As the world become increasingly surrealistic, it is fitting that a major exhibition on André Breton, the father of surrealism, is being held in the Cahors Museum, in southwestern France until the end of December.

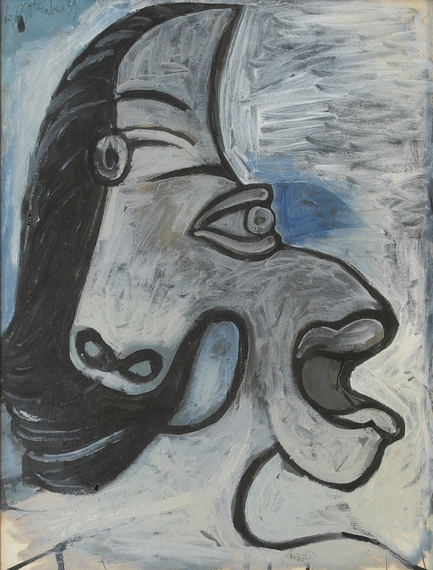

The exhibit is threefold: the politically engaged writer, poet, and intellectual was an avid collector of objects--primitive sculptures from Oceania, pre-Hispanic figures from Mexico, Inuit objects as well as paintings, drawings and photographs that he acquired or was given by his friends. Here, the curators, Laurent Guillaut and Constance Krebs (who runs the official André Breton website) recreated Breton's famous desk and wall that was in his cluttered apartment in Paris' rue Fontaine with a 360 degree panoramic film taken from photographs. The wall behind his desk was considered a work of art in itself and was donated to the Centre Pompidou museum in 2003. Guillaut and Krebs borrowed the original objects and artwork from a variety of sources including Breton's daughter, Aube Breton-Elléouët. The huge collection, which included thousands of books and works of art, was dispersed in an auction in 2003 after the French government balked at buying the lot. (Luckily the entire contents of Breton's apartment were captured on film and are available on the Breton website.) Treasures in the show include a self-portrait by Frida Kahlo in an alluring, shell-encrusted frame, an Edvard Munch engraving, a "rayograph" by Man Ray, and a portrait of the photographer Dora Maar, that Picasso painted for Breton in 1940.

The exhibit also commemorates the Citizens of the World movement founded in 1949 by the American peace activist and former World War II pilot, Garry Davis. Davis' movement, which envisioned a world without borders and passports, boasted 750,000 members, of which André Breton and others--Jean-Paul Sartre, André Gide and Albert Camus. The city of Cahors joined the movement, declaring itself a "world" city in 1949 and placed one of the first milestones--the plan was for milestones to circle the world--on a road that was designated the Route Mondiale No. 1 (World road). There are video recordings of Davis and Breton speaking to crowds, newspaper clippings and an exhibition of black and white photographs commissioned by the museum on the subject of the World road. Nadia Benchallal, the photographer, followed the winding road along the river, and said her film photography images were a road trip that sought to superimpose today's territory to yesterday's world.

The third part of the exhibit that provides a link to the others and explains why the Cahors area was so important to Breton; focuses on the nearby medieval village of Saint-Cirq-Lapopie where Breton, enchanted, settled in 1951. His father helped him buy a house thus enabling him to fulfill his dream of assembling his surrealist friends where they exchanged and debated ideas, played, created and foraged together in antique shops to furnish the house.

On the ground floor of the museum a room is filled with lovely works by post-impressionist painter Henri Martin, including views of Saint-Cirq-Lapopie and André Breton's future house, the Auberge des Mariniers. One floor up, Laurent Guillaut assembled a number of objects from Breton's home in Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, including a bowl of agate stones that Breton and his surrealist friends liked to collect along the Lot river and which he wrote about in a text called "Language of Stones":

Last year when we approached, under a light rain, a bed of stones that we had not yet explored along the Lot, the suddenness with which several agates, which had an unusual beauty for the region "caught our eyes", convinced me that every further step would offer more beautiful ones and over a minute I had the perfect illusion to set foot in earthly paradise.

Besides bringing together many rare and extraordinary objects and art, the exhibit gives us the opportunity to remember, in these violent times, an avant-garde, creative thinker who used art to protest war.

![2014-10-16-Andre_Breton_et_Max_Ernst_devantlabornedelaroutemondialeaCahorsphotoXassociationAtelier_Andre_Breton.JPG]()

![2014-10-16-Frida_Kahlo__Autoportrait_1938__Benjamin_Krebs.jpg]()

![2014-10-16-Pablo_Picasso_Tete_ou_Portrait_deDoraMaar1939BenjaminKrebs.jpg]()

The exhibit is threefold: the politically engaged writer, poet, and intellectual was an avid collector of objects--primitive sculptures from Oceania, pre-Hispanic figures from Mexico, Inuit objects as well as paintings, drawings and photographs that he acquired or was given by his friends. Here, the curators, Laurent Guillaut and Constance Krebs (who runs the official André Breton website) recreated Breton's famous desk and wall that was in his cluttered apartment in Paris' rue Fontaine with a 360 degree panoramic film taken from photographs. The wall behind his desk was considered a work of art in itself and was donated to the Centre Pompidou museum in 2003. Guillaut and Krebs borrowed the original objects and artwork from a variety of sources including Breton's daughter, Aube Breton-Elléouët. The huge collection, which included thousands of books and works of art, was dispersed in an auction in 2003 after the French government balked at buying the lot. (Luckily the entire contents of Breton's apartment were captured on film and are available on the Breton website.) Treasures in the show include a self-portrait by Frida Kahlo in an alluring, shell-encrusted frame, an Edvard Munch engraving, a "rayograph" by Man Ray, and a portrait of the photographer Dora Maar, that Picasso painted for Breton in 1940.

The exhibit also commemorates the Citizens of the World movement founded in 1949 by the American peace activist and former World War II pilot, Garry Davis. Davis' movement, which envisioned a world without borders and passports, boasted 750,000 members, of which André Breton and others--Jean-Paul Sartre, André Gide and Albert Camus. The city of Cahors joined the movement, declaring itself a "world" city in 1949 and placed one of the first milestones--the plan was for milestones to circle the world--on a road that was designated the Route Mondiale No. 1 (World road). There are video recordings of Davis and Breton speaking to crowds, newspaper clippings and an exhibition of black and white photographs commissioned by the museum on the subject of the World road. Nadia Benchallal, the photographer, followed the winding road along the river, and said her film photography images were a road trip that sought to superimpose today's territory to yesterday's world.

The third part of the exhibit that provides a link to the others and explains why the Cahors area was so important to Breton; focuses on the nearby medieval village of Saint-Cirq-Lapopie where Breton, enchanted, settled in 1951. His father helped him buy a house thus enabling him to fulfill his dream of assembling his surrealist friends where they exchanged and debated ideas, played, created and foraged together in antique shops to furnish the house.

On the ground floor of the museum a room is filled with lovely works by post-impressionist painter Henri Martin, including views of Saint-Cirq-Lapopie and André Breton's future house, the Auberge des Mariniers. One floor up, Laurent Guillaut assembled a number of objects from Breton's home in Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, including a bowl of agate stones that Breton and his surrealist friends liked to collect along the Lot river and which he wrote about in a text called "Language of Stones":

Last year when we approached, under a light rain, a bed of stones that we had not yet explored along the Lot, the suddenness with which several agates, which had an unusual beauty for the region "caught our eyes", convinced me that every further step would offer more beautiful ones and over a minute I had the perfect illusion to set foot in earthly paradise.

Besides bringing together many rare and extraordinary objects and art, the exhibit gives us the opportunity to remember, in these violent times, an avant-garde, creative thinker who used art to protest war.