Dear Harold,

When searching for family roots in the South, a researcher might assume his or her African American ancestors were slaves. While it is true that, by far, the overwhelming percentage of black people in the South were doomed to spend their entire lives in slavery prior to the Civil War, it is also true that a small percentage lived as free citizens. And some, like your ancestor, were even able to prosper.

In 1840, for example, five years before your ancestor died, there were a total of 319,599 free black people living in the United States, about 13.4 percent of the entire black population, as Ira Berlin writes in Slaves Without Masters. Of those, 170,728 lived in the North and 215,575 lived in the South. North Carolina was fourth in the South behind Maryland, Virginia, and Louisiana with a total of 22,732 free blacks, or about 8.5% of the state's total black population. This makes sense, since the vast majority of free black people lived in the Upper South (174,357 in 1840 versus 41,218 in the Lower South in 1840).

Lewis Freeman was one of those free black citizens of North Carolina in 1840, which makes it more likely we'll find an answer to your search to find his birthdate. Unfortunately, however, few records from Chatham County or the Pittsboro area from the early 1800s exist. In North Carolina, births and deaths were not recorded until after 1913, and marriages were often lost or not recorded regularly before 1868. So, as is the case for many who lived in the 1700s and early 1800s, no clues exist about Lewis Freeman's age in vital records. Accordingly, to find the answer to your question, we had to search elsewhere.

Putting Down Roots in Pittsboro

Remarkably, your ancestor was a very successful early black settler in Pittsboro, North Carolina. Lewis was able to purchase at least 16 lots in town and 20 acres in surrounding Chatham County. We get a sense of his holdings from the will he wrote in January 1845 (and recorded in August of that same year). To his wife, Creecy, Lewis left their home and various lots in Pittsboro as well as 20 acres in surrounding Chatham County. His original house, located on Main Street in Pittsboro, was a typical one-room structure. Very few African Americans are able to identify the home their ancestor occupied before the Civil War, but you are among the fortunate ones! Although Lewis's home has been modified over the years, enough of it has remained to earn a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in North Carolina.

Clearly, your ancestor accumulated an impressive real estate portfolio. Less clear is the source of Lewis's wealth. The early census records list him as being employed in agriculture, but he may very well have been more than a farmer.

In addition, and we are sure that this will come as a surprise to you and your family: your ancestor, Lewis Freeman, a free black man, was himself a slave owner!

Family of Lewis Freeman

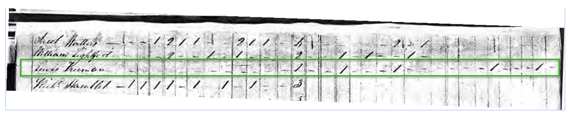

Amazingly, according to the 1820 census, which we found on Ancestry.com, Lewis had two slaves living in his household: a male and a female, both under the age of 14.

A detail from the 1820 U.S. Federal Census for Lewis Freeman and household at Ancestry.com.

Why, you might reasonably ask, would a free black man own slaves? We can't know for sure in Lewis's case, but they may have been family members that he bought in order to keep them in his family, and protect them from being owned by white masters. It wasn't unheard of for black family members to be bought and kept as slaves by other family members in these years, since in many Southern states, freed slaves had to leave the state or face being arrested and sold back into slavery. In other words, it was a desperate, but clever, way to keep the family together.

While Freeman's will refers only to his wife Creecy and does not mention any children or slaves, documentation for the National Register of Historic Places does mention a son named Waller. And Waller's probate records from 1868 shed light on the matter:

That one Lewis Freeman a free man of color the father of the said Waller and Grandfather of the plaintiffs....purchased from one C J Williams of Chatham County, N.C. on the 11th day of May 1814 Maria the Mother of the said Waller and with who the said Lewis lived as man and wife up to the death of the said Maria; this purchase was after the birth of the said Waller and the said [bill] of Sale from the said Williams to the said Lewis is registered in the office of the Register of Chatham County....the said Waller was purchased by the late George E Badger and the said Geo[rge] E Badger afterwards to wit on the 6th day of October 1830 sold the said slave to his father the said Lewis.

