The Blind Prophet.

Let me conclude this sequence of posts with a slightly more detailed examination of what it means to an artist -- in this case me -- to be able to follow in real time the work of another artist -- in this case, sculptor Sabin Howard.

Howard lives and works somewhere in New York, but most of my fairly minimal interaction with him is over Facebook. Lately, he has been working on some remarkable drawings. Here is the first one he posted:

![2014-01-08-graphic13.jpg]()

Sabin Howard, Untitled Study, 2013, 18"x14", pencil on paper

Before we get down to analysis here, let me explain that I had an immediate and visceral reaction to this drawing. I thought, "Oh, I love this." Sometimes you fall in love with drawings; I fell in love with this.

Now that we've got the intensity of my reaction clear, I can attempt to dissect its cause. But I can make you no promises. The analysis is after-the-fact.

The first thing, which is evident to any artist with experience in figure drawing and which Howard confirms when asked, is that there was no model for this drawing. It is a construction: Howard constructed it based on his knowledge of anatomy, and the theory of the body he has derived from that knowledge. As he puts it:

![2014-01-08-graphic14.jpg]()

Sabin Howard, Untitled Study, 2013, 18"x14", pencil on paper

That kind of offhand remark can only occur in the context of a wide, deep knowledge of the body as a machine. This mode of knowing characterized a sect of artists over many centuries, from Michelangelo to John Tenniel. It is pursued internally out of a thirst for absolute understanding, for a sense of the body that does not leave any part about right, but rather utterly right, exact as to itself. This pursuit replaces the real bodies of real people with a set of forms derived in the mind: the body as parsed and created in the mind, cleaned of its inconsistencies and variations, made perfect and harshly true. It is only in this mode of art-making that the artist becomes really god-like, in the sense of creating a world. The artist becomes a calipers-god, working from first principles all the way up to something with a complexity like life, but a life owing nothing to nature, and everything to mindfulness.

Such a pursuit etches its nature into the aesthetics of its creations. There is a sense of glaring reason to the work, a pitiless, shadowless brilliance. In The Secret History, Donna Tartt does some writing which has stuck with me on the Greek mindset. Discussing words for "fire," her narrator says:

And elsewhere:

"Beauty is terror. Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it."

Yes, that is it. The form of beauty Howard pursues is the Greek beauty, awful, unmerciful, scouring. There is no more hiding from the crushing demands of virtue or from the stark final nature of things in his conception of the figure. Howard is, after a manner of speaking, a servant of Apollo, and not just any servant. He is trying to become Tiresias; he scarcely requires eyes to see what he sees.

![2014-01-08-graphic15.jpg]()

Sabin Howard, Untitled Study, 2013, 18"x14", pencil on paper

This is not the only thing we need, but if we do not have this, we might as well have nothing.

Now, this is not how I myself ordinarily draw. My fundamental means of drawing is not knowledge but sight, specifically sight of shapes. I've written about my native mode of visual cognition here. For all that, the mind has difficulty integrating pure shape into unified human forms. So I got around the problem by taking gross anatomy -- I hacked up cadavers for a couple years, and drew my own anatomical atlas.

![2014-01-08-graphic16.jpg]()

Daniel Maidman, Front and Back Views of the Spine, 2002, 14"x11", pen on paper

This emphasis on explicit knowledge of anatomy allowed me to introduce a convincing internal structure into my figures, but I never sought to foreground the practice. For Howard, the body in itself, as a noble machine interfacing with a world of forces, is a topic of obsession. For me, the body was always a secondary concern, beautiful but mainly as the repository of the invisible person. It's the sheet the ghost wears so you can see it.

My approach is not better than his; his approach is not better than mine. There is room enough in the world for both of us, and I think there is need enough in the soul for both of us too.

Be that as it may, when you look at art that moves you profoundly, it rubs off on you a bit. So the next time I had a long pose to draw, this was what I drew:

![2014-01-08-graphic17.jpg]()

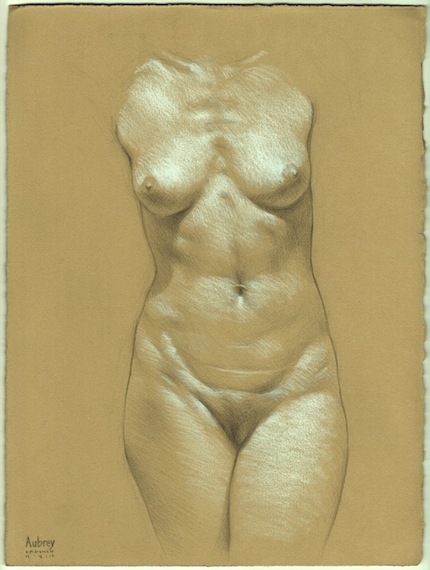

Daniel Maidman, Aubrey's Torso, 2013, 15"x11", pencil on paper

It's not really a Howard drawing, but it owes something to Howard. It is a more complete section of the body, more unified in its conception, than I usually bother with. I emphasized putting every part in, and getting every part right. And I did have to do a good deal of construction -- as people who have drawn Aubrey know, she has hair down to her waist. During this pose, her hair was in front of her, on her left, blocking a hefty swath of my view. So I had to make up a lot of the right side of the drawing, based on glimpses, symmetry and general knowledge.

