This is the year of Judy Chicago.

In honor of her 75th birthday this July, the iconic feminist artist is hosting what she calls a "dispersed retrospective," scattering her life's work -- five decades of art making -- across a selection of museums and galleries from California to New York. In 2014 alone, she'll be featured in the Brooklyn Museum, MANA Contemporary, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Schlesinger Library, the Palmer Museum of Art, the Oakland Museum of California, the New Mexico Museum of Art and Denver's RedLine. She's also releasing two major tomes, "Institutional Time" and the aptly titled "The Dinner Party: Restoring Women to History."

"I’m not going to retire!" Chicago declared in an interview with The Huffington Post, pointing out what only seemed obvious. "Artists don’t retire. Every artist’s dream is to drop dead while they’re working."

![birth hood]()

Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Birth Hood, 1965/2011. Sprayed automotive lacquer on car hood, 42 7/8 x 42 7/8 x 4 5/16 in. (109 x 109 x 10.9 cm). Collection of the artist. © Judy Chicago. Photo © Donald Woodman.

The cross-country celebration of all things Chicago will cover her early years as a painter and sculptor in Southern California to her pivotal role as the founder of the feminist art programs at California State University in Fresno and the California Institute of the Arts (when she changed her name to Judy Chicago "to liberate herself from male-dominated stereotypes") to the decades she spent creating multimedia works in New Mexico. It's a vast time period that includes the unforgettable "Womanhouse," "The Dinner Party," "Through the Flower," and "Birth Project," all of which led up to her involvement in 2011's "Pacific Standard Time," the Getty museum's homage to the birth of Los Angeles art. Chicago, rightly so, landed herself a place in the canon, cementing her status as a woman artist to be reckoned with.

As both an artist and an educator, who returned to the world of academia in the late 1990s, Chicago has always held the discipline of art history close to her heart. She grew up unaware of the historically powerful women who came before her, a lack of knowledge she more than made up for with her massive ceremonial tribute to the female figures who've pushed cultural boundaries for centuries. Now housed at the Brooklyn Museum, "The Dinner Party" is but one aspect of a lifetime devoted to the philosophy of feminism and carving out a curriculum that corrects for eons of male-centric narratives.

"Feminism, the belief that everyone is entitled to a life of dignity, has evolved over several centuries and brought women in the Western world unprecedented opportunities," she writes in "Institutional Time." "This historical struggle for freedom deserves to be both honored and taught -- to everyone."

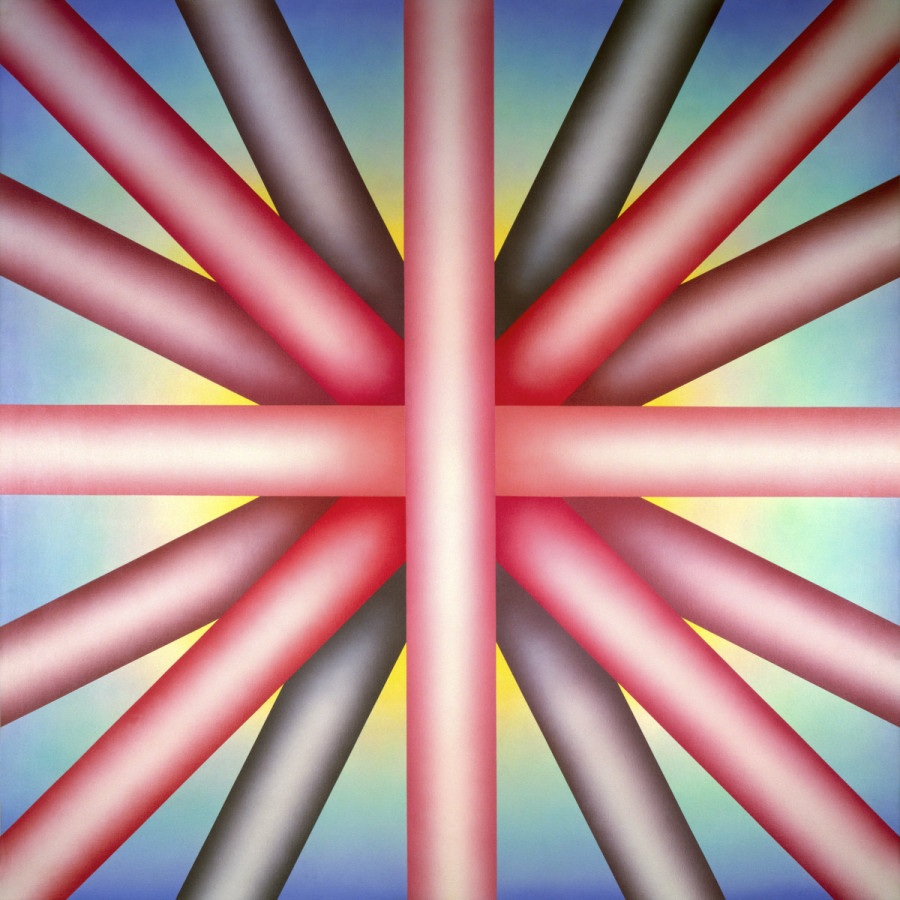

![heaven]()

Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Heaven is for White Men Only, 1973. Sprayed acrylic on canvas, 80 x 80 in. (203.2 x 203.2 cm). New Orleans Art Museum, Gift of the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, 93.12. © Judy Chicago. Photo: © Donald Woodman.

We spoke to Chicago this past January as she prepared for her 2014 calendar. From the conference room of her New York City hotel, she relayed her concerns about inter-generational knowledge, the power of institutional change and her advice for emerging artists. Here's a taste of where an hour speaking with Judy Chicago can take you:

As a historian and an artist, where do you see the conversation between generations of feminists happening?

It's funny that you ask that. I've spent some time with a young woman artist whose name is Audrey Chan. I first met and encountered Audrey -- she’s a performance artist -- when she appeared on a panel about feminist art dressed as me. And I really didn’t understand her motivation until we spent this time together. I heard about her from a former student of mine, Suzanne Lacy, the activist artist. Then I heard that Audrey was teaching at The Getty when "Pacific Standard Time" was there and that she was touring "Pacific Standard Time" and talking about my work dressed as me. I immediately noticed that she sort of had my ‘70s look. I thought she could use some updating. So I offered to take her shopping, to update her look. So we went shopping. She took me to TJ Maxx. I bought her some earrings. And we found a great top for her and that was that.

A couple of months later she got in touch with me and said she had approached a publisher about doing a book based on the intergenerational dialogue that we had spontaneously generated when we started talking. I didn’t even realize it had that big of an impact on her. So when she was in New Mexico -- she came out to have another step in the conversation, for which she had dressed as me in the updated look -- she was telling me that she went to CalArts for her MFA. CalArts, as you know, is one of the premiere art schools in the country. And she said that she felt completely… she did not feel mentored at CalArts. She felt like she wanted a role model. She told me something that I didn’t know: that even though I don’t live in L.A. anymore, particularly for the younger women artists, I’m a big presence. Even though I wasn’t physically there. I didn’t know this, because for a long time the art world tried to pretend that I hadn’t had any influence. And so because I wasn’t there, she wanted to create me. To have me be there.

So that’s what first motivated her to start dressing as me. Once that got her access to me, then she really wanted to cross generations. She does this piece, this performance piece called “How I Became a Feminist Artist Even Though I Didn’t Live Through the ‘70s.” One of the things we talked about, is that even though CalArts is the site of where I brought the Fresno Feminist Art Program and CalArts is the program that did "Woman House," CalArts had subsequently completely erased the feminist art program from its institutional memory.

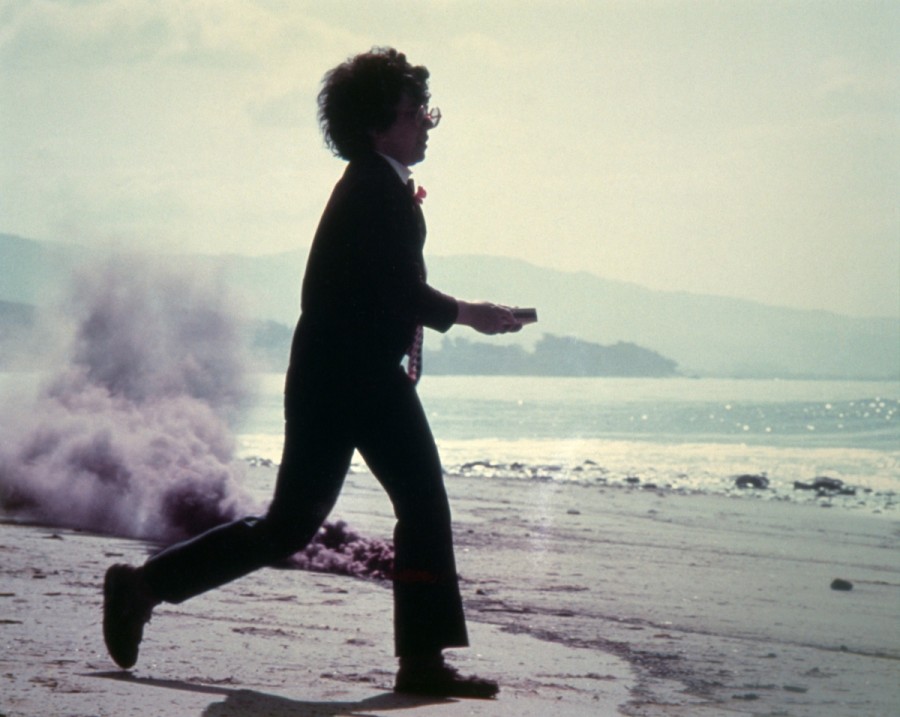

![dry ice]()

Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Dry Ice Environment Documentation, 1967. Photos courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

Why was that?

