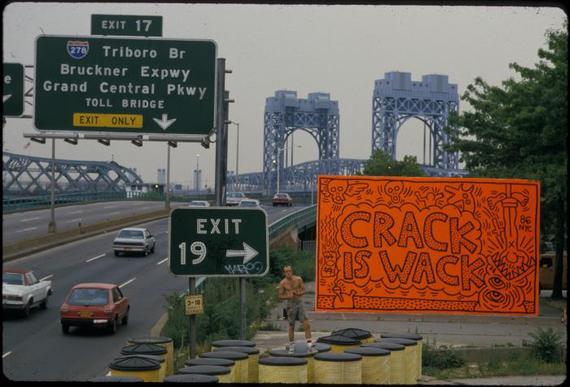

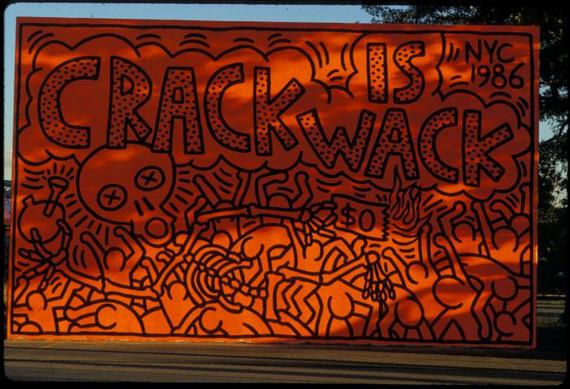

Crack is Wack is arguably Keith Haring's best-known work. It might also be the most famous mural in New York City. For one, it probably has more daily views than any other mural in NYC, due to its location next to passing cars on the Harlem River Drive (in Manhattan at 128th Street).

How Crack is Wack came to be is not well-known. Nor is the fact that the mural is not the original version.

Benny was one of the major catalysts for Crack is Wack. Benny was Haring's young, gifted studio assistant in the mid-1980s who became addicted to crack. Haring and the rest of his studio were close with him and they tried everything to help him kick his addiction. This was, according to Haring, an incredibly distressing experience for everyone involved. Benny had no health insurance, so they initially called cocaine hotlines and Benny started to see a counselor, but that didn't work. Haring's studio also went to emergency rooms to try to get him into a guided program, but no hospital would take him.

Around this time, Haring often drove past a handball court located in a small park near the Harlem River Drive. The court was clearly visible from the highway but abandoned. Nothing fenced in the court and no one played on it (because if you did, the ball would just go onto the highway). According to Haring, the location seemed a perfect spot to paint. It was almost identical to a highway billboard.

The subject for the painting quickly became crack. (In Haring's words, "Inspired by Benny [who was eventually cured], and appalled by what was happening in the country, but especially New York, and seeing the slow reaction (as usual) of the government to respond, I decided I had to do an anti-crack painting.")

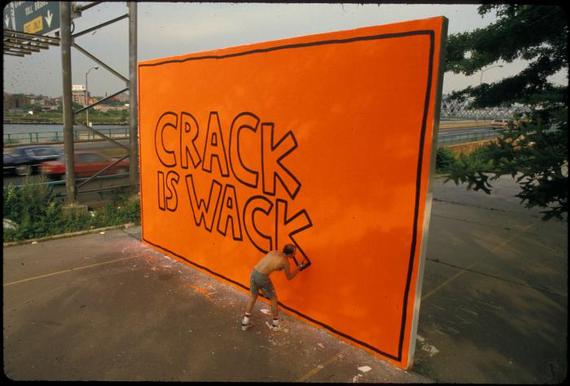

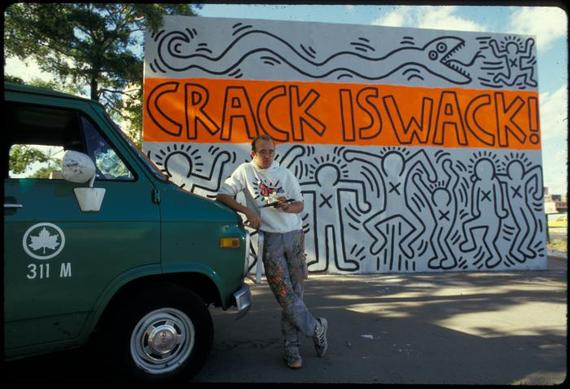

Haring painted Crack is Wack without asking for permission. One morning, during the summer of 1986, he drove a rented van -- loaded with some ladders from his studio and some new fluorescent orange paint he had bought -- up to Harlem to paint.

He finished the entire mural in one day.