After that, the effect of looking at Howard's work persisted, right through an event important to me for other reasons. What happened was, I had a chance to work with Piera again.

The Hope of Eternal Return

Over time, I think we tend to notice that life involves a lot of loss. You choose some way to live, you live that way for a while, and then you lose whatever it was. This is a constantly renewed process, and whatever the rewards of new things, the pain of loss persists. Rarely does life permit return.

I have had five primary muses in my life as an artist, and Piera is the fourth. My wife and I became close friends with her and her husband Emanuele, also an artist. Making people feel loved is a talent, or maybe a state of character. Whatever it is, I know of nobody in whom it is more inborn than Piera. My first painting of her was also my first painting as a technically well-developed painter:

![2014-01-08-graphic18.jpg]()

Daniel Maidman, Piera, 2008, 28"x22", oil on canvas

But Piera has no time for modeling anymore; she and Emanuele had a baby a few years ago, and he is the focus of their lives. Over Christmas, though, owing to a combination of vacation overlaps, Piera had a few hours to come model for me. I elected to do preparatory sketches for paintings.

Well, it turns out that Piera actually looks a bit Howardish herself these days. When I first met her in 2007, she was strong but curvy. Almost seven years later, she still has the curvy skeletal architecture, but she's worked off a lot of the flesh that used to overlie it. She's wiry now, the kind of wiry that will be formally beautiful all the way to 70 or 80 years, like Saint Jerome. The first drawing I did of her reflected this combination of her revised anatomy and my exposure to Howard's work:

![2014-01-08-graphic19.jpg]()

Daniel Maidman, Preparatory Sketch for a Painting of Piera I, 2013, 15"x11", pencil on paper

I like this very much; I liked that, like cigarette carcinogens, superpowers can be absorbed second-hand. It is good to draw the complete human machine sometimes, in its naked excellence. However, in my second drawing, my natural tendencies reasserted themselves.

![2014-01-08-graphic20.jpg]()

Daniel Maidman, Preparatory Sketch for a Painting of Piera II, 2013, 15"x11", pencil on paper

Here I followed shape at the expense of proportion. There are no lines of perspective, there is no telling if I got it right or wrong. There may well be no right or wrong to this. It is as irregular as French in comparison with the martial Greek of the first one. It doesn't even especially look like Piera. And yet to me, it very much feels like her. It feels like her personality and mood; it is the Piera we both recognized when we considered it after the sitting. This is the landscape of my native sense of beauty.

Drawing Piera again, I felt a happiness unique to the restoration of some way of living we had loved, and lost. People, places, practices, things -- all of them are ways of living, and we do not own any of them. I had the good fortune to live my life as an artist in the company of Piera for some years. Later, I lost her. I moved on, and I was happy, but time itself is an affront to my sensibilities, and I never stopped grieving for this absent part of my life. Then she came back to work with me again, and I felt right with myself and the world. This was the happiness of restoration.

There is no moral to this winding anecdote. Sabin Howard, in my opinion, has made a breakthrough in these drawings in his passionate pursuit of a particular fundamental form of beauty. If I were not me, as an artist, I might well want to be him. I have a different form of beauty which is natural to me. I am seeking to become excellent in mine as he is in his. I become richer seeing what he does, and I hope you become richer considering this account.

Next

This is what my life is like as an artist, making art and writing about art, among artists. Many of the best I know are kind. I often write about friends, but I do not write well of them because they are friends. Rather, I sought to become friends with them because I first knew and admired their work.

Of course I want to be the best artist in the world. All artists must. But that's for later. For now, I do not even want to be the best artist in the room. I want to be an artist worth considering in a room with many splendid artists.

I worked hard as hell to get good enough even to gain entry to that room, and I think I have gotten through the door. I remain in New York so that this concept of a room will find embodiment, sometimes, in actual rooms, where I will actually run into people like Steven Assael and Dorian Vallejo, Claudia Hajian and Fred Hatt, Michelle Doll and Lisa Lebofsky and Bonnie DeWitt, Jean-Pierre Roy and Noah Becker, and Sabin Howard -- and many more besides.

This is the best picture I can draw for you of my part of the art scene in New York at the end of 2013 and the start of 2014. In the next year, I hope to go on working hard, receiving inspiration sometimes, seeing work, talking with artists, self-promoting as I can -- and trying not to turn into a dick.