You’d have to ask them. But there were some women students in the ‘90s who discovered that there had been feminist art there. All these women found was one box in the archives [of the school], from the whole feminist art program at CalArts. What this means is that the art institutions and museums are not transmitting either the history of the feminist art movement or enough women’s history. It has not been integrated into the curriculum and therefore young women are not able to build on what women have done before them.

It’s exactly what happened when I was your age. I didn’t know about the women and women artists before me and so I could not build on their insights or their art -- the cultural production of my predecessors -- until I did my own research. So now how disheartening is it to see that these young women are having to do the same thing? Even after 40 years.

So if this transmission of history is not happening in institutions and not happening in museums, what's the next step?

Well, there has to be a complete transmission of thinking. When women were first integrated into higher education in the 19th century, there was absolutely no thought to the fact that they were being brought into an entirely male-centric curriculum. And with very few exceptions, there has been no effort to change that. There have been efforts to add on a few women, in the cases of women in color, for instance, but there’s been no effort to explain that what we’ve been transmitting is a narrow history. A narrow, phallocentric history. And a Western one, too. Now that we’re moving into such a globalized world, how arrogant is it to teach Western history as if it is world history? As if it is universal history? How arrogant is it to show [imbalanced proportions of] white male art at the National Gallery in Washington, DC, which is a tax-funded institution? Its statistics are appalling. Really skewed. Is that the history of America? Is that the history we want young people to learn?

But that is a highly contested set of issues. Because how history is written, both in and out of art institutions, is how you shape the world. And so giving up control of that and rethinking that hasn’t happened. It’s not enough to have a few women’s studies courses. Why is it more important to study Paul Revere’s midnight ride than it is Susan B. Anthony’s 50-year effort to transform the face of America for women? How off balance is that? Men really cannot conceive of what it’s like to grow up and look on television and see that all the major sports figures are male, all the major politicians are male. If you go to an art institution, most of the art is by men. When you’re in school, most of the events you study are about men. Men’s activities lauded and repeated over and over. What about us? What about commemorating the decades-long struggle for suffrage? Why don’t we hear those stories over and over and over again. It’s almost inconceivable for men to understand what it would be like to live without that constant valorization.

One of the reasons I think people said seeing “The Dinner Party” changed their lives is because it reminded them of the complete absence that they had grown up with, that they had never even noticed until they had presence.

![rainbow]()

Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Rainbow Pickett, 1964. Latex paint on canvas-covered plywood, 126 x 126 x 110 in. (320 x 320 x 279.4 cm). Collection of David and Dianne Waldman, Rancho Mirage, CA. © Judy Chicago, Photo © Donald Woodman.

I think this hits on an important point. It becomes a conversation when we are adults, but when you grow up as a girl, going to a museum and seeing nudes and masculine imagery and not understanding the context of these images. We can talk about how much digital media is changing the conversation, but how do we change the conversation for a 10-year-old girl or child of color?

That’s absolutely right.

You write about this at the beginning of “The Dinner Party: Restoring Women to History,” that you encountered professors in your early studies who simply believed women had not contributed to history. Do you still encounter individuals like that?

It’s hard to believe, right? Well, a few years ago when I showed at a gallery in Santa Fe, around the time of the permanent housing of “The Dinner Party,” my gallerist flat out told me that he had been at a party and this man said -- in response to a viewing of my Hatshepsut plate, one of the four female pharaohs -- that there have never been any female pharaohs. Yes, there’s still a built in resistance because that’s what people grow up learning. They grow up learning it. And like you were saying, about not having that, how can we become empowered and claim space in the world and feel confident while feeling bereft?

I’m noticing more and more that institutions -- like MoMA and its “Designing Modern Women” exhibition -- are looking into their permanent collections and trying to find those women artists to create exhibitions that reframe history, however efficiently they end up doing that.

Let’s look at MoMA. I read the “Designing Modern Women” catalogue and I went to the show and when I walked in saw [signs for] Matisse, Monet, etc. All men. And then there was a small sign for “Designing Modern Women.” One of the things happening in major institutions like that, which are the pillars of the phallocentric narrative in art, is that they are trying to figure out how to include more women and artists of color without disturbing the existing narrative. It’s not an accident that my work is not in any of those major collections because my work would disturb those narratives.

