This commentary on artists from Iran showing in New York was prompted by the exhibition, Portraits: Reflections by Emerging Iranian Artists, curated by Roya Khadjavi Heidari and Massoud Nader and on view from September 17 through 29, 2014 at the Rogue Space Chelsea, 508 West 26th St. New York, NY 10011. Although up for only two weeks, the exhibition and online catalogue represent a large contingent of Iranian artists now either living or visiting New York. The space promises to be a bridge for Western audiences to the contemporary artists perpetuating the vibrant culture and civilization known to have produced some of the world's most illustrious and lasting developments in art, literature and architecture for four millennia. View the online catalogue here.

![2014-10-10-TirafkanAshura.jpg]()

If the artists pouring into New York from Iraq over the last decade are any indication, the period of rapprochement between the US and Iran has been ongoing long before the press came to notice. Of course, the reality is that, despite the recent thawing of relations, progress between the US and Iranian governments remains stalled over Iran's present and future nuclear capacity and its human rights violations -- to the point that President Obama refused to meet with President Hassan Rouhani during his New York visit this week to speak at The United Nations. It seemed a telling syncronicity that just a week before Rouhani's visit, the exhibition Portraits: Reflections by Emerging Iranian Artists testified to a key point made by Rouhani in his UN Speech -- that the intransigence of the Iranian mullahs and government toward democratic reform has caused the nation to suffer a severe brain drain to the West.

![2014-10-04-Pourhosseinni.jpg]()

If the small but diverse selection of artists in the exhibition, Portraits: Reflections of Iranian Artists is indication, the drain of painters and photographers (and the show's one sculptor) is significant and visionary, even if most of them have yet to make their mark on the New York art scene. But then the art galleries and institutions, though responsive to few key artists from Iran, have hardly been showcasing Iranian art in their restraint of exhibitions. After the Asia Society's disappointingly conservative, even academic, spring 2014 selection of Iranian art, and the too-infrequent selections of contemporary art exhibited in the small chamber set aside for Iranian art in The Metropolitan Museum's Islamic Wing, the Rogue Gallery finally offered satiation for the growing appetite of New Yorkers craving compelling contemporary art from Iran.

![2014-10-08-FaribaHajamadiRelease.jpg]()

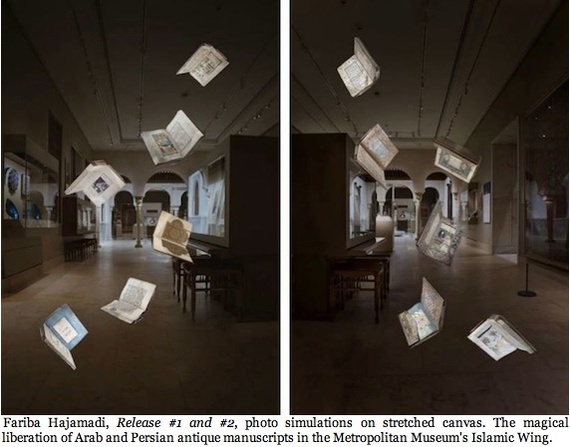

If the floodgate in New York for emerging Iranian artists is only just opening, we have at least been fortunate to receive a trickle of Iranian artists since the 1980s. Even as the West read in the 1980s about the nascent post-revolutionary, fiercely isolationist Iran, a decade when Americans in particular were still raw from its interminably endless humiliation and horror during the 1979-80 hostage crisis, New York's reception to vital contemporary Iranian Art began to open itself to a trickle of artist emigres. In the mid 1980s, Fariba Hajamadi began showing her photography critical of the cultural and ethnic biases of museums and galleries in New York, Paris and other Western cosmopolitan centers. Hajamadi was one of the first emigres from the Middle East through whose eyes Western audiences for art saw evidence that our own art and cultural institutions shave historically been sites of insidious culturocentric perpetuation. Hajamadi's conceptualist approach to photographing institutions put her in the role of the keen if polite observer who documents institutions which, like photography itself, alter the picture to emphasize how images alter one culture's perception and representation of another culture's history. From there Hajamadi insinuates how both the photographic context and the museum display of a culture's art and artifacts is subject to different readings while creating artificial memories that become particularly prone to political manipulations in the "representation" of other cultures and their histories.