What this means is Lewis purchased a woman named Maria, his first wife, from one man. Maria was his son's mother. And then, after their son, Waller, was born, he purchased Waller from another man. That way, Lewis, a free black man, was able to live with his slave wife and child as a family. Seven years later, after Maria had died, Lewis made a remarkable decision: he decided to sell their surviving son to a man named R. Tucker, who took Waller to New York City in order to free him. We actually found the deed of manumission executed on October 4, 1837! So you descend from two generations of free people of color! It couldn't have been an easy decision, but it ensured that Lewis Freeman's son would be a free man. Remaining in the South, Lewis married a woman named Creecy, who eventually inherited his estate.

Estimating Lewis Freeman's Birth Year

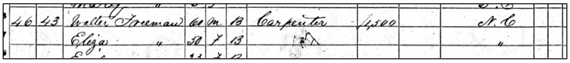

We believe that we have found the approximate answer to your question in the last federal census taken before the outbreak of the Civil War. As shown in an excerpt from the 1860 census below, Waller Freeman, Lewis's freed son, was recorded as 60 years old, meaning he was born around 1800.

A detail from the 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Waller Freeman and household at Ancestry.com.

If Waller was born in 1800, and his father was at least 18 years old when Waller was born, then Lewis was born no later than 1782, which was a year before the American Revolution ended.

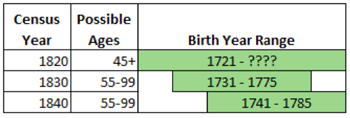

We can only give you an estimate of your ancestor's age, because before 1850, exact ages were not given in the U.S. Federal Census. Only age ranges were noted. In the 1800 and 1810 U.S Federal Censuses in Chatham, Lewis Freeman was counted, meaning that he was free at least by the beginning of the nineteenth-century. But, like other free people of color and slaves, no other data was listed in those two records. But the census records from 1820, 1830, and 1840, however, give us more information, thankfully. In those, Lewis was listed as head of household and, assuming he was the oldest male listed, we can make the following guesses about his birth year:

Using the largest lower bound and the smallest upper bound (above), allows us to narrow the possible years of Lewis' birth to between the years 1741 and 1775, which means he would have been between 70 and 104 when he died in 1845. Like many people who lived in the early 1800s and before, we may never know the exact year of Lewis Freeman's birth.

Not every question we have about our ancestors can be answered; and sometimes when records exist, we still can't answer every question exactly. But by digging for clues and analyzing them within the context of their times, we can begin to get a sense of the kind of person they were and how they lived their lives. In your case, we can begin to see how very complicated the life of a free person of color could be, and the extremely difficult choices that they had to make to protect the people they most loved. Your desire to find Lewis Freeman's birth date enabled us to make three astonishing discoveries about your fascinating ancestor: first, we were able to uncover the extent of his considerable estate, indicating that he was certainly one of the most prosperous free people of color in his lifetime; second, we were able to unveil the complicated family structure he had to create as a "slaveowner" in order to live with his first wife Maria and their son Waller; and third, and most poignantly, we were able to discover the ingenious way that he invented to free his enslaved son. When death set his wife free from this earth, Lewis took pains to see that their son was set free from slavery in the South, by selling him to a friend who would free him in the North. Since it is highly unlikely that Waller would risk returning to a slave state and being illegally re-enslaved, it is highly likely that Lewis knew, by taking this decision, he would never see his son again. It would take a bloody civil war nearly 30 years later to relieve other black fathers in the South of that terrible burden.

Do you have a mystery in your own family tree? Or have you wondered what family history discoveries you could make with a DNA test? Send Henry Louis Gates, Jr and his team of Ancestry experts your question at ask@ancestry.com.