I heard a story told to me by [a curator]. He said that whenever he brought up acquiring a woman artist, the first question was: How big is the work? And if the work was too big they wouldn’t take it. They’d only take it if it was small.

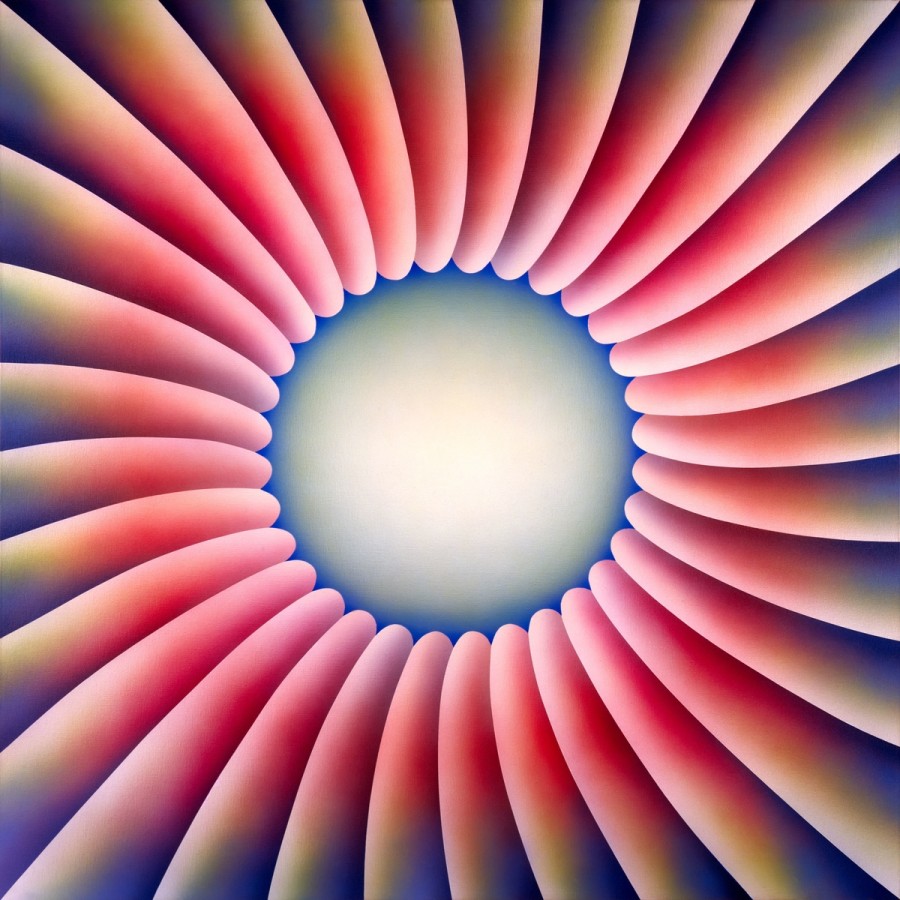

![ttf]()

Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Through the Flower, 1973. Sprayed acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 in. (152.4 x 152.4 cm).Collection of Dr. Elizabeth A. Sackler, New York, NY. © Judy Chicago. Photo © Donald Woodman.

Why do you think that is?

So that it could remain minor. So you have a small Hannah Wilke and a small Louise Bourgeois. At MANA this year, the show is going to have my 32-foot-long painting and a 22-foot-long drawing. Two of my large scale works from my early career. And that is why I’m having a spread out retrospective, as opposed to one major institution. Because there is not one institution in the world that would accord 92,000 square feet to a woman artist like what was accorded to Jim Turrell last year.

There were a lot of criticisms charged against “Designing Modern Women’s” organization and the curatorial emphasis on women who collaborated with powerful men. Which reminds me of Ken Johnson’s interpretation of the exhibition. He attempted to point out that women might be naturally prone to collaboration. Which seems ridiculous. Perhaps women aren’t naturally prone to collaboration, but some women, over the years, have realized that working in groups -- composed of both men and women -- can be advantageous to one’s career.

Yes, that’s good insight.

It’s sort of remarkable, that rhetoric that persists, that all women are naturally anything.

How do we even know what we naturally are? We’ve never hardly ever had the opportunity to demonstrate it in public space, with enough of us to make a difference.

Right. Do you feel that you are part of any one community of feminist artists or feminist academics or women artists?

I was very instrumental in creating the women’s community in L.A. in the ‘70s, but a lot of things happened since then. First of all, I left the women’s workshop there, I stopped teaching because I had such a burning desire to make art. But also, as I matured, I began to understand that we had cast the dialogue incorrectly in the ‘70s, in terms of it being strictly around gender. As it played out, it turned out that not all women were our friends and not all men were our enemies. What I began to understand is that it had more to do with values.