![2014-10-08-ShirinNeshat.jpg]()

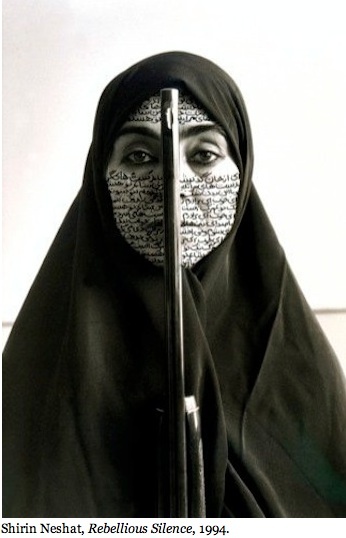

In the 1990s, as the art of American political and cultural identity proliferated, Shirin Neshat dramatically politicized the gallery and the museum context by the introduction of her graphic, black and white Women of Allah photography series to Western audiences, which proved stunningly and provocatively to depict both singular and groups of Iranian women in chadors. The series' simultaneously-liberating and alarming imagery of strong, resourceful women -- some brandishing guns in their taking of arms during the Iran-Iraq Wars; others with skin covered by Farsi script that few people outside Iran can read -- tore open the Western gallery and institutional purview. Neshat did no less than spectacularly and ubiquitously supply Western audiences their first indigenous look at hijab at work in the open, graphically and dramatically tracing the divide between men and women, Islam and the West, Sharia law and feminism, even Iranian feminism from Western feminism. (See my feature about Shirin Neshat's art on Huffington Post.)

![2014-10-08-ShojaAzariNew.jpg]()

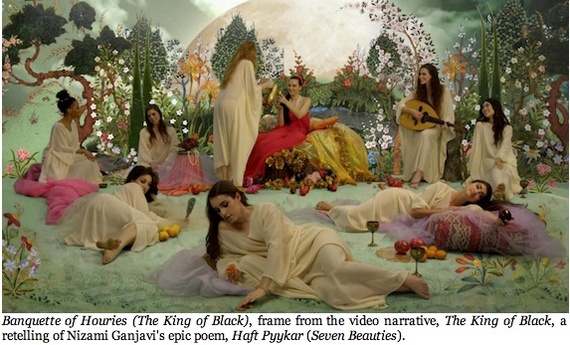

In the last decade, Neshat's husband and film collaborator, Shoja Azarii, has also made strides in New York, chiefly with his captivating video-projections retelling such Iranian classics as Nizami Ganjavi's epic poem, Haft Pyykar (Seven Beauties). His painting simulations evoke the contemporary nomadic conflation of opposites in both embodying criticism of Western Orientalism while simultaneously mimicking and recontextualizing the picturesque and imaginative European Orientalist paintings of the 18th and 19th centuries that post-colonialist thinkers like Edward Said found to be largely ethnocentric inventions and formulas for perpetuating European domination over North African and Middle Eastern nations and societies. (More commentary on Soja Azari is included in my summary of shows for 2013 on Huffington Post.)

![2014-10-08-AliBanisadr.jpg]()

And there is Iranian emigre, Ali Banisadr, who over the last decade has almost single-handedly revitalized expressionist abstraction on exhibit in Manhattan galleries with a body of work that fuses lessons the painter learned from his studies of the Islamic miniature, Renaissance apocalyptic painting, and the most formalist of Euro-American expressionism. The resultant pictorial arrangements leap spectacularly across our cognitive and cultural representations of great expanses of geography, time, and ideology while retaining traces of the human figure in fields of non-objective gestural markings that emulate the rhythmic patterns of battle scenes or great gatherings of humanity depicted on some accelerated visual frequency that registers as a great blur or trail of human figurative energy, while emulating European and Middle Eastern masters of high painting styles and iconography. (More commentary of Ali Banisadr can be found here on Huffington Post.)

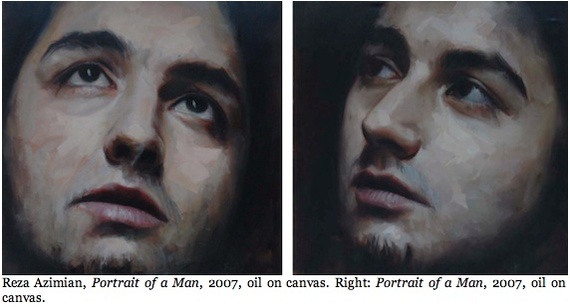

![2014-10-04-ReezaAzimian.jpg]()

