Image courtesy of Verso Books

I have started to collect racist ephemera -- specifically directed toward Asian immigrants and their American descendants. I mean artifacts in paper such as pamphlets suggesting that Asiatic hordes would invade and take over, posters promoting the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Japanese American internment, documents containing ethnic slurs ("chink," "jap," "gook," "Chinaman," "nip," "slant-eye" and so on), and advertising featuring caricatured images. I would like to frame this propaganda and hang it. Since almost all Asian Americans whom I know, among others, have objected to this endeavor, I would like to explain the point of the project.

My purpose is to provoke. I would like to disrupt our shared comfort. The greater the upset caused by references to the past, the more intense the urge toward action for the future. Memorabilia should be saved for many reasons, and not all of it needs to inspire nostalgia for the past.

My idea comes from a story I read some time back about African Americans who have a similar hobby. It turns out there exist a few, not many but not none, African Americans who search out articles such as lawn jockeys and then display them. (Although the genealogy of the lawn jockey is disputed, the bulk of contemporary opinion deems this piece of Americana to be derogatory toward blacks.)

A colleague of mine who is Caucasian and a librarian (thus in the profession of accumulating objects) said to me she thought a person with this type of mania would appear to be very angry. My sense is just the opposite: just as people who buy a book feel they have acquired its content even if they have not in fact read the pages, a person who possesses racist art gains control over it. The idol loses its power.

As an amateur student of history, as we all are at least as to our own lives, I would like prove the past was what it was. Many people, including Asian Americans themselves, deny that Asians in American, whether new arrivals or native born, now face or for that matter have ever faced significant discrimination rooted in bigotry. They suppose "politically correct" complaints refer to only the expected adjustment that all newcomers have had to make, learning different cultural patterns, nothing more. Asian Americans are too proud to acknowledge once having been victims before becoming successful.

Hardly anybody recalls, for example, the glib xenophobia of Ogden Nash, the best-selling author of light verse (only his accompaniment to Saint-Saens's Carnival of Animals orchestral suite is recited nowadays), or Dr. Seuss, the perennial favorite among children's authors, of The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham. They have been whitewashed. Nash described "the Japanese" as "how courteous" as he "grins and bows a friendly bow; so sorry, this is my garden now." Seuss supposedly wrote Horton Hears a Who as an apology of sorts for his earlier anti-Japanese graphics (not archived within Seussville).

The few items I have purchased -- a union membership booklet with rules prohibiting the patronage of Chinese or Japanese businesses, with signed cards for attendance at meetings, and sheet music with lyrics of mock sing-song broken English -- make an argument more effectively than I ever could advance explicitly. Too rare for my means are the perfect specimens extant: political flyers that directly assert California confronts a choice whether to be reserved for white Christians, against a background depicting the horror of heathen Orientals. The talismans of racism constitute convincing proof.

The hatred of Asians was open, overt, hardcore, egregious, and unembarrassed. And it was racial. It was not simply directed at anybody coming to these shores, since some of its advocates themselves also were foreigners. Nor was it about assimilation. The demand that Asians conform to the majority was accompanied by the declaration that it would be impossible for them to do so; they remained untrustworthy, inscrutable.

I wince whenever someone who intends to be progressive declares that she has a problem with a work of art, because she deems it offensive. So much art is (or was in its own era) transgressive. Attraction and repulsion are bound together.

Those of us who care about civil rights harm our cause by implying that social justice is merely etiquette. It reduces the issue from substance to appearance. What is wrong is equated with what is ugly, and vice versa. Universal principles are overwhelmed by subjective opinions.

Our opponents, after all, take advantage of the same rhetoric. The Nazis judged modernism to be degenerate. (My own aesthetics would not surprise anyone: I am impressed by painters such as Chaim Soutine, who produced garish canvasses of beef carcasses hanging in the butcher's storeroom.)

These perceptions extend beyond tastes. Haters can claim to be offended by interracial couples holding hands. If the test were simply whether an individual has her feelings hurt, and no doubt the observer shocked by love transcending color is genuinely agitated, then their aversion about the effrontery of the act they have witnessed is not subject to refutation. Emotions cannot be denied, because they are by definition beyond reason. If creativity is judged by whether it has avoided giving offense, the racists' sensibilities deserve equal respect to Susan Sontag's essays.

There are risks to reappropriation. Irony is easily misinterpreted. A contemporary print I have purchased, by Roger Shimomura, shows two couples in a Pop Art style. In "Mix and Match," the Caucasian male and Asian female are portrayed as romantic and ideal; the Asian male and Caucasian female are portrayed as disgusting and distressed, respectively.

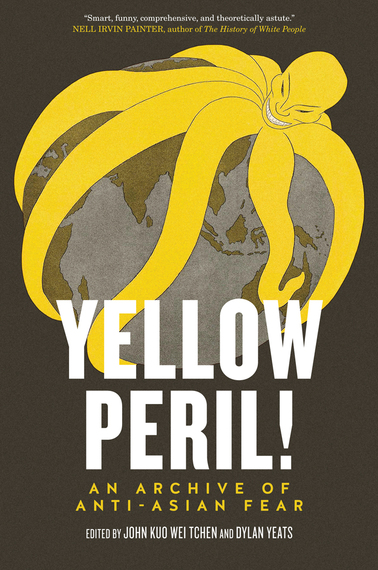

I am not alone in my enthusiasm. A few years ago, John Kuo Wei Tchen, a professor at New York University, curated an exhibition of this material. Now he, with co-author Dylan Yeats, has published a book entitled Yellow Peril: An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear. They offer details on the exclusive nature of Manifest Destiny. The new world of the nineteenth century drove toward the Pacific but stopped by protecting our side.

Yet our anxieties recur. The concerns about the decline of the West, and the rise of the East, have become acute again. There is another possibility. The differences could cease to be meaningful, as civilizations come together.

The demagogues predicted miscegenation would become the norm. They were right. We could embrace the prospect.