There is a great paradox in contemporary poetry.

On the one hand, poetry seems to be dwindling -- in bookstore shelves and traditional academic curricula -- so much so that it has become fashionable for journalists to frequently declare it dead. On the other hand, I have but to scroll through my social media feeds to witness an eruption of poetry being written and published online.

Likewise, an offering like Al Filreis' Modern Poetry online course has attracted more than 100,000 students eager to read and learn from great poets of the past. Furthermore, as a poet I know that even though the overall fan base for poetry may have dwindled since the advent of the Internet, that same technology allows me to connect with global audiences many times the size of what some of our most respected poets enjoyed as regional audiences one hundred years ago.

So it would seem that poetry is dying in the real world, only to be reborn into a kind of "Invisible Golden Age" online.

My own response to this paradox is equally dualistic. I acknowledge that poetry may never go mainstream in my lifetime, and aspire primarily for the respect of respectable peers. Yet at the same time, I work hard to bring poetry to new audiences, in person and online. In that vein, I have been gathering my thoughts about the fact that so many people are now reading and writing poems, yet poetry is still perceived as a floundering art. Really, how can this be?

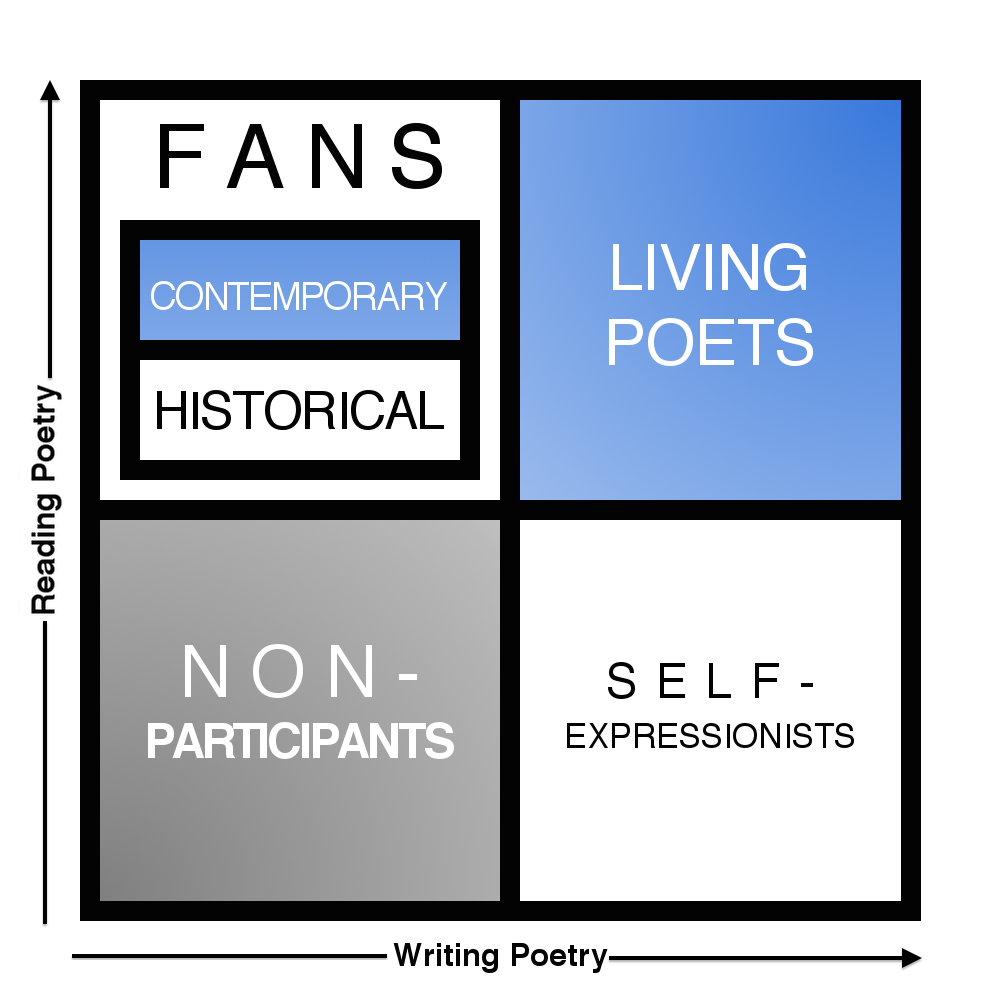

The following diagram illustrates how I see people engaging with poetry today.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The boxes in blue represent the behaviors most likely to help usher us out of this "Invisible Golden Age" into, well, a visible one -- that is, reading contemporary poetry as a fan and both reading and writing it as a poet.

It is pretty easy to see why the health and longevity of the art depends on these things happening. So how do we encourage such behavior?

Think of the diagram as a board game. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is help usher people from the gray areas into the white, and from the white areas into the blue. Fostering some appreciation of historical poetry, as well as providing some early creative outlet for trying one's hand at writing the stuff, is usually best begun in primary school. Initiatives like California Poets in the Schools do a fine job of this. They move people into the white.