With these four singular Iranian artists paving the way (none of whom were included in the show), it should be no surprise that so much of the work in Portraits takes on political dissent and the politics of sexual and gender identity as its context and content, given that the political art of dissent has since the 1960s become the single most recognizable and ubiquitous form of art made globally. And like the political art of such nations as Mexico, North Ireland, Israel/Palestine, Argentina, Chile, Egypt, South Africa, Iraq, the Balkans, Cuba, China, Japan and the U.S., the Iranian contingent favors figurative art as its chief formal and cultural idiom. The good news is that by and large the Iranian artists shun the Social Realism that had since the 1930s become de riguer to more populist political left political art around the world. Irony is amply in supply and a discreet conceptualism is salient, often to the point of defining the content and context of the work. Magical Realism, a stylization we know primarily from Latin American, Indian Arab and Iranian modern literature and film, is also a favored trope for its hybridization of multiple planes of reality that without the "magical" link could not coexist, nor could the hidden meanings be recognized or understood.

![2014-10-10-Farsad.jpg]()

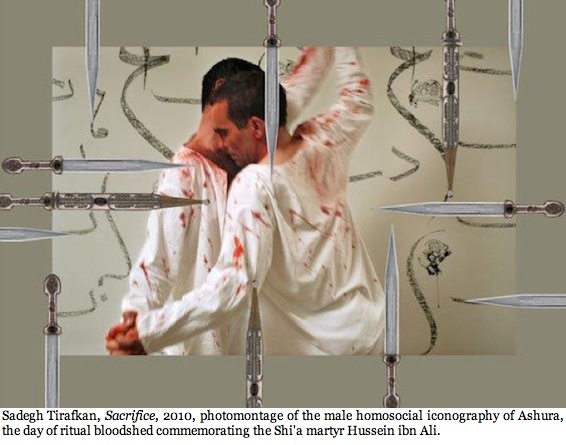

Not all the artists have left Iran permanently. Sadegh Tirafkan, among the most salient Iranian of the artists in the show, still lives in Tehran. In his intent to remain true to the Iranian heritage and sensibility, Tirafkan may also be the most provocative to non-Muslim viewers. I've opened this commentary with a photomontage from his Sacrifice series which brings a sense of intimacy, if not eroticism, to the male homosocial Shi'a Muslim ritual of voluntary bloodletting on the Day of Ashura, the yearly commemoration of the martyrdom of Hussein ibn Ali in 680 CE (61 AH of the Islamic calendar). The work is a counterpoint in offering a more demure depiction of a ritual that has been sensationalized by Western photojournalism focusing in on only the more extremist and publicly overweight expressions of the Shi'a holy day.

![2014-10-04-BidarianNew.jpg]()

Tirafkan's work is the show's semaphore to Western critics and audiences, signalling loud and clear just how greatly we require more work by the new wave of Iranian artists to learn about the ideological and conceptual codification of the diaspora before appraising it critically, especially as so much of it is expressed as an idiom that looks longingly back at a nation, and those beloved, left reluctantly behind. Although the artists convey the Iranian political climate to be stifling, even deadly, they also insinuate that the potentially fertile and expansive subcultural optimism spreading fantasies of a democratic Iran is ready for another wave of dissent, however personal and discreet, heady, and/or violent. Sadly, as Americans and Westerners, we no doubt miss much of the nuance and innuendo conveyed by the artists, which is why I defer now to the curators, Roya Khadjavi Heidari and Massoud Nader, to tell us to what extent the work we see is a testament to the artists' determination and courage, and in some cases even more to the courage and determination of those Iranian subjects they left behind and depict.

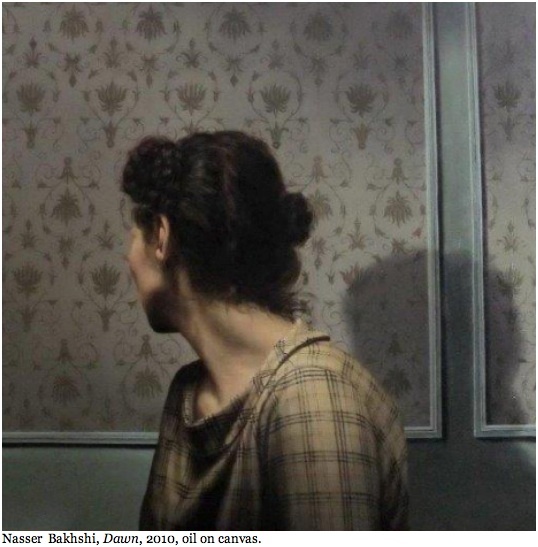

![2014-10-04-Bakhshi.jpg]()