My wish for you is that you will have something worthy of passion in your life; that you will have scope to work on becoming excellent at it; and that you will not be alone in your passion, but will be welcomed in the company of others who share in it. If you've already got those things, I hope you won't forget that they represent a wealth beyond measure.

As usual, I am seeking to instruct myself first, but if I'm saying anything useful for you, I'm glad for that as well.

Let me conclude this sequence of posts with a slightly more detailed examination of what it means to an artist -- in this case me -- to be able to follow in real time the work of another artist -- in this case, sculptor Sabin Howard.

Howard lives and works somewhere in New York, but most of my fairly minimal interaction with him is over Facebook. Lately, he has been working on some remarkable drawings. Here is the first one he posted:

Sabin Howard, Untitled Study, 2013, 18"x14", pencil on paper

Before we get down to analysis here, let me explain that I had an immediate and visceral reaction to this drawing. I thought, "Oh, I love this." Sometimes you fall in love with drawings; I fell in love with this.

Now that we've got the intensity of my reaction clear, I can attempt to dissect its cause. But I can make you no promises. The analysis is after-the-fact.

The first thing, which is evident to any artist with experience in figure drawing and which Howard confirms when asked, is that there was no model for this drawing. It is a construction: Howard constructed it based on his knowledge of anatomy, and the theory of the body he has derived from that knowledge. As he puts it:

I wanted to do more experimentation with the conceptualization of the body in geometric terms, how all the parts fit together. There is a lot about the architecture of the figure being the skeleton. And the musculature being the spinning organic element. As a sculptor I am an architect working with organic form.

Sabin Howard, Untitled Study, 2013, 18"x14", pencil on paper

That kind of offhand remark can only occur in the context of a wide, deep knowledge of the body as a machine. This mode of knowing characterized a sect of artists over many centuries, from Michelangelo to John Tenniel. It is pursued internally out of a thirst for absolute understanding, for a sense of the body that does not leave any part about right, but rather utterly right, exact as to itself. This pursuit replaces the real bodies of real people with a set of forms derived in the mind: the body as parsed and created in the mind, cleaned of its inconsistencies and variations, made perfect and harshly true. It is only in this mode of art-making that the artist becomes really god-like, in the sense of creating a world. The artist becomes a calipers-god, working from first principles all the way up to something with a complexity like life, but a life owing nothing to nature, and everything to mindfulness.

Such a pursuit etches its nature into the aesthetics of its creations. There is a sense of glaring reason to the work, a pitiless, shadowless brilliance. In The Secret History, Donna Tartt does some writing which has stuck with me on the Greek mindset. Discussing words for "fire," her narrator says:

I can only say that an incendium is in its nature entirely different from the feu with which a Frenchman lights his cigarette, and both are very different from the stark, inhuman pur that the Greeks knew, the pur that roared from the towers of Ilion or leapt and screamed on that desolate, windy beach, from the funeral pyre of Patroklos.

And elsewhere:

"Beauty is terror. Whatever we call beautiful, we quiver before it."

Yes, that is it. The form of beauty Howard pursues is the Greek beauty, awful, unmerciful, scouring. There is no more hiding from the crushing demands of virtue or from the stark final nature of things in his conception of the figure. Howard is, after a manner of speaking, a servant of Apollo, and not just any servant. He is trying to become Tiresias; he scarcely requires eyes to see what he sees.

Sabin Howard, Untitled Study, 2013, 18"x14", pencil on paper

This is not the only thing we need, but if we do not have this, we might as well have nothing.

Now, this is not how I myself ordinarily draw. My fundamental means of drawing is not knowledge but sight, specifically sight of shapes. I've written about my native mode of visual cognition here. For all that, the mind has difficulty integrating pure shape into unified human forms. So I got around the problem by taking gross anatomy -- I hacked up cadavers for a couple years, and drew my own anatomical atlas.

Daniel Maidman, Front and Back Views of the Spine, 2002, 14"x11", pen on paper

This emphasis on explicit knowledge of anatomy allowed me to introduce a convincing internal structure into my figures, but I never sought to foreground the practice. For Howard, the body in itself, as a noble machine interfacing with a world of forces, is a topic of obsession. For me, the body was always a secondary concern, beautiful but mainly as the repository of the invisible person. It's the sheet the ghost wears so you can see it.

My approach is not better than his; his approach is not better than mine. There is room enough in the world for both of us, and I think there is need enough in the soul for both of us too.

Be that as it may, when you look at art that moves you profoundly, it rubs off on you a bit. So the next time I had a long pose to draw, this was what I drew:

Daniel Maidman, Aubrey's Torso, 2013, 15"x11", pencil on paper

It's not really a Howard drawing, but it owes something to Howard. It is a more complete section of the body, more unified in its conception, than I usually bother with. I emphasized putting every part in, and getting every part right. And I did have to do a good deal of construction -- as people who have drawn Aubrey know, she has hair down to her waist. During this pose, her hair was in front of her, on her left, blocking a hefty swath of my view. So I had to make up a lot of the right side of the drawing, based on glimpses, symmetry and general knowledge.

