The sensible Joe Nocera is concerned: Apple has lost its creative mojo. Instead of trying to put new dents in the universe, Apple is involved in never-ending litigation, squabbling with competitors over patents. Even worse, Apple "has become risk-averse, its innovative capacity reduced to making small tweaks on products it has already brought to market." In search of an explanation, Nocera descends to quoting B-school jargon, about critical mass and innovators' dilemmas. But in fact you don't need an MBA to know which way this wind is blowing. You just need to know about Picasso and Dylan.

Years ago, Malcolm Gladwell said in a speech that Apple was Picasso, and Dell was Cézanne. At the time, all Gladwell meant was that Apple innovated conceptually, and Dell experimentally. But I believe Gladwell was even more right than he understood.

Picasso wasn't merely a great conceptual innovator, who made a dramatic innovation and spent the rest of his life basking in the wealth and fame it brought. Picasso was more ambitious than that: he wanted to be not only the greatest artist of his time, but of all time, and he understood that that required multiple innovations. He also understood that the way to do that was to make a great innovation (Cubism), and then to do Something Completely Different (collage), and then to do Something Else Completely Different (stylistic versatility).

|

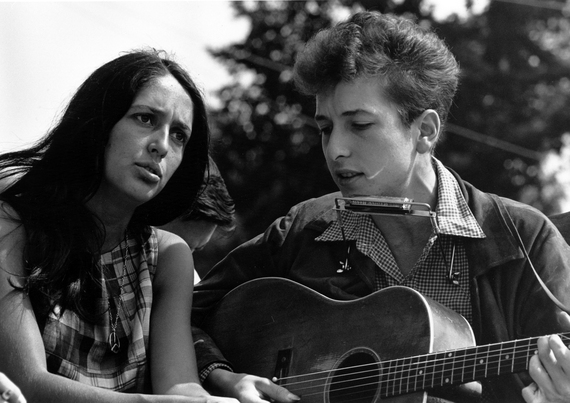

Picasso was the prototype of the versatile conceptual innovator, and among those who followed him in this behavior was Bob Dylan. In Chronicles, Volume 1, Dylan recalled being a young folksinger in Greenwich Village, and reading about the aged Picasso, still kicking in his 80s, not content to sit on the sidelines, and thinking: "Picasso had fractured the art world and cracked it open. He was revolutionary. I wanted to be like that." Dylan went on to become the most protean of popular musicians, going through "so many transformations, emotionally and musically and even physically," that admirers like Joyce Carol Oates believed that "he must be a fictional character."

|

Steve Jobs considered Dylan "one of my all-time heroes." He quoted "The Times They Are a-Changin'" at the unveiling of the Macintosh, and played "Like a Rolling Stone" at the launches of both the iPhone and the iPad. But Jobs didn't just love Dylan's music. He understood, and admired, Dylan's behavior: "I learned the lyrics to all his songs and watched him never stand still. If you look at the artists, if they are really good, it always occurs to them at some point that they can do this one thing for the rest of their lives, and they can be really successful to the outside world but not really successful to themselves." But there would come a key moment, when "an artist really decides who he or she is. If they keep on risking failure, they're still artists. Dylan and Picasso were always risking failure."

And so was Jobs. He didn't care about being the richest entrepreneur in Silicon Valley, so he wasn't content simply to make the Apple II.2, or the Apple III. He wanted to be the greatest entrepreneur ever, and he knew that to do that "you have to not look back too much. You have to be willing to take whatever you've done and whoever you were and throw them away." And Now for Something Completely Different: iPod, iPhone, iPad.

|

But Steve Jobs died, and it's hard to believe he really thought Tim Cook would be a great innovator as his successor as CEO of Apple. More likely, Jobs chose Cook because he knew that Cook would make Jobs look even greater in retrospect. In Yukari Kane's book, Haunted Empire, she variously describes Cook as calm, rational, organized, prepared, realistic - all in direct contrast to Jobs.

One of the funniest sentences in Kane's book is: "Like Jobs, Cook claimed to be a Dylan fan." Tim Cook may or may not really like Bob Dylan's music, but there is little doubt that he has no real understanding of Dylan's protean behavior in pursuit of greatness: unlike Jobs, who was a gambler, willing to risk his reputation and his fortune on a new, insanely great product that could send a giant ripple through the universe, Cook is just another boring MBA who loves to read spreadsheets to try to cut costs. Walter Isaacson wrote that Steve Jobs' favorite words were "revolutionary" and "incredible;" it seems unlikely that Tim Cook uses these with any frequency. And because of that, Apple is no longer Picasso, or Dylan, or Jobs.