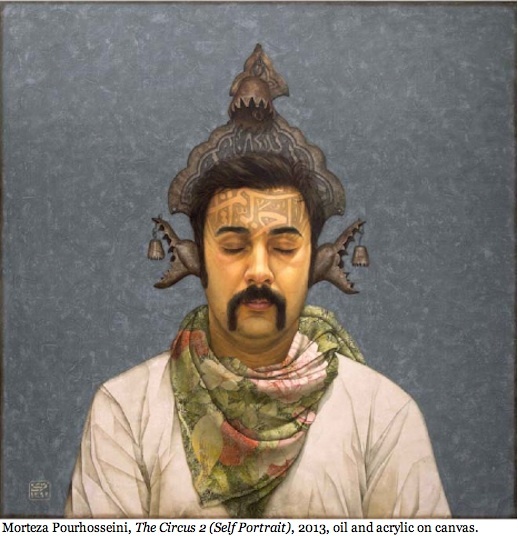

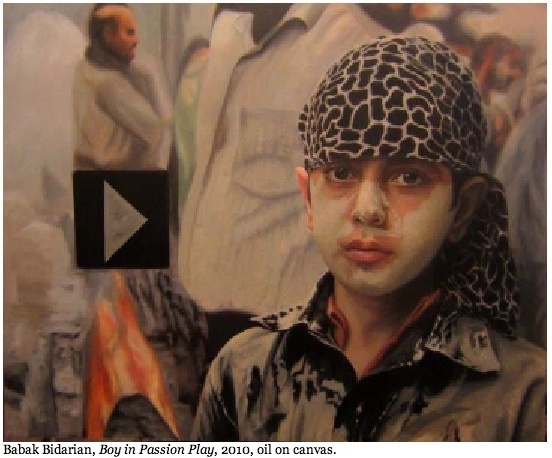

The strongest work in the show consisted of paintings of remarkable pictorial and temporal encapsulation -- that is they conveyed the steep Persian history and Islamic social code bearing down on the contemporary Iranian individual and society in both matters secular and spiritual. Others clearly are compelled to study, re-enact, and represent the 1979 Revolution before they move on to represent what Iran and Iranians have become and yet might become. As the curators, Heidari and Nader point out to those of us new to the iconography of modern Iran and historic Persia, the history that shapes the artists in their daily engagements, also defines their estrangements from the Iran of the ruling mullahs and secular oligarchy. They tell us that Sadeq TIRAFKHAN literally "wrestles with the notion of sacrifice" as he depicts the passion inherent to the ancient male homosocial ritualization of Iran's largely Shia population. Morteza POURHOSSEINI's Circus Series, we are told portrays the artist with a forehead bearing "the stamp of Quranic invocations; his back is ready for the sword and shield of tradition." The boy with the bandana in the painting of a video, Boy in Passion Play, 2013, by Babak BIDARIAN, "is looking directly at the painter, who can only be an observer in the reenactment of a liturgical drama, whose meaning the artist is not privy to".

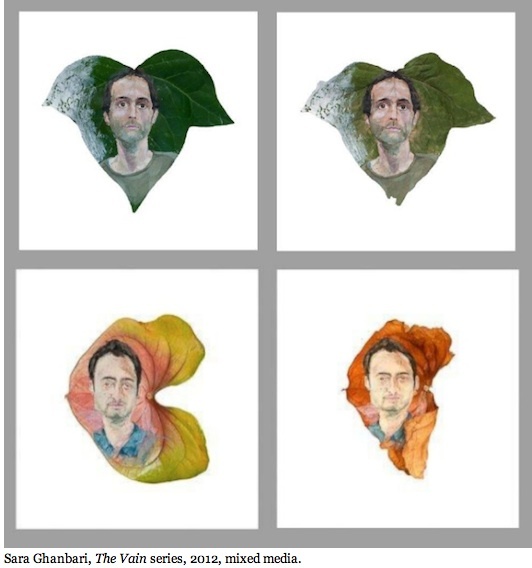

![2014-10-04-NewGhanberi.jpg]()

From hereon I quote or paraphrase the online catalogue by Heidari and Nader.