In “Institutional Time,” I have a chapter called “What About Men?” When I went back to teaching in 1999 it was one of my goals to find out if my pedagogical methods could apply to men as well as women. And when I was working on that chapter, I went and did research on men’s participation in the feminist movement. I was completely blown away discovering that there had always been men. There were 20-30 men at the Seneca Falls Conference in 1848. I didn’t know that! There were men’s auxiliaries to the suffrage movement that marched with the women side-by-side. That history has been erased. Frederick Douglas was an ardent supporter of women, but if you read his biographies it’s hardly mentioned. If you’ve ever read anything by Emily Dickinson and the man who championed her -- Thomas Wentworth Higginson -- he was a huge supporter of women’s suffrage, and he’s never mentioned. So that history has been erased, because it’s not in the interest of male dominance to discuss the men who have stood up against phallocentric culture, who have tried to support women’s equity. So men who feel stranded feel stranded like we do, without role models.

![silver blue]()

Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Silver Blue Fan from Fresno Fan series, 1971. Sprayed acrylic on sheet acrylic, 60 x 120 in. (152.4 x 304.8 cm). Collection of Glenn Schaeffer, New Zealand. © Judy Chicago. Photo © Donald Woodman.

You’ve discussed this before, that your art isn’t necessarily political art but that it’s about morals.

Morals, yes. I have a passion for justice, which was instilled in me by my father. Justice for everyone, including non-human creatures.

Which is the direction that intersectional feminism is headed in today. Justice for all. If you could give your own pocket definition of feminism to someone in conversation, what would it be. Do you have a short answer?

Yes, it would be like bell hooks. Feminism is for everybody. That’s my pocket definition! Especially for everybody who believes in the idea that every creature, human and nonhuman, has a right to live out their own lives with dignity. You know, when people say to me that we live in a post-feminist world, I wonder what world they live in. Do you live in a tiny little world of middle class America? Yeah, maybe.

There are many people who identify as “non-feminists,” who want to define it or minimize its importance. People, who don’t attempt to understand the feminist philosophy, but who can really dominate the public conversation.

It’s unbelievable. It really is. How they can dominate and manipulate the conversation.

So where’s the megaphone for feminists to shout back at them?

Well, just putting women in power isn’t sufficient. Because there are a lot of women who are not friends of women. Who are not changing the narrative, they are maintaining it, because their power depends on supporting the narrative.

That’s where statistics fail us. When people with a voice focus on the numbers of women in power, and feel as though something has been accomplished when those numbers reach 55%, without breaking down the meaning of those numbers. Out of curiosity, do you come across these types of statistical comparisons in the art education world?

In art school, even though female students outnumber males, still, in terms of tenured faculty, white males are still the norm.

![purple]()

Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Purple Atmosphere #4 Documentation, 1969. Photo courtesy Through the Flower Archives.

My last question, which I asked you two years ago, but now that it's your 75th birthday, I'd like to ask again: What advice do you have for young artists today?

It's a real challenge now to be a real artist. First of all, the graduate schools are pumping out hundreds of thousands of artists into a tiny distribution system. Meanwhile, most of these young people, if they don't come from money, have had to take out a huge amount of student loans so they're burdened by debt. So now my advice to young artists is: Stay out of the market place. Get a job so that you can support yourself and make art when you can. At night, on the weekends, on vacation and focus on finding your own voice and forging your own vision. And only then enter the marketplace, when you're on solid ground. Because the marketplace is chewing up and spitting out young artists like detritus.

For young women, learn your history and the history of feminist art. Because so many young artists are reinventing the wheel. I see so many young women making art that came out of "Womanhouse" in the '70s. A lot of the content is the same because a lot of the issues are the same -- sexual identity, freedom, independence. When I went back to teaching I saw these women who had been told they could "have it all" and they live in a post-feminist world, and they were struggling with that. There was this performance at Indiana University with these two women -- one dressed as a clown and the other sitting on stage. The one dressed as a clown is putting balloons in the other woman's lap, one by one. One represents college. One represents friendships. Then comes another one. Relationships. Career. Marriage. Ok, now she's juggling all these balloons when the clown comes out and drops the baby. Now she's got all these balloons and she simply can't balance all six of them. She can't. Women still struggle with this concept of "having it all." It's not a post-feminist world.