While a lot of people came to watch and cars honked their horns from the road in appreciation, no one bothered Haring and his group -- not even policemen. According to Haring, "When you have a van, ladders, and paint, policemen don't even consider asking whether you have any permission, they just assume you do."

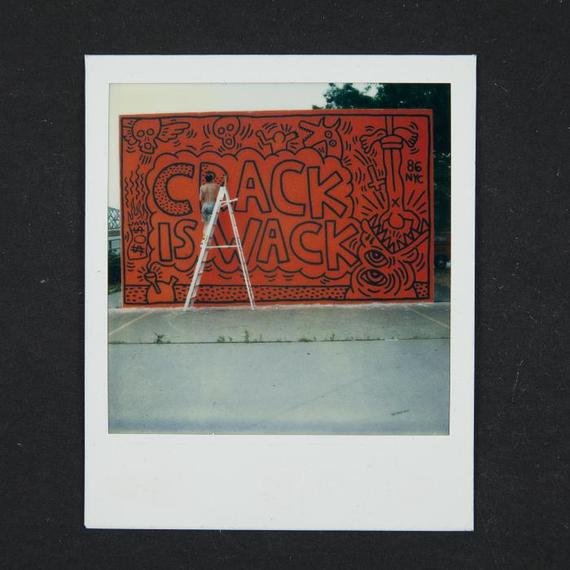

This peace was short-lived. As Haring and his crew were taking some last-minute pictures and smoking a joint, a cop car drove up and one of the policemen started harassing them. The cop asked if Haring had permission to create the mural, and obviously he didn't. Haring was then arrested and handed a court date. He faced a fine and potentially jail time.

In the next days and weeks, the mural was quickly picked up by the news media, not because of Haring's arrest -- no one knew he had been arrested -- but because of the newsworthiness of crack cocaine and Reagan's "War on Drugs" then in the United States. Haring explained: "Every time the news did a story on crack, they would flash to the [mural as a visual]. NBC [even] did a public service announcement using it as a background."

Close to the court date, the New York Post contacted Haring and asked if they could take a picture of him in front of the mural. In the process of taking it, they learned about Haring's arrest and were shocked. They had no idea he was going to soon be in court and had been arrested for making the mural. The next day the Post ran an article about Haring and the mural with the information that he could go to jail for a year.

People immediately came to Haring's defense. The topic even made the evening news, which prompted Mayor Edward Koch -- who was both anti-crack and anti-graffiti -- to have to consider the issue. Koch commented that "we have to find somewhere else for Haring to paint."

Haring eventually was fined only $100. After the court date, the Parks Commissioner wrote to Haring to apologize to him and offer any help he could provide, since the mural was actually Parks Department property, not city property.

Roughly a week later the mural was vandalized. Someone in the neighborhood turned it into a pro-crack mural. And then, according to Haring, to deal with this, some "busy bee in the Parks Department" took it upon themselves to paint over the entire mural in gray without consulting his supervisors. So Crack is Wack was then gone.

Upon learning that the work had been painted-over, the Parks Department commissioner called Haring and apologized (again). He then asked if Haring would consider repainting the piece with his department's assistance.

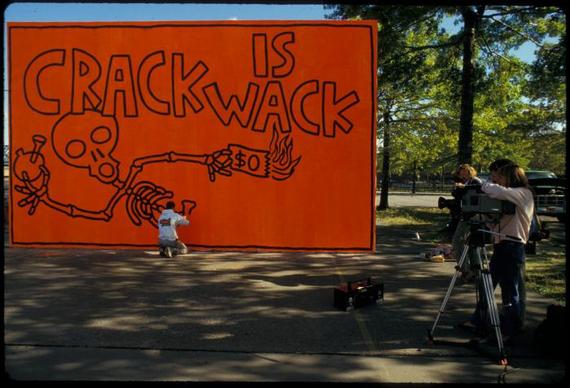

Haring then repainted Crack is Wack -- though differently than the original version.

Crack is Wack has remained pretty much untouched since, though it underwent a 2007 renovation.

Several years after Haring's untimely death in 1990 at age 31 from AIDS-related illnesses, the park was officially named the "Crack Is Wack Playground."

Credit for all photographs except for #3 (the polaroid image): Crack is Wack, 1986 © Keith Haring Foundation Photo by Tseng Kwong Chi © 1986 Muna Tseng Dance Projects, Inc., New York. Polaroid image is © Keith Haring Foundation.

This is the third in a series of posts on individual artworks. Previous posts have concerned one of Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills and Jean-Michel Basquiat's Pegasus, 1987.