"The sense of estrangement from society, or the incapacity to come to terms with the conflict between the self and other, often more powerful, social forces, suffuses these works. In her Rock, Paper, Scissors series (2006) Jinoos TAGHIZADEH is tracing the political roots of his estrangement by studying the pages of newspapers in the wake of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The indeterminate nature of the political landscape following the revolutionary moment is depicted through substitution of the original front-page photographs of newspapers of the time by lenticular images that suggest other possible historical outcomes. Somewhere in the middle of these newspaper pages we come upon a picture of the artist at the age of seven, beneath which appears an announcement of her having been lost since the revolution's victory."

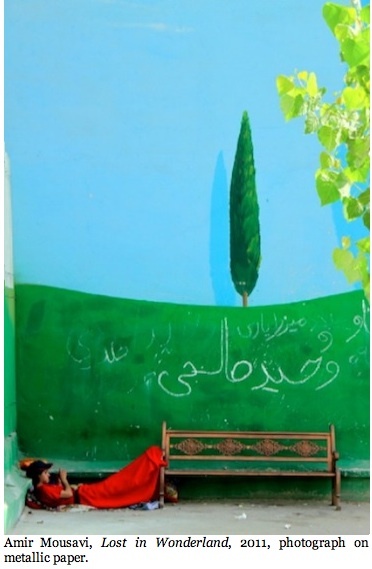

![2014-10-04-Mousavi.jpg]()

"The modern middle class, whom the artists in this exhibit by and large belong to, has had a tumultuous relationship with the state and with society at large. It helped to set in motion the Revolution of 1979, but was soon kept at bay by an emerging ruling class who took the political center stage through contentious means. Every decade since then has offered the middle class reasons to insert themselves into or dissociate from politics; to turn their backs on or to try to understand the nature of the society they live in."

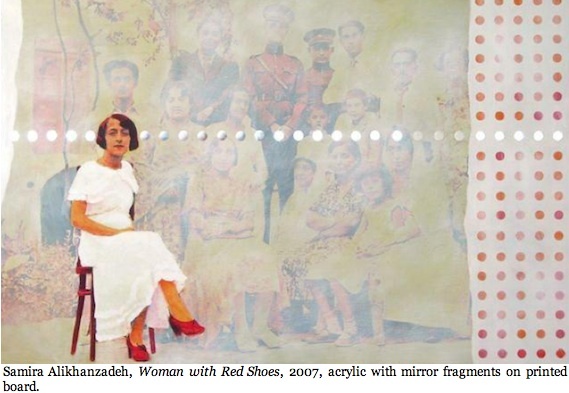

![2014-10-10-SamiraRedShoes.jpg]()

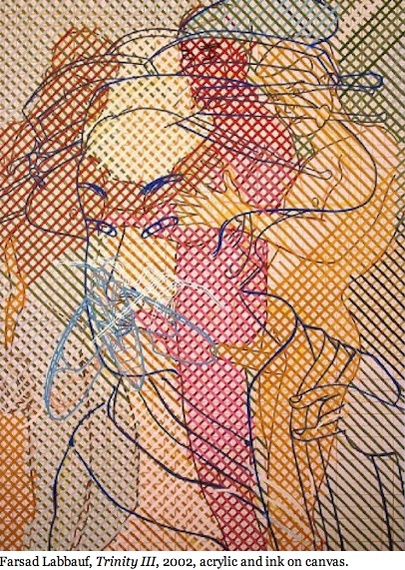

"The 2009 presidential election (almost all of these works were completed afterwards) marks the re-entry of the middle class into politics. The desire for the middle class to represent itself traps Alishia Morassaie's My 9 cm Friends 5 in a bottle; occupies Nasser Bakhshi's When We Were Together with the same self-reflexive space; spins Bahar BEHBAHANI in Proceeding, 2011, in a dizzying, upside-down awareness of surroundings; summons ghosts from the past in Samira ALIKHANZADEH's The Wedding, 2010); prances Dariush GHARAHZAD's Girl with Red Scarf, 2006, in an attire not of its choosing; crumpled and contorted Mohammad HAMZEH's The Accountant, 2009, in its portrayal; at once hides and reveals the sexuality of Hossein EDALATKHAH's My Life, My Body, My Bio series, 2009; outlines Farshad LABBAUF's politic in Trinity III, 2013; or simply stands in Arash SEDAGHAKISH's Untitled, from the University Students series, 2011."

