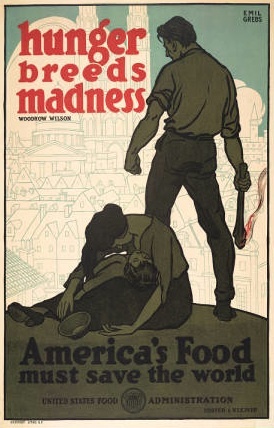

The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Garden's exhibit Your Country Calls! Posters of the First World War marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the war and includes vintage posters created to shape and influence national identity, many of which revolve around food. They are eerie and utterly fascinating. The exhibit will be on display though November 3rd. If you're in Los Angeles, don't miss it!

![2014-09-15-hungerbreedsmadness.jpg]()

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, the war already three years in and food was desperately needed to supply America's European allies. American civilians were urged to conserve food by increasing production, cutting waste and consuming foods that were plentifully available. Home cooks began substituting corn, oats or barley for wheat, molasses for sugar, and vegetable shortening for butter or lard. Peanut butter emerged as a protein substitute for meat. Meatless Mondays and Wheatless Wednesdays were encouraged and many Americans had their first vegetarian meal.

President Woodrow Wilson placed food, fuel, iron and steel under government control as war material and, as head of the United States Food Administration, Herbert Hoover sponsored an educational campaign that encouraged American farmers with the slogan, "Food can win the war." Pamphlets, posters and advertisements were produced to teach the rules of substitution and to convince Americans that eating less might improve their health. Canning, drying and preserving foods were skills treated as patriotic duties.

![2014-09-15-preserveandpotatopamphlet.jpg]()

Among the educational pamphlets the United States Food Administration published were Without Wheat, Sweets without Sugar and Potato Possibilities. The latter called the potato "a good food all the time - but especially good war time food for Americans because the use of the potato means the saving of other foods which can be more easily shipped to our own troops and our allies." Potato Balls were among the recipes listed. The following recipe is an adaptation.

![2014-09-15-potatoballs.jpg]()

Potato Balls

Native to South America, the ready and resilient potato is one of the world's most common foods.

2 pounds baking potatoes, peeled and cut into large chunks

salt and pepper

12 ounces Gruyere, cheddar or mozzarella cheese, cut into 1/3-inch dice

2 cups plain dry breadcrumbs

5 eggs

2 tablespoons Dijon mustard

vegetable oil, for frying

1. In a saucepan, cover the potatoes with cold water. Bring to a boil, salt generously and simmer over medium heat until tender, about 20 minutes. Drain, let cool and mash into a large bowl. Add the cheese and season with salt and pepper. Shape the mixture into small oval or round croquettes and transfer to a plate. Cover and refrigerate until firm, 30 minutes.

Spread the breadcrumbs in a shallow bowl. In another shallow bowl, beat the eggs with the mustard and some salt and pepper.

2. Dredge the croquettes in the breadcrumbs, tapping off the excess. Dip in the beaten egg mixture to coat, then dredge again in the breadcrumbs, pressing lightly to help the crumbs adhere.

3. In a large saucepan, heat 1 inch of vegetable oil to 350° F. Working in batches, fry the croquettes, turning, until golden and crisp, about 3 minutes. Transfer to paper towels to drain. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Serves 8

Images: Posters and Potato Ball images courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens and Maite Gomez-Rejon. Potato Possibilities pamphlet from the New York City National Archives.

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, the war already three years in and food was desperately needed to supply America's European allies. American civilians were urged to conserve food by increasing production, cutting waste and consuming foods that were plentifully available. Home cooks began substituting corn, oats or barley for wheat, molasses for sugar, and vegetable shortening for butter or lard. Peanut butter emerged as a protein substitute for meat. Meatless Mondays and Wheatless Wednesdays were encouraged and many Americans had their first vegetarian meal.

President Woodrow Wilson placed food, fuel, iron and steel under government control as war material and, as head of the United States Food Administration, Herbert Hoover sponsored an educational campaign that encouraged American farmers with the slogan, "Food can win the war." Pamphlets, posters and advertisements were produced to teach the rules of substitution and to convince Americans that eating less might improve their health. Canning, drying and preserving foods were skills treated as patriotic duties.

Among the educational pamphlets the United States Food Administration published were Without Wheat, Sweets without Sugar and Potato Possibilities. The latter called the potato "a good food all the time - but especially good war time food for Americans because the use of the potato means the saving of other foods which can be more easily shipped to our own troops and our allies." Potato Balls were among the recipes listed. The following recipe is an adaptation.

Potato Balls

Native to South America, the ready and resilient potato is one of the world's most common foods.

2 pounds baking potatoes, peeled and cut into large chunks

salt and pepper

12 ounces Gruyere, cheddar or mozzarella cheese, cut into 1/3-inch dice

2 cups plain dry breadcrumbs

5 eggs

2 tablespoons Dijon mustard

vegetable oil, for frying

1. In a saucepan, cover the potatoes with cold water. Bring to a boil, salt generously and simmer over medium heat until tender, about 20 minutes. Drain, let cool and mash into a large bowl. Add the cheese and season with salt and pepper. Shape the mixture into small oval or round croquettes and transfer to a plate. Cover and refrigerate until firm, 30 minutes.

Spread the breadcrumbs in a shallow bowl. In another shallow bowl, beat the eggs with the mustard and some salt and pepper.

2. Dredge the croquettes in the breadcrumbs, tapping off the excess. Dip in the beaten egg mixture to coat, then dredge again in the breadcrumbs, pressing lightly to help the crumbs adhere.

3. In a large saucepan, heat 1 inch of vegetable oil to 350° F. Working in batches, fry the croquettes, turning, until golden and crisp, about 3 minutes. Transfer to paper towels to drain. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Serves 8

Images: Posters and Potato Ball images courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens and Maite Gomez-Rejon. Potato Possibilities pamphlet from the New York City National Archives.