All images are courtesy of "Chicago in L.A.: Judy Chicago's Early Work, 1963–74" which will be on view at the Brooklyn Museum from April 4 to September 28, 2014.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

In honor of her 75th birthday this July, the iconic feminist artist is hosting what she calls a "dispersed retrospective," scattering her life's work -- five decades of art making -- across a selection of museums and galleries from California to New York. In 2014 alone, she'll be featured in the Brooklyn Museum, MANA Contemporary, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Schlesinger Library, the Palmer Museum of Art, the Oakland Museum of California, the New Mexico Museum of Art and Denver's RedLine. She's also releasing two major tomes, "Institutional Time" and the aptly titled "The Dinner Party: Restoring Women to History."

"I’m not going to retire!" Chicago declared in an interview with The Huffington Post, pointing out what only seemed obvious. "Artists don’t retire. Every artist’s dream is to drop dead while they’re working."

The cross-country celebration of all things Chicago will cover her early years as a painter and sculptor in Southern California to her pivotal role as the founder of the feminist art programs at California State University in Fresno and the California Institute of the Arts (when she changed her name to Judy Chicago "to liberate herself from male-dominated stereotypes") to the decades she spent creating multimedia works in New Mexico. It's a vast time period that includes the unforgettable "Womanhouse," "The Dinner Party," "Through the Flower," and "Birth Project," all of which led up to her involvement in 2011's "Pacific Standard Time," the Getty museum's homage to the birth of Los Angeles art. Chicago, rightly so, landed herself a place in the canon, cementing her status as a woman artist to be reckoned with.

As both an artist and an educator, who returned to the world of academia in the late 1990s, Chicago has always held the discipline of art history close to her heart. She grew up unaware of the historically powerful women who came before her, a lack of knowledge she more than made up for with her massive ceremonial tribute to the female figures who've pushed cultural boundaries for centuries. Now housed at the Brooklyn Museum, "The Dinner Party" is but one aspect of a lifetime devoted to the philosophy of feminism and carving out a curriculum that corrects for eons of male-centric narratives.

"Feminism, the belief that everyone is entitled to a life of dignity, has evolved over several centuries and brought women in the Western world unprecedented opportunities," she writes in "Institutional Time." "This historical struggle for freedom deserves to be both honored and taught -- to everyone."

We spoke to Chicago this past January as she prepared for her 2014 calendar. From the conference room of her New York City hotel, she relayed her concerns about inter-generational knowledge, the power of institutional change and her advice for emerging artists. Here's a taste of where an hour speaking with Judy Chicago can take you:

As a historian and an artist, where do you see the conversation between generations of feminists happening?

It's funny that you ask that. I've spent some time with a young woman artist whose name is Audrey Chan. I first met and encountered Audrey -- she’s a performance artist -- when she appeared on a panel about feminist art dressed as me. And I really didn’t understand her motivation until we spent this time together. I heard about her from a former student of mine, Suzanne Lacy, the activist artist. Then I heard that Audrey was teaching at The Getty when "Pacific Standard Time" was there and that she was touring "Pacific Standard Time" and talking about my work dressed as me. I immediately noticed that she sort of had my ‘70s look. I thought she could use some updating. So I offered to take her shopping, to update her look. So we went shopping. She took me to TJ Maxx. I bought her some earrings. And we found a great top for her and that was that.

A couple of months later she got in touch with me and said she had approached a publisher about doing a book based on the intergenerational dialogue that we had spontaneously generated when we started talking. I didn’t even realize it had that big of an impact on her. So when she was in New Mexico -- she came out to have another step in the conversation, for which she had dressed as me in the updated look -- she was telling me that she went to CalArts for her MFA. CalArts, as you know, is one of the premiere art schools in the country. And she said that she felt completely… she did not feel mentored at CalArts. She felt like she wanted a role model. She told me something that I didn’t know: that even though I don’t live in L.A. anymore, particularly for the younger women artists, I’m a big presence. Even though I wasn’t physically there. I didn’t know this, because for a long time the art world tried to pretend that I hadn’t had any influence. And so because I wasn’t there, she wanted to create me. To have me be there.

So that’s what first motivated her to start dressing as me. Once that got her access to me, then she really wanted to cross generations. She does this piece, this performance piece called “How I Became a Feminist Artist Even Though I Didn’t Live Through the ‘70s.” One of the things we talked about, is that even though CalArts is the site of where I brought the Fresno Feminist Art Program and CalArts is the program that did "Woman House," CalArts had subsequently completely erased the feminist art program from its institutional memory.

Why was that?

You’d have to ask them. But there were some women students in the ‘90s who discovered that there had been feminist art there. All these women found was one box in the archives [of the school], from the whole feminist art program at CalArts. What this means is that the art institutions and museums are not transmitting either the history of the feminist art movement or enough women’s history. It has not been integrated into the curriculum and therefore young women are not able to build on what women have done before them.