![2014-10-10-RadaieSclpture.jpg]()

"They may appear apolitical to the viewer at first, but whether, through self-representation, recognition, or assertion, these works challenge the status quo. Some offer a critical view of the dominant issues of the day. The rich symbolism of The Lion and the Sun, 2010, by Mohsen AHMADVAND, creates a mutant creature that stands at the apex of middle class national utopianism. People in Naghmeh GHASSEMLOO's photographs (from the Navab series, 2011, seem to be ghosts inhabiting a sphere that is in the process of dissolution. The donkeys in Majid BIGLARI's Kharkhouneh, 2011, speaks to the ignorance that the artist sees pervading Iranian society today -- from the masses below to the rulers above -- and possibly including his own middle class. The Children's Program installation of Mojtaba AMINI is a scathing criticism of the punitive juridical approach of the state as it relates to delinquent children. Could the dorsal portraits of Nasser BAKHSHI be a way for the artist to remain within, but with his back turned on society?"

![2014-10-10-Behbahani.jpg]()

"These works recognize the multifaceted nature of the society they were conceived in. Perhaps because of this recognition, they exhibit an estrangement from a ruling order that delegitimizes their ways of being-in-the-world. As such, this particular middle class is not out to universalize its mode of existence but is interested in expression and self-representation as a strategy for social legitimation and insertion."

![2014-10-10-Taghizadeh.jpg]()

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on Facebook.

If the artists pouring into New York from Iraq over the last decade are any indication, the period of rapprochement between the US and Iran has been ongoing long before the press came to notice. Of course, the reality is that, despite the recent thawing of relations, progress between the US and Iranian governments remains stalled over Iran's present and future nuclear capacity and its human rights violations -- to the point that President Obama refused to meet with President Hassan Rouhani during his New York visit this week to speak at The United Nations. It seemed a telling syncronicity that just a week before Rouhani's visit, the exhibition Portraits: Reflections by Emerging Iranian Artists testified to a key point made by Rouhani in his UN Speech -- that the intransigence of the Iranian mullahs and government toward democratic reform has caused the nation to suffer a severe brain drain to the West.

If the small but diverse selection of artists in the exhibition, Portraits: Reflections of Iranian Artists is indication, the drain of painters and photographers (and the show's one sculptor) is significant and visionary, even if most of them have yet to make their mark on the New York art scene. But then the art galleries and institutions, though responsive to few key artists from Iran, have hardly been showcasing Iranian art in their restraint of exhibitions. After the Asia Society's disappointingly conservative, even academic, spring 2014 selection of Iranian art, and the too-infrequent selections of contemporary art exhibited in the small chamber set aside for Iranian art in The Metropolitan Museum's Islamic Wing, the Rogue Gallery finally offered satiation for the growing appetite of New Yorkers craving compelling contemporary art from Iran.

If the floodgate in New York for emerging Iranian artists is only just opening, we have at least been fortunate to receive a trickle of Iranian artists since the 1980s. Even as the West read in the 1980s about the nascent post-revolutionary, fiercely isolationist Iran, a decade when Americans in particular were still raw from its interminably endless humiliation and horror during the 1979-80 hostage crisis, New York's reception to vital contemporary Iranian Art began to open itself to a trickle of artist emigres. In the mid 1980s, Fariba Hajamadi began showing her photography critical of the cultural and ethnic biases of museums and galleries in New York, Paris and other Western cosmopolitan centers. Hajamadi was one of the first emigres from the Middle East through whose eyes Western audiences for art saw evidence that our own art and cultural institutions shave historically been sites of insidious culturocentric perpetuation. Hajamadi's conceptualist approach to photographing institutions put her in the role of the keen if polite observer who documents institutions which, like photography itself, alter the picture to emphasize how images alter one culture's perception and representation of another culture's history. From there Hajamadi insinuates how both the photographic context and the museum display of a culture's art and artifacts is subject to different readings while creating artificial memories that become particularly prone to political manipulations in the "representation" of other cultures and their histories.

In the 1990s, as the art of American political and cultural identity proliferated, Shirin Neshat dramatically politicized the gallery and the museum context by the introduction of her graphic, black and white Women of Allah photography series to Western audiences, which proved stunningly and provocatively to depict both singular and groups of Iranian women in chadors. The series' simultaneously-liberating and alarming imagery of strong, resourceful women -- some brandishing guns in their taking of arms during the Iran-Iraq Wars; others with skin covered by Farsi script that few people outside Iran can read -- tore open the Western gallery and institutional purview. Neshat did no less than spectacularly and ubiquitously supply Western audiences their first indigenous look at hijab at work in the open, graphically and dramatically tracing the divide between men and women, Islam and the West, Sharia law and feminism, even Iranian feminism from Western feminism. (See my feature about Shirin Neshat's art on Huffington Post.)