From here, the sheer volume of poetry being written, and the speed at which it races around online and even in print, can be daunting for new readers. What poets who write much and read little really need are mentors -- poets who can read what they are writing and say, "Here, try this established contemporary poet. You might learn something from them about the kind of poem you are trying to write." MFA programs are one place where this happens, but workshop groups and tame poet-friends can do this too.

Likewise, readers of historical poetry need encouragement, based on their current tastes, to branch into contemporary poets. Like John Donne? Try Christian Wiman. John Keats? Try Li-Young Lee. For me, this started at university, but it is really never too early or too late to try contemporary poetry.

We may not be able to hit a "home run" by ushering people straight from the grey zone of non-participation into becoming overnight poets in the blue. Yet by first opening the doors to reading and writing poetry of any kind, then by acknowledging that contemporary poetry is largely a matter of taste, and trying to accommodate the tastes of newcomers with useful recommendations, we may well do our part to break contemporary poetry free of its current double-bind.

There is all kinds of evidence for the benefits of engaging more deeply with poetry -- psychologically and even physiologically. Like every other contemporary poet, I know this to be true from my own experience. If, like me, you have been looking for ways to help others to find their way to poetry, I encourage you to have a look at the board, roll the dice, and join me in playing the game.

On the one hand, poetry seems to be dwindling -- in bookstore shelves and traditional academic curricula -- so much so that it has become fashionable for journalists to frequently declare it dead. On the other hand, I have but to scroll through my social media feeds to witness an eruption of poetry being written and published online.

Likewise, an offering like Al Filreis' Modern Poetry online course has attracted more than 100,000 students eager to read and learn from great poets of the past. Furthermore, as a poet I know that even though the overall fan base for poetry may have dwindled since the advent of the Internet, that same technology allows me to connect with global audiences many times the size of what some of our most respected poets enjoyed as regional audiences one hundred years ago.

So it would seem that poetry is dying in the real world, only to be reborn into a kind of "Invisible Golden Age" online.

My own response to this paradox is equally dualistic. I acknowledge that poetry may never go mainstream in my lifetime, and aspire primarily for the respect of respectable peers. Yet at the same time, I work hard to bring poetry to new audiences, in person and online. In that vein, I have been gathering my thoughts about the fact that so many people are now reading and writing poems, yet poetry is still perceived as a floundering art. Really, how can this be?

The following diagram illustrates how I see people engaging with poetry today.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

- At the bottom left we have the non-participants, who read and write little. Often, somewhere in the course of their primary education, usually from a teacher they disliked or who disliked them, they got the message that poetry was difficult, irrelevant, or both.

- At bottom right, we have the self-expressionists, who write much but read little. Many of us entered into this phase in adolescence, when what Wordsworth called the "spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings" turned in to our first attempts at poetry.

- At top left, we have fans of poetry. Here we must distinguish between those who, like the students in Al Filreis' class, are reading historical poetry, and those who read living authors as well.

- In the upper right, we have living poets. Reading and writing are the in- and out-breath of a life steeped in poetry, and the most prolific poets I know are also among the most voracious readers.

The boxes in blue represent the behaviors most likely to help usher us out of this "Invisible Golden Age" into, well, a visible one -- that is, reading contemporary poetry as a fan and both reading and writing it as a poet.

It is pretty easy to see why the health and longevity of the art depends on these things happening. So how do we encourage such behavior?

Think of the diagram as a board game. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is help usher people from the gray areas into the white, and from the white areas into the blue. Fostering some appreciation of historical poetry, as well as providing some early creative outlet for trying one's hand at writing the stuff, is usually best begun in primary school. Initiatives like California Poets in the Schools do a fine job of this. They move people into the white.

From here, the sheer volume of poetry being written, and the speed at which it races around online and even in print, can be daunting for new readers. What poets who write much and read little really need are mentors -- poets who can read what they are writing and say, "Here, try this established contemporary poet. You might learn something from them about the kind of poem you are trying to write." MFA programs are one place where this happens, but workshop groups and tame poet-friends can do this too.

Likewise, readers of historical poetry need encouragement, based on their current tastes, to branch into contemporary poets. Like John Donne? Try Christian Wiman. John Keats? Try Li-Young Lee. For me, this started at university, but it is really never too early or too late to try contemporary poetry.

We may not be able to hit a "home run" by ushering people straight from the grey zone of non-participation into becoming overnight poets in the blue. Yet by first opening the doors to reading and writing poetry of any kind, then by acknowledging that contemporary poetry is largely a matter of taste, and trying to accommodate the tastes of newcomers with useful recommendations, we may well do our part to break contemporary poetry free of its current double-bind.

There is all kinds of evidence for the benefits of engaging more deeply with poetry -- psychologically and even physiologically. Like every other contemporary poet, I know this to be true from my own experience. If, like me, you have been looking for ways to help others to find their way to poetry, I encourage you to have a look at the board, roll the dice, and join me in playing the game.