep to feel the history of your flesh beneath my hands in a time of so much loss. It makes me weep to feel the movement of your flesh beneath my palms as you twist and turn over to one side to create a series of gestures to reach up around my neck to draw me nearer. All these memories will be lost in time like tears in the rain."

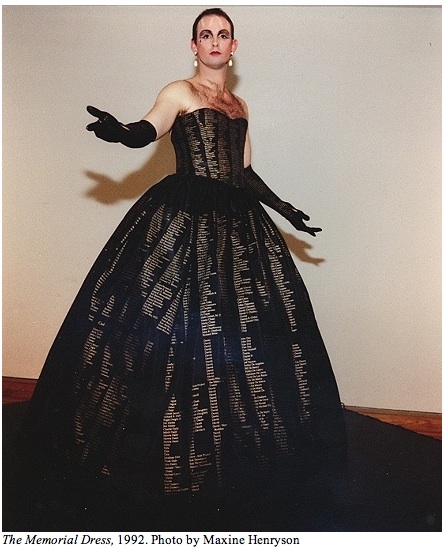

In 1994 Ann Pasternak had only just begun her long tenure as the Director of Creative Time in New York the year that she bravely co-sponsored Hunter Reynolds: Patina Du Prey's Memorial Dress, a healing ritual and performance sculpture. I say brave, because in writing the affair sounds potentially offensive, introducing the signage of a drag queen--which to many viewers brings with it the image of outrageous disregard for convention--at a function demanding propriety out of respect for the dead and their grieving survivors. In fact, Reynolds ensures that there is not only no glimmer of camp, irony, or humor breaking through the spectacle of a large balding man wearing a classically handsome black bell dress while rotating on a dais for the audience's riveted inspection. It's the stillness and the silence of the gallery's numerous and lingering visitors that encourages our silence, then directs our eyes onto the names of the then 25,000 AIDS dead printed exquisitely in gold and undulating in and around the dress's sumptuous folds. The atmosphere not only cultivates respect, but signals that, regardless of the dress, this is no ordinary drag queen taken to the stage. Reynolds is in fact invoking the history of the healing shaman ritual in which the tribal shaman, usually a man, dons the traditional clothing of the tribe's women to summon a power ascribed in the society to women alone, yet which becomes more concentrated when the conduit of the power passed to him is male. Perhaps because it is an acknowledgement too esoteric to be understood in the modern context it is presented, Reynolds has seen to it that the bodice of the strapless dress is cut for a male torso. It takes some time to notice the difference, but it no less discretely registers on our mind's eye until it dawns on us that, besides the absence of a wig, the artist declines to simulate cleavage. The overall effect is provocative not so much for the negation of stereotypes, but for the many enigmas bestowing an aura of mystery and awe onto this angel of deathly benevolence.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on Facebook and Twitter.