In the last decade, Neshat's husband and film collaborator, Shoja Azarii, has also made strides in New York, chiefly with his captivating video-projections retelling such Iranian classics as Nizami Ganjavi's epic poem, Haft Pyykar (Seven Beauties). His painting simulations evoke the contemporary nomadic conflation of opposites in both embodying criticism of Western Orientalism while simultaneously mimicking and recontextualizing the picturesque and imaginative European Orientalist paintings of the 18th and 19th centuries that post-colonialist thinkers like Edward Said found to be largely ethnocentric inventions and formulas for perpetuating European domination over North African and Middle Eastern nations and societies. (More commentary on Soja Azari is included in my summary of shows for 2013 on Huffington Post.)

And there is Iranian emigre, Ali Banisadr, who over the last decade has almost single-handedly revitalized expressionist abstraction on exhibit in Manhattan galleries with a body of work that fuses lessons the painter learned from his studies of the Islamic miniature, Renaissance apocalyptic painting, and the most formalist of Euro-American expressionism. The resultant pictorial arrangements leap spectacularly across our cognitive and cultural representations of great expanses of geography, time, and ideology while retaining traces of the human figure in fields of non-objective gestural markings that emulate the rhythmic patterns of battle scenes or great gatherings of humanity depicted on some accelerated visual frequency that registers as a great blur or trail of human figurative energy, while emulating European and Middle Eastern masters of high painting styles and iconography. (More commentary of Ali Banisadr can be found here on Huffington Post.)

With these four singular Iranian artists paving the way (none of whom were included in the show), it should be no surprise that so much of the work in Portraits takes on political dissent and the politics of sexual and gender identity as its context and content, given that the political art of dissent has since the 1960s become the single most recognizable and ubiquitous form of art made globally. And like the political art of such nations as Mexico, North Ireland, Israel/Palestine, Argentina, Chile, Egypt, South Africa, Iraq, the Balkans, Cuba, China, Japan and the U.S., the Iranian contingent favors figurative art as its chief formal and cultural idiom. The good news is that by and large the Iranian artists shun the Social Realism that had since the 1930s become de riguer to more populist political left political art around the world. Irony is amply in supply and a discreet conceptualism is salient, often to the point of defining the content and context of the work. Magical Realism, a stylization we know primarily from Latin American, Indian Arab and Iranian modern literature and film, is also a favored trope for its hybridization of multiple planes of reality that without the "magical" link could not coexist, nor could the hidden meanings be recognized or understood.

Not all the artists have left Iran permanently. Sadegh Tirafkan, among the most salient Iranian of the artists in the show, still lives in Tehran. In his intent to remain true to the Iranian heritage and sensibility, Tirafkan may also be the most provocative to non-Muslim viewers. I've opened this commentary with a photomontage from his Sacrifice series which brings a sense of intimacy, if not eroticism, to the male homosocial Shi'a Muslim ritual of voluntary bloodletting on the Day of Ashura, the yearly commemoration of the martyrdom of Hussein ibn Ali in 680 CE (61 AH of the Islamic calendar). The work is a counterpoint in offering a more demure depiction of a ritual that has been sensationalized by Western photojournalism focusing in on only the more extremist and publicly overweight expressions of the Shi'a holy day.

Tirafkan's work is the show's semaphore to Western critics and audiences, signalling loud and clear just how greatly we require more work by the new wave of Iranian artists to learn about the ideological and conceptual codification of the diaspora before appraising it critically, especially as so much of it is expressed as an idiom that looks longingly back at a nation, and those beloved, left reluctantly behind. Although the artists convey the Iranian political climate to be stifling, even deadly, they also insinuate that the potentially fertile and expansive subcultural optimism spreading fantasies of a democratic Iran is ready for another wave of dissent, however personal and discreet, heady, and/or violent. Sadly, as Americans and Westerners, we no doubt miss much of the nuance and innuendo conveyed by the artists, which is why I defer now to the curators, Roya Khadjavi Heidari and Massoud Nader, to tell us to what extent the work we see is a testament to the artists' determination and courage, and in some cases even more to the courage and determination of those Iranian subjects they left behind and depict.