After that, the effect of looking at Howard's work persisted, right through an event important to me for other reasons. What happened was, I had a chance to work with Piera again.

The Hope of Eternal Return

Over time, I think we tend to notice that life involves a lot of loss. You choose some way to live, you live that way for a while, and then you lose whatever it was. This is a constantly renewed process, and whatever the rewards of new things, the pain of loss persists. Rarely does life permit return.

I have had five primary muses in my life as an artist, and Piera is the fourth. My wife and I became close friends with her and her husband Emanuele, also an artist. Making people feel loved is a talent, or maybe a state of character. Whatever it is, I know of nobody in whom it is more inborn than Piera. My first painting of her was also my first painting as a technically well-developed painter:

Daniel Maidman, Piera, 2008, 28"x22", oil on canvas

But Piera has no time for modeling anymore; she and Emanuele had a baby a few years ago, and he is the focus of their lives. Over Christmas, though, owing to a combination of vacation overlaps, Piera had a few hours to come model for me. I elected to do preparatory sketches for paintings.

Well, it turns out that Piera actually looks a bit Howardish herself these days. When I first met her in 2007, she was strong but curvy. Almost seven years later, she still has the curvy skeletal architecture, but she's worked off a lot of the flesh that used to overlie it. She's wiry now, the kind of wiry that will be formally beautiful all the way to 70 or 80 years, like Saint Jerome. The first drawing I did of her reflected this combination of her revised anatomy and my exposure to Howard's work:

Daniel Maidman, Preparatory Sketch for a Painting of Piera I, 2013, 15"x11", pencil on paper

I like this very much; I liked that, like cigarette carcinogens, superpowers can be absorbed second-hand. It is good to draw the complete human machine sometimes, in its naked excellence. However, in my second drawing, my natural tendencies reasserted themselves.

Daniel Maidman, Preparatory Sketch for a Painting of Piera II, 2013, 15"x11", pencil on paper

Here I followed shape at the expense of proportion. There are no lines of perspective, there is no telling if I got it right or wrong. There may well be no right or wrong to this. It is as irregular as French in comparison with the martial Greek of the first one. It doesn't even especially look like Piera. And yet to me, it very much feels like her. It feels like her personality and mood; it is the Piera we both recognized when we considered it after the sitting. This is the landscape of my native sense of beauty.

Drawing Piera again, I felt a happiness unique to the restoration of some way of living we had loved, and lost. People, places, practices, things -- all of them are ways of living, and we do not own any of them. I had the good fortune to live my life as an artist in the company of Piera for some years. Later, I lost her. I moved on, and I was happy, but time itself is an affront to my sensibilities, and I never stopped grieving for this absent part of my life. Then she came back to work with me again, and I felt right with myself and the world. This was the happiness of restoration.

There is no moral to this winding anecdote. Sabin Howard, in my opinion, has made a breakthrough in these drawings in his passionate pursuit of a particular fundamental form of beauty. If I were not me, as an artist, I might well want to be him. I have a different form of beauty which is natural to me. I am seeking to become excellent in mine as he is in his. I become richer seeing what he does, and I hope you become richer considering this account.

Next

This is what my life is like as an artist, making art and writing about art, among artists. Many of the best I know are kind. I often write about friends, but I do not write well of them because they are friends. Rather, I sought to become friends with them because I first knew and admired their work.

Of course I want to be the best artist in the world. All artists must. But that's for later. For now, I do not even want to be the best artist in the room. I want to be an artist worth considering in a room with many splendid artists.

I worked hard as hell to get good enough even to gain entry to that room, and I think I have gotten through the door. I remain in New York so that this concept of a room will find embodiment, sometimes, in actual rooms, where I will actually run into people like Steven Assael and Dorian Vallejo, Claudia Hajian and Fred Hatt, Michelle Doll and Lisa Lebofsky and Bonnie DeWitt, Jean-Pierre Roy and Noah Becker, and Sabin Howard -- and many more besides.

This is the best picture I can draw for you of my part of the art scene in New York at the end of 2013 and the start of 2014. In the next year, I hope to go on working hard, receiving inspiration sometimes, seeing work, talking with artists, self-promoting as I can -- and trying not to turn into a dick.

My wish for you is that you will have something worthy of passion in your life; that you will have scope to work on becoming excellent at it; and that you will not be alone in your passion, but will be welcomed in the company of others who share in it. If you've already got those things, I hope you won't forget that they represent a wealth beyond measure.

As usual, I am seeking to instruct myself first, but if I'm saying anything useful for you, I'm glad for that as well.