There is a well-known story about the painter Richard Diebenkorn that goes like this: One day in the early 1950s, when Diebenkorn was living and teaching in New Mexico, someone commented to him that he probably wasn't very good at realism. Stung into action, Diebenkorn tossed off a convincing portrait sketch of a nearby man and more than made his point: that he wasn't an abstract painter simply because he was incapable of traditional rendering. Diebenkorn was a complete painter, and he wasn't about to be let someone's assumptions about his limitations go unchallenged.

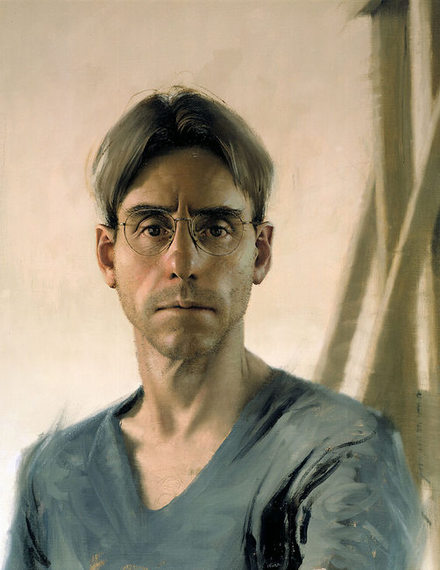

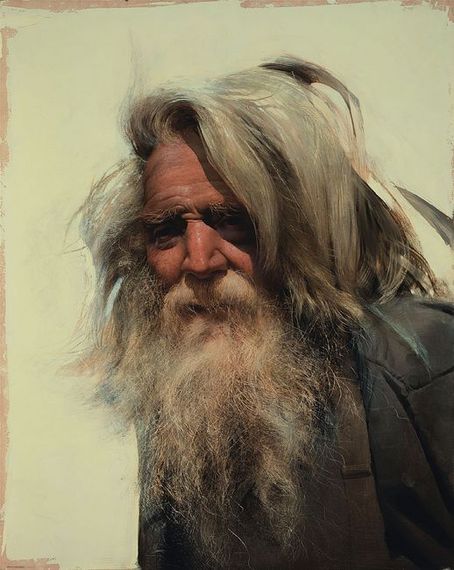

Daniel Sprick, whose work is now on view at the Denver Art Museum, has been creating paintings for more than a decade that make a similar point, but in reverse. Any assumptions you make about his limits are very likely going to be wrong too. Sprick is an almost absurdly talented realist who it would be easy to label as a "tight" painter: he can lasso paint into perfectly limned contours and burnish human features into glowing, baby-bottom smoothness. Sprick can also let the paint run free and tell him what to do: underneath his realism he leaves patches of vivid, freely brushed abstraction. He also paints the wildness of hair with anarchic verve.

Daniel Sprick, Tom T., Oil on board, 16 x 20 inches

Who is this guy who can handle the brush like Joan Mitchell -- or a Chinese literati painter -- in the morning, and then morph into Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres by dinner? This may not sound like a compliment, but Sprick's technique is so varied that it is almost schizophrenic.

Sprick is many painters in one, and there is something conceptual about his approach. The conceptual element is there in the fact that each painting displays what the artist Vincent Desiderio calls a "narrative of creation." In other words, Sprick's paintings are utterly clear about how they are made: when seen as a whole they represent -- among other things -- a rebuke to photo-realism, which looks tame compared to what he does. Looking over a Sprick painting is an experience in being both "wowed" by his sheer bravura skill while also appreciating the artist's ability to balance his intellect with his intuition. Sprick paints hard and feels deeply.

As if Sprick didn't have enough to offer just in terms of virtuosity, there is another element to his portraits that has to be praised. You might expect that someone with his self-confidence could be detached from his subjects: far from it. Sprick has the knack for seeing people's inner vitality -- maybe it is related to his knack for understanding abstract energies -- and even when his portraits achieve refinement his subjects never lose their mojo. Take a look at the people that Dan Sprick paints and you will notice that however varied they are on the surface they all have one thing in common in emotional terms: they are all wide open to being painted by Daniel Sprick. They love being part of his oeuvre even though much of his work isn't flattering in conventional terms and there is at least a hint of affectionate caricature in his strongest works.