The strongest work in the show consisted of paintings of remarkable pictorial and temporal encapsulation -- that is they conveyed the steep Persian history and Islamic social code bearing down on the contemporary Iranian individual and society in both matters secular and spiritual. Others clearly are compelled to study, re-enact, and represent the 1979 Revolution before they move on to represent what Iran and Iranians have become and yet might become. As the curators, Heidari and Nader point out to those of us new to the iconography of modern Iran and historic Persia, the history that shapes the artists in their daily engagements, also defines their estrangements from the Iran of the ruling mullahs and secular oligarchy. They tell us that Sadeq TIRAFKHAN literally "wrestles with the notion of sacrifice" as he depicts the passion inherent to the ancient male homosocial ritualization of Iran's largely Shia population. Morteza POURHOSSEINI's Circus Series, we are told portrays the artist with a forehead bearing "the stamp of Quranic invocations; his back is ready for the sword and shield of tradition." The boy with the bandana in the painting of a video, Boy in Passion Play, 2013, by Babak BIDARIAN, "is looking directly at the painter, who can only be an observer in the reenactment of a liturgical drama, whose meaning the artist is not privy to".

From hereon I quote or paraphrase the online catalogue by Heidari and Nader.

"The sense of estrangement from society, or the incapacity to come to terms with the conflict between the self and other, often more powerful, social forces, suffuses these works. In her Rock, Paper, Scissors series (2006) Jinoos TAGHIZADEH is tracing the political roots of his estrangement by studying the pages of newspapers in the wake of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. The indeterminate nature of the political landscape following the revolutionary moment is depicted through substitution of the original front-page photographs of newspapers of the time by lenticular images that suggest other possible historical outcomes. Somewhere in the middle of these newspaper pages we come upon a picture of the artist at the age of seven, beneath which appears an announcement of her having been lost since the revolution's victory."

"The modern middle class, whom the artists in this exhibit by and large belong to, has had a tumultuous relationship with the state and with society at large. It helped to set in motion the Revolution of 1979, but was soon kept at bay by an emerging ruling class who took the political center stage through contentious means. Every decade since then has offered the middle class reasons to insert themselves into or dissociate from politics; to turn their backs on or to try to understand the nature of the society they live in."

"The 2009 presidential election (almost all of these works were completed afterwards) marks the re-entry of the middle class into politics. The desire for the middle class to represent itself traps Alishia Morassaie's My 9 cm Friends 5 in a bottle; occupies Nasser Bakhshi's When We Were Together with the same self-reflexive space; spins Bahar BEHBAHANI in Proceeding, 2011, in a dizzying, upside-down awareness of surroundings; summons ghosts from the past in Samira ALIKHANZADEH's The Wedding, 2010); prances Dariush GHARAHZAD's Girl with Red Scarf, 2006, in an attire not of its choosing; crumpled and contorted Mohammad HAMZEH's The Accountant, 2009, in its portrayal; at once hides and reveals the sexuality of Hossein EDALATKHAH's My Life, My Body, My Bio series, 2009; outlines Farshad LABBAUF's politic in Trinity III, 2013; or simply stands in Arash SEDAGHAKISH's Untitled, from the University Students series, 2011."

"They may appear apolitical to the viewer at first, but whether, through self-representation, recognition, or assertion, these works challenge the status quo. Some offer a critical view of the dominant issues of the day. The rich symbolism of The Lion and the Sun, 2010, by Mohsen AHMADVAND, creates a mutant creature that stands at the apex of middle class national utopianism. People in Naghmeh GHASSEMLOO's photographs (from the Navab series, 2011, seem to be ghosts inhabiting a sphere that is in the process of dissolution. The donkeys in Majid BIGLARI's Kharkhouneh, 2011, speaks to the ignorance that the artist sees pervading Iranian society today -- from the masses below to the rulers above -- and possibly including his own middle class. The Children's Program installation of Mojtaba AMINI is a scathing criticism of the punitive juridical approach of the state as it relates to delinquent children. Could the dorsal portraits of Nasser BAKHSHI be a way for the artist to remain within, but with his back turned on society?"

"These works recognize the multifaceted nature of the society they were conceived in. Perhaps because of this recognition, they exhibit an estrangement from a ruling order that delegitimizes their ways of being-in-the-world. As such, this particular middle class is not out to universalize its mode of existence but is interested in expression and self-representation as a strategy for social legitimation and insertion."

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on Facebook.