Humans have always been fascinated with the heavens. Our distant ancestors understood that Mother Earth was receiving its daylight warmth from the majestic Sun, and its pale, nocturnal light from the Moon. In addition, there were those twinkling point sources of light that the ancients connected by imaginary lines to form mythical constellations. A few "stars" were observed to wander across the sky and they were dubbed "planets" (meaning "wandering stars") by the ancient Greeks.

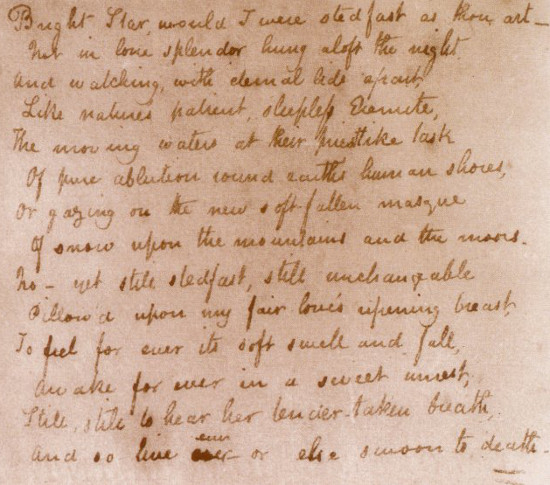

Not surprisingly, the stars have been the subject of many poems. Perhaps none is more romantic than John Keats's "Bright Star." This may have been Keats' last poem before his untimely death in 1821, at age 25. In that poem, which Keats transcribed into a volume of The Poetical Works of William Shakespeare (Figure 1), Keats wished to be as constant as a star:

![2014-08-19-fig1.jpg]()

Figure 1. The poem "Bright Star" by John Keats was transcribed into a volume of The Poetical Works of William Shakespeare. Image in the Public Domain.

The most familiar poem about the stars is probably "The Star" by English poet Jane Taylor (1783–1824). The poem is better known through the sung version of its first line, "Twinkle, twinkle, little star." The music that accompanies the first stanza was taken from an eighteenth century French melody.

Another beautifully romantic poem, "Ah, Moon -- and Star!" by Emily Dickinson, laments the fact that even though the Moon and the star are very far, the poet's beloved is even less reachable. The last, desperate-sounding stanza, reads:

Poems about the stars, and their perceived perfection, are not only common in the western tradition. The great Indian author and poet Rabindranath Tagore (Figure 2 shows him with Albert Einstein), wrote a poem titled "Lost Star," in which he described how one star -- "the glory of all heavens," was thought to have been lost at the time of creation. In the poem, this perception triggered a ceaseless quest to find the "lost" star. The poem concludes, however, by saying that this search is futile, since all the stars (and thereby perfection) are in fact there.

![2014-08-19-fig2.jpg]()

Figure 2. Rabindranath Tagore with Albert Einstein. Photo in the Public Domain.

Even though we know much more about the stars now -- about how they are born, live and die -- our physical existence is so tethered to them, that I am convinced that the stars will continue to inspire magnificent poetry. Astronomy continues to fascinate, and it serves as one of the most powerful magnets, attracting young minds into the sciences. We are stardust after all.

Not surprisingly, the stars have been the subject of many poems. Perhaps none is more romantic than John Keats's "Bright Star." This may have been Keats' last poem before his untimely death in 1821, at age 25. In that poem, which Keats transcribed into a volume of The Poetical Works of William Shakespeare (Figure 1), Keats wished to be as constant as a star:

Bright star, would I were steadfast as thou art --

Not in lone splendor hung aloft the night..."

Figure 1. The poem "Bright Star" by John Keats was transcribed into a volume of The Poetical Works of William Shakespeare. Image in the Public Domain.

The most familiar poem about the stars is probably "The Star" by English poet Jane Taylor (1783–1824). The poem is better known through the sung version of its first line, "Twinkle, twinkle, little star." The music that accompanies the first stanza was taken from an eighteenth century French melody.

Another beautifully romantic poem, "Ah, Moon -- and Star!" by Emily Dickinson, laments the fact that even though the Moon and the star are very far, the poet's beloved is even less reachable. The last, desperate-sounding stanza, reads:

But, Moon, and Star,

Though you're very far --

There is one -- further than you --

He -- is more than a firmament -- from me --

So I can never go!"

Poems about the stars, and their perceived perfection, are not only common in the western tradition. The great Indian author and poet Rabindranath Tagore (Figure 2 shows him with Albert Einstein), wrote a poem titled "Lost Star," in which he described how one star -- "the glory of all heavens," was thought to have been lost at the time of creation. In the poem, this perception triggered a ceaseless quest to find the "lost" star. The poem concludes, however, by saying that this search is futile, since all the stars (and thereby perfection) are in fact there.

Figure 2. Rabindranath Tagore with Albert Einstein. Photo in the Public Domain.

Even though we know much more about the stars now -- about how they are born, live and die -- our physical existence is so tethered to them, that I am convinced that the stars will continue to inspire magnificent poetry. Astronomy continues to fascinate, and it serves as one of the most powerful magnets, attracting young minds into the sciences. We are stardust after all.