It’s exactly what happened when I was your age. I didn’t know about the women and women artists before me and so I could not build on their insights or their art -- the cultural production of my predecessors -- until I did my own research. So now how disheartening is it to see that these young women are having to do the same thing? Even after 40 years.

So if this transmission of history is not happening in institutions and not happening in museums, what's the next step?

Well, there has to be a complete transmission of thinking. When women were first integrated into higher education in the 19th century, there was absolutely no thought to the fact that they were being brought into an entirely male-centric curriculum. And with very few exceptions, there has been no effort to change that. There have been efforts to add on a few women, in the cases of women in color, for instance, but there’s been no effort to explain that what we’ve been transmitting is a narrow history. A narrow, phallocentric history. And a Western one, too. Now that we’re moving into such a globalized world, how arrogant is it to teach Western history as if it is world history? As if it is universal history? How arrogant is it to show [imbalanced proportions of] white male art at the National Gallery in Washington, DC, which is a tax-funded institution? Its statistics are appalling. Really skewed. Is that the history of America? Is that the history we want young people to learn?

But that is a highly contested set of issues. Because how history is written, both in and out of art institutions, is how you shape the world. And so giving up control of that and rethinking that hasn’t happened. It’s not enough to have a few women’s studies courses. Why is it more important to study Paul Revere’s midnight ride than it is Susan B. Anthony’s 50-year effort to transform the face of America for women? How off balance is that? Men really cannot conceive of what it’s like to grow up and look on television and see that all the major sports figures are male, all the major politicians are male. If you go to an art institution, most of the art is by men. When you’re in school, most of the events you study are about men. Men’s activities lauded and repeated over and over. What about us? What about commemorating the decades-long struggle for suffrage? Why don’t we hear those stories over and over and over again. It’s almost inconceivable for men to understand what it would be like to live without that constant valorization.

One of the reasons I think people said seeing “The Dinner Party” changed their lives is because it reminded them of the complete absence that they had grown up with, that they had never even noticed until they had presence.

I think this hits on an important point. It becomes a conversation when we are adults, but when you grow up as a girl, going to a museum and seeing nudes and masculine imagery and not understanding the context of these images. We can talk about how much digital media is changing the conversation, but how do we change the conversation for a 10-year-old girl or child of color?

That’s absolutely right.

You write about this at the beginning of “The Dinner Party: Restoring Women to History,” that you encountered professors in your early studies who simply believed women had not contributed to history. Do you still encounter individuals like that?

It’s hard to believe, right? Well, a few years ago when I showed at a gallery in Santa Fe, around the time of the permanent housing of “The Dinner Party,” my gallerist flat out told me that he had been at a party and this man said -- in response to a viewing of my Hatshepsut plate, one of the four female pharaohs -- that there have never been any female pharaohs. Yes, there’s still a built in resistance because that’s what people grow up learning. They grow up learning it. And like you were saying, about not having that, how can we become empowered and claim space in the world and feel confident while feeling bereft?

I’m noticing more and more that institutions -- like MoMA and its “Designing Modern Women” exhibition -- are looking into their permanent collections and trying to find those women artists to create exhibitions that reframe history, however efficiently they end up doing that.

Let’s look at MoMA. I read the “Designing Modern Women” catalogue and I went to the show and when I walked in saw [signs for] Matisse, Monet, etc. All men. And then there was a small sign for “Designing Modern Women.” One of the things happening in major institutions like that, which are the pillars of the phallocentric narrative in art, is that they are trying to figure out how to include more women and artists of color without disturbing the existing narrative. It’s not an accident that my work is not in any of those major collections because my work would disturb those narratives.

I heard a story told to me by [a curator]. He said that whenever he brought up acquiring a woman artist, the first question was: How big is the work? And if the work was too big they wouldn’t take it. They’d only take it if it was small.

Why do you think that is?

So that it could remain minor. So you have a small Hannah Wilke and a small Louise Bourgeois. At MANA this year, the show is going to have my 32-foot-long painting and a 22-foot-long drawing. Two of my large scale works from my early career. And that is why I’m having a spread out retrospective, as opposed to one major institution. Because there is not one institution in the world that would accord 92,000 square feet to a woman artist like what was accorded to Jim Turrell last year.

There were a lot of criticisms charged against “Designing Modern Women’s” organization and the curatorial emphasis on women who collaborated with powerful men. Which reminds me of Ken Johnson’s interpretation of the exhibition. He attempted to point out that women might be naturally prone to collaboration. Which seems ridiculous. Perhaps women aren’t naturally prone to collaboration, but some women, over the years, have realized that working in groups -- composed of both men and women -- can be advantageous to one’s career.

Yes, that’s good insight.

It’s sort of remarkable, that rhetoric that persists, that all women are naturally anything.