Honestly, who wouldn't want Sprick to paint their portrait? The man is a living master. Like Diebenkorn he is more than up to the challenge of surprising you with his versatility.

John Seed in Conversation with Daniel Sprick

Dan, tell me about why you chose "Fictions" as the title for your show in Denver.

If you see yourself showing up in a short story, you may recognize parts of yourself that are drawn accurately, parts that are grafted from another model, and other parts from vapor and dusk. these narratives may be vague, but they are fictions, which was observed by Timothy Standring, who chose the title.

When we paint, we internalize and filter all the raw data of existence through our sensibilities, experiences, abilities and shortcomings. We also mix in our habits, biases, preconceptions and aesthetic preferences. Then we stir it up with our natural emotional responses, and out comes -- lord knows what -- a variation on the initial experience. The end result is a kind of a daydreaming other world: a fictional world.

Daniel Sprick, Ketsia in Profile, Oil on canvas on board, 22 x 28 inches

Is it fair to say that your work combines a variety of ideas and approaches? I see realism, abstraction and also conceptualism.

There was an article in which you discussed that there are various art worlds with little overlap or awareness of each other: parallel universes without contact. But I keep hearing the term ''bridge'' between traditional academic work and contemporary art as applied to this show. Christoph Heinrich, the director of the Denver Art Museum, has a background as curator of modern and contemporary in Germany, yet he shows genuine enthusiasm about this work and indicates that it dovetails with his goals. I am humbled by this, and very, very grateful.

How do you hope people will react to your work when they see it?

Curator Timothy Standring, who worked directly with me in Denver, said to a group after the reception that it is rare to have an opening in which people are actually looking at the paintings more than at each other. I heard reports of viewers moist in the eyes, and I noticed a bit of that myself. To connect on an emotional level is the most that an artist can hope for.

Conversely, it will always be a big ol' world with many valid points of view, and none of us can expect 100 percent acceptance. I am presently reeling from the most carefully thought out, intelligently written, long, bitter and vitriolic attack I've seen against any one since elementary schoolyard days. Though it stings, I am flattered by the amount of effort he put into it. So thank you, mister.

How can a skilled artist practicing realism today endow his/her work with a sense of contemporaneity?

An artist can internalize contemporary sensibilities, not so much by staying up to date on trends at Art Basel Miami, but by being true to him/herself and by indulging in the realm of the senses: observing and feeling, being influenced more by life itself than by the art world.

How do the different elements in your work compliment each other?

For years I've heard that the term ''de-skilling'' is being used in university art schools, apparently meaning that craft is believed to be an impediment to expression, and for sure: technical perfection as an end in itself can be lifeless. At the opposite end of the scale, if I am wildly expressive and full of emotion, in a language that no one recognizes, I am a man babbling in tongues out on the street. Then there is the art of no feeling and no craft either: supported by verbose and incomprehensible theories to keep investors buying into it.

Emotional expression can flourish when combined with highly practiced traditional academic skill. My taste leans toward understatement and subtlety. The works are not exactly accurate: they are embedded with errors due to my basic human shortcomings and also due to intentional exaggerations or caricature.

In the careful realism of my pieces there is also something in there that is a little bit wrong, but it may convey some interesting other world.

How do you see your work as fitting into the long lineage of postwar figuration?

Nathan Oliveira conveyed an otherworldliness and expressed powerful emotion with recognizable figures during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism: his work constituted a bridge. Lucien Freud is another bridge artist between worlds; so is F. Scott Hess. There is a sequence, a progression from 1950's to today. I think that what I am doing follows in that sequence.

It is possible to carefully craft artwork in the long tradition of realism while being expressive and relevant to our times. Realism was certainly not exhausted at the end of the nineteenth century.

All images ©Daniel Sprick

Daniel Sprick Portrait from APAIRUS COMPANY on Vimeo.

Daniel Sprick's Fictions: Recent Works

The Denver Art Museum

June 22, 2014 - November 2, 2014

Hamilton Building