How do we even know what we naturally are? We’ve never hardly ever had the opportunity to demonstrate it in public space, with enough of us to make a difference.

Right. Do you feel that you are part of any one community of feminist artists or feminist academics or women artists?

I was very instrumental in creating the women’s community in L.A. in the ‘70s, but a lot of things happened since then. First of all, I left the women’s workshop there, I stopped teaching because I had such a burning desire to make art. But also, as I matured, I began to understand that we had cast the dialogue incorrectly in the ‘70s, in terms of it being strictly around gender. As it played out, it turned out that not all women were our friends and not all men were our enemies. What I began to understand is that it had more to do with values.

In “Institutional Time,” I have a chapter called “What About Men?” When I went back to teaching in 1999 it was one of my goals to find out if my pedagogical methods could apply to men as well as women. And when I was working on that chapter, I went and did research on men’s participation in the feminist movement. I was completely blown away discovering that there had always been men. There were 20-30 men at the Seneca Falls Conference in 1848. I didn’t know that! There were men’s auxiliaries to the suffrage movement that marched with the women side-by-side. That history has been erased. Frederick Douglas was an ardent supporter of women, but if you read his biographies it’s hardly mentioned. If you’ve ever read anything by Emily Dickinson and the man who championed her -- Thomas Wentworth Higginson -- he was a huge supporter of women’s suffrage, and he’s never mentioned. So that history has been erased, because it’s not in the interest of male dominance to discuss the men who have stood up against phallocentric culture, who have tried to support women’s equity. So men who feel stranded feel stranded like we do, without role models.

You’ve discussed this before, that your art isn’t necessarily political art but that it’s about morals.

Morals, yes. I have a passion for justice, which was instilled in me by my father. Justice for everyone, including non-human creatures.

Which is the direction that intersectional feminism is headed in today. Justice for all. If you could give your own pocket definition of feminism to someone in conversation, what would it be. Do you have a short answer?

Yes, it would be like bell hooks. Feminism is for everybody. That’s my pocket definition! Especially for everybody who believes in the idea that every creature, human and nonhuman, has a right to live out their own lives with dignity. You know, when people say to me that we live in a post-feminist world, I wonder what world they live in. Do you live in a tiny little world of middle class America? Yeah, maybe.

There are many people who identify as “non-feminists,” who want to define it or minimize its importance. People, who don’t attempt to understand the feminist philosophy, but who can really dominate the public conversation.

It’s unbelievable. It really is. How they can dominate and manipulate the conversation.

So where’s the megaphone for feminists to shout back at them?

Well, just putting women in power isn’t sufficient. Because there are a lot of women who are not friends of women. Who are not changing the narrative, they are maintaining it, because their power depends on supporting the narrative.

That’s where statistics fail us. When people with a voice focus on the numbers of women in power, and feel as though something has been accomplished when those numbers reach 55%, without breaking down the meaning of those numbers. Out of curiosity, do you come across these types of statistical comparisons in the art education world?

In art school, even though female students outnumber males, still, in terms of tenured faculty, white males are still the norm.

My last question, which I asked you two years ago, but now that it's your 75th birthday, I'd like to ask again: What advice do you have for young artists today?

It's a real challenge now to be a real artist. First of all, the graduate schools are pumping out hundreds of thousands of artists into a tiny distribution system. Meanwhile, most of these young people, if they don't come from money, have had to take out a huge amount of student loans so they're burdened by debt. So now my advice to young artists is: Stay out of the market place. Get a job so that you can support yourself and make art when you can. At night, on the weekends, on vacation and focus on finding your own voice and forging your own vision. And only then enter the marketplace, when you're on solid ground. Because the marketplace is chewing up and spitting out young artists like detritus.

For young women, learn your history and the history of feminist art. Because so many young artists are reinventing the wheel. I see so many young women making art that came out of "Womanhouse" in the '70s. A lot of the content is the same because a lot of the issues are the same -- sexual identity, freedom, independence. When I went back to teaching I saw these women who had been told they could "have it all" and they live in a post-feminist world, and they were struggling with that. There was this performance at Indiana University with these two women -- one dressed as a clown and the other sitting on stage. The one dressed as a clown is putting balloons in the other woman's lap, one by one. One represents college. One represents friendships. Then comes another one. Relationships. Career. Marriage. Ok, now she's juggling all these balloons when the clown comes out and drops the baby. Now she's got all these balloons and she simply can't balance all six of them. She can't. Women still struggle with this concept of "having it all." It's not a post-feminist world.

All images are courtesy of "Chicago in L.A.: Judy Chicago's Early Work, 1963–74" which will be on view at the Brooklyn Museum from April 4 to September 28, 2014.

This interview has been